When we’re asked to switch to explicit, systematic instruction, many teachers worry that we’ll no longer be able to tailor our teaching to the students in front of us. Calls for whole-class phonics instruction lasting 30-45 minutes, for example, summon fears that our students will be bored by concepts they already know or aren’t yet ready for. And they resurface memories of teachers stripped of our ability to differentiate instruction as we recall problematic implementation plans during No Child Left Behind.

Part of the enduring appeal of Balanced Literacy is that it acknowledges the varied needs of our students. But differentiation in Balanced Literacy classrooms includes strategies that aren’t evidence-based, such as assessments like the F&P Benchmark Assessment System (BAS) to determine leveled reading groups , coaching students on word-guessing strategies , and opportunistic phonics instruction called “word work.”

And because Guided Reading groups tend to be small, the rest of the class spends a long time waiting for instruction. Frameworks have been developed (e.g., Daily 5, Reading Workshop, literacy centers) to make the waiting time feel productive, but there’s still a real opportunity cost for each small group lesson and individual conference.

Still, many schools hold tight to their identities as Literacy Collaborative or TCRWP schools because they don’t want to lose their focus on literacy and the benefits of a staff united around a vision for instruction. But there are other, better ways to differentiate instruction in foundational skills (phonics and fluency practice) or language instruction (ELD/ESL/ESOL).

To differentiate instruction effectively, schools need a model that is:

- Based on reliable data

- Focused on evidence-based instruction

- Coordinated across a grade level or school

- Effective at meeting the needs of diverse learners

What does it take to differentiate reading instruction?

How we’re able to differentiate reading instruction depends on the size of the school, its resources, and students’ reading data, but I’ll share my school’s structure as an example.

If we can make gains, any school can.

For context, Nystrom Elementary has historically been a failing school, but after implementing a new model for literacy in 2021, we rebounded from over a year spent in distance learning, our school had higher proficiency than ever recorded before, and our student growth is now among the fastest in our district.

We have about 450 students enrolled in Transitional Kindergarten to sixth grade:

- 75% Latinx

- 20% Black/African American

- 66% English Learners

- 95% Free and reduced lunch

We do not have teachers’ aides, tutors, an interventionist, or parent volunteers to leverage, so the work of differentiation is held by our classroom teachers with the support of a literacy coach (me) and our principal.

So what does differentiation actually look like?

During Each School Day

We are a structured literacy island in a sea of Balanced Literacy. At my school, all students read, talk, and write about grade-level text for an hour or more during a block of time centered around a knowledge-building curriculum.

Our staff’s professional development focus this year is on Integrated ELD, and we are learning how to scaffold discussions and writing tasks so all students get the most out of these rich texts.

But many of our students don’t have the phonics knowledge and reading fluency necessary to read grade level texts without support, so my whole school has also banded together for differentiated instruction in foundational skills.

We have “Walk to Read,” a dedicated block of time during which students receive foundational skills instruction aligned with their needs. This is the second year of our implementation and it’s evolved quite a bit as teachers have used their experience to refine the model.

Launching Walk to Read

Last school year, our staff learned how decoding difficulties (like slow letter recognition and unfamiliar spelling patterns, etc.) impact reading rate and comprehension. Then, we dug into a phonics curriculum that provides a sequence for foundational skills instruction spanning kindergarten to fourth grade and intervention for fifth and sixth grades.

The program includes a diagnostic assessment to determine where in the lesson sequence each student should be placed for instruction. Similar to the Basic Phonics Skills Test (BPST) or CORE Phonics Survey, the phonics assessment takes only a few minutes and it allows us to see any gaps in our students’ phonics-knowledge.

| Grade | Number of Teachers | Groups at the Grade Level | Possible Placements for Students |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transitional Kindergarten | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Kindergarten | 3 | 6 | |

| First | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Second | 3 | 5 | |

| Third | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| Fourth | 2 | 4 | |

| Fifth | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Sixth | 2 | 2 |

Making groups from this data could be daunting for any individual teacher because of the range of abilities in each classroom. But grade level teams worked together to sort the data and each teacher stepped up to teach two groups:

Last year, nearly all the teams decided on the same time for Walk to Read. While this made the schedule simple, it reduced the opportunities my principal and I had to observe and model lessons. (And it made our subbing for absent teachers a logistical nightmare in a year of many COVID-related absences.)

So this year, each grade-band has a different block of time during the day, and they’ve even adjusted the amount of time they devote to Walk to Read based on the amount of direct instruction and accurate reading practice their students need according to their stage of reading development.

During Walk to Read

Each block of Walk to Read includes time to teach two groups. While in their group’s lesson, students are taught a spelling-sound pattern they are ready to apply to their reading and writing. The block also provides the amount of fluency practice necessary for students to apply their skills to reading and writing. Independent work activities vary from class to class according to students’ ability, but they tend to include some additional phonics practice, partner reading, and time for students to write about what they’ve read.

Results: Less Work, Higher Yield

| Before Walk to Read | With Walk to Read | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Impact | Component | Impact |

| 15 min whole-class lesson | Very little benefit from exposing students to phonics concepts that met the instructional needs of so few of our students. | 30 minutes of differentiated instruction per group | High-yield lessons that meet the needs of all the students in the group 12 possible group placements, plus the opportunity for a student to be in two groups if more repetitions are needed to master concepts. Each lesson includes reading and writing practice so, every day, students apply what they are taught to text with adult-feedback. |

| 10-12 min per small group | Limited opportunities for students to apply what they were taught to reading and writing because the lessons were so short. Differentiation limited to 3-4 groups if each group met every day within their own classroom | ||

| 40-45 min Independent Work | Some students benefited from the independent practice activities, but the students most in need of explicit teaching and practice with adult- feedback gained very little from the time | 30 minutes of differentiated fluency practice | Partner reading and writing practice using the stories and skills practiced in the group lesson Fluency practice and preparing for instruction is easier for teachers to manage because each is responsible for just two groups |

Time ~1 hour Lots of prep and planning required | Time ~1 hour Limited prep and planning | ||

The amount of repetition students require to master a phonics skill varies widely. For some students, introduction to a spelling pattern followed by reading and writing with it during one lesson is enough for them to master the skill. But other students require an enormous amount of repetition in order to secure connections between letters and the sounds they represent. Our groups are able to move at different paces through the content, giving students sufficient (but not unnecessary) reteaching.

For students who have mastered the phonics of their grade level, we use reading fluency and comprehension data to determine their instruction.

| Data Point | Example Instruction |

|---|---|

| At benchmark or above in comprehension |

|

| Benchmark on oral reading fluency, but lower scores in reading comprehension |

|

| Strategic intervention on oral reading fluency |

|

| Intensive intervention on oral reading fluency |

|

Monitoring Progress

For students in fluency interventions or book clubs, we monitor progress with Oral Reading Fluency (e.g., DIBELS ORF) and/or comprehension assessments (e.g., MAZE and STAR).

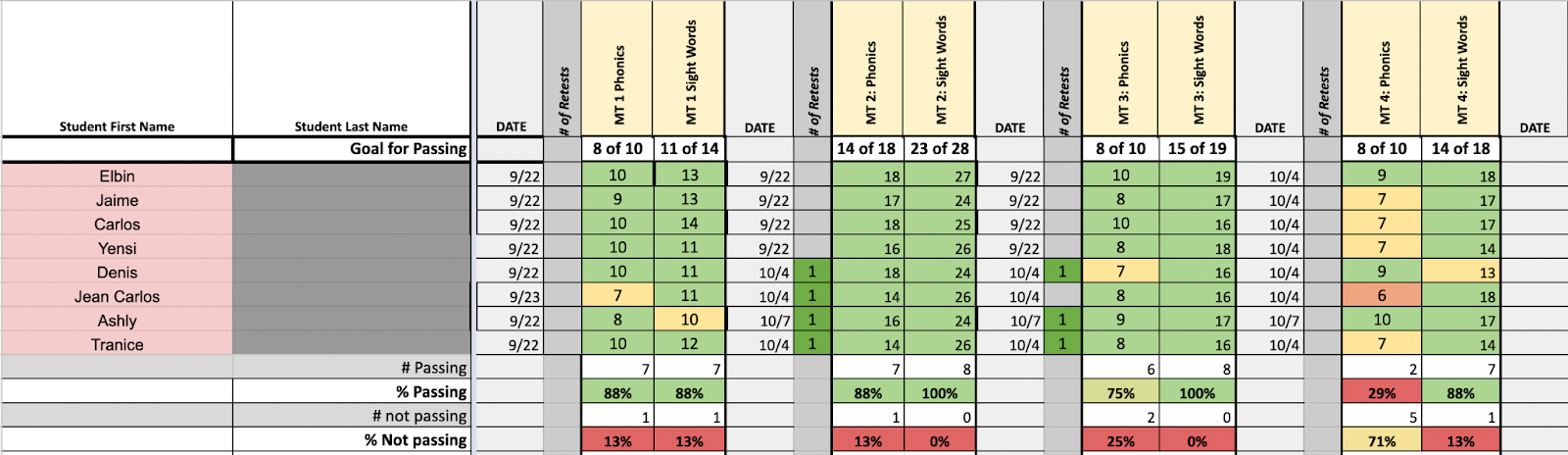

For students receiving phonics instruction, we use the curriculum-embedded tool for progress-monitoring. Every 1-2 weeks, each student receives a quick test for mastery of the content they were recently taught.

We enter the data into a shared spreadsheet and use it to determine the need for reteaching or regrouping, and to reflect on the efficacy of our instruction. Last year, our spreadsheet color-coded the individual student scores on our curriculum’s embedded criterion-referenced progress-monitoring assessment (80% on each section is the expectation for mastery).

As the year progressed, we realized that knowing each group’s pass-rate was essential to guiding instruction and coaching, so teachers worked over the summer to create an even better tracker for this year.

Now we can easily see the pass-rate for each group and also monitor the amount of reteaching and retests that it takes for each of our students to master skills.

Using the Data

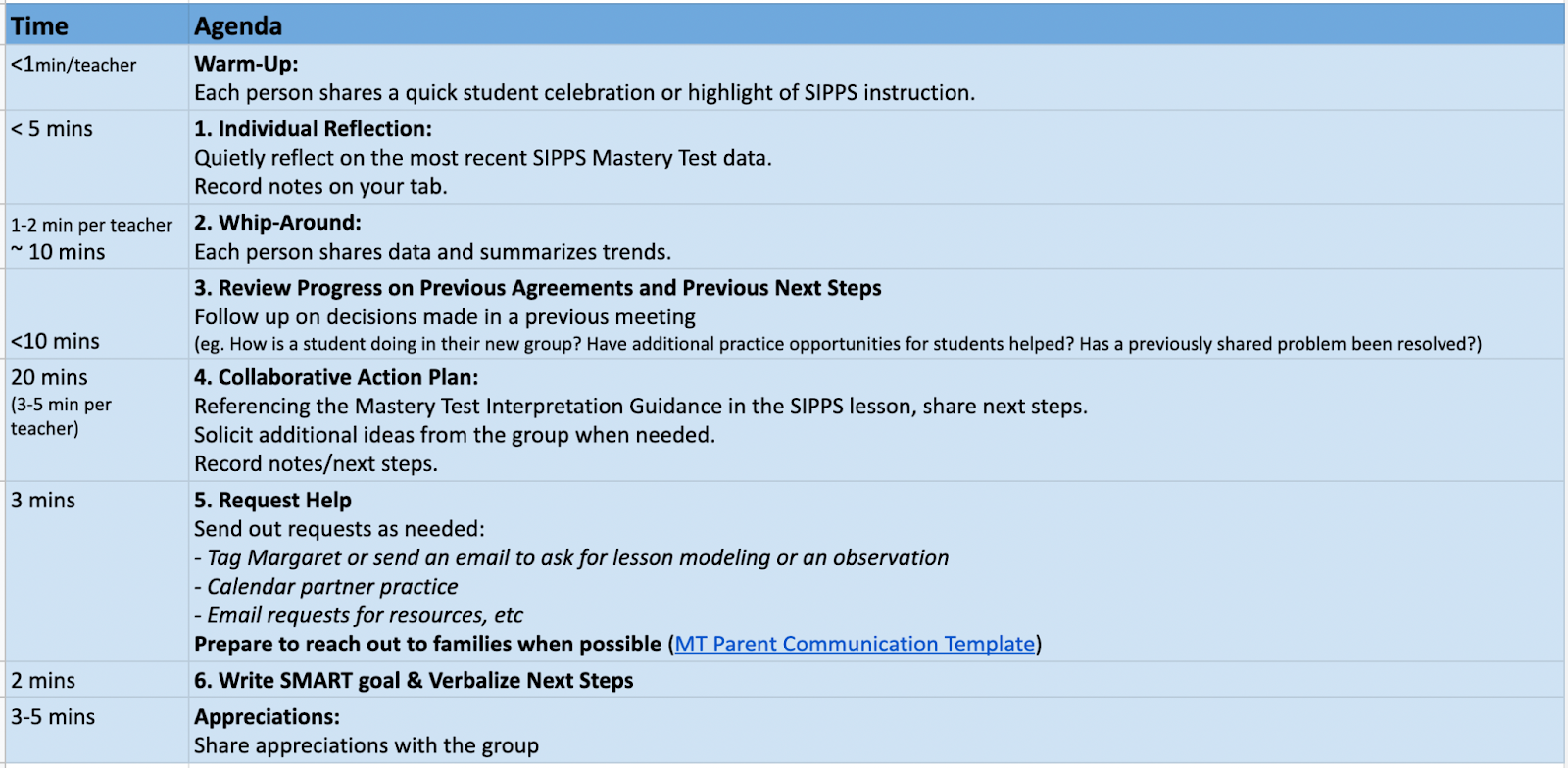

We review the data in team meetings, roughly every two weeks. These meetings are facilitated by grade-level teacher leaders, who guide the teams through the process of data analysis and ensure our school-wide norms for looking at data are upheld:

Each teacher shares the pass-rates for their group’s most recent mastery test, knowing that a high pass-rate (~75%+) is the criterion for effective Tier 1 foundational skills instruction. We discuss students’ growth and difficulties and help each other to refine instruction so that it meets the needs of our students.

Prerequisite: humility

When discussing the Walk to Read model in a staff meeting, we all laughed after reading this quote:

In its best form, walking to read allows for more targeted, more efficient, more streamlined planning, instruction and assessment monitoring. It’s a GREAT option for a highly functional staff.”

Differentiating Reading Instruction and the Walk to Read Model — Hit or Miss?

We are “a highly functional staff” as a result of years of consistent and strong leadership, a culture of instructional coaching, and ongoing work focused on student data.

We’re also a humble staff that is committed to improving instruction so we can accelerate student learning. Prior to beginning this work last year, my principal began a staff meeting by saying:

I don’t want us to complain about ‘learning loss’ this year. Our students can’t have lost anything they weren’t given. Instead, I’d rather that we focus on the unfinished teaching and how we’re going to deliver it.”

Each teacher voluntarily committed to using an evidence-based, scripted program for teaching foundational skills. We want students to experience continuity across grade levels, and we see how aligning our instruction, which in turn deepens adult collaboration, benefits our students.

I asked one teacher how she felt about teaching a scripted program for about an hour each day and she said:

I feel relieved. We’re seeing more growth than we ever have before and I know it’s because we’ve finally found something that works. I want to stick with it. I’d rather us all do something that works than see kids fail because we’re experimenting and making stuff up.”

It’s been said that “because teachers are paid so little, we compensate ourselves with autonomy,” but developing our own differentiated instructional plans becomes wearisome if that work doesn’t lead to improved student outcomes.

The Walk to Read model is energizing not only because of the teamwork necessary to coordinate instruction, but because we see exactly how each teacher contributes to the greater good of our school. We see how each teacher pitches in to meet the needs of our school’s 450 individual readers.