As the foundations of Balanced Literacy begin to crumble, the proponents of Balanced Literacy are presenting a new theory of reading, which they call the Complex View. In this reincarnation of the reading wars, the Complex View seeks to counter a well-researched alternative, The Simple View.

I was struck last month by the contrast between two articles that were published on the same day (December 5, 2019):

| The Complex View |

The Act of Reading: Instructional Foundations and Policy Guidelines |

| The Simple View |

There Is a Right Way to Teach Reading by Emily Hanford in |

The conflicting publications from December 5th exemplify a debate that is taking up teachers’ time and stymieing our collaboration.

The irony of the debate

The Simple View is supported by hundreds of studies which have shown decoding and language comprehension are critical to skilled reading. The current debate is ironic because the Simple View was originally presented in an effort to end the Reading Wars. But leaders in the Balanced Literacy community reject the balance proposed by the Simple View because it does not align with Balanced Literacy curricula.

Different instructional implications

Collaborating to build strong readers is impossible when we lack a shared understanding of what reading actually is. Instructionally, these two different explanations of reading have very different implications.

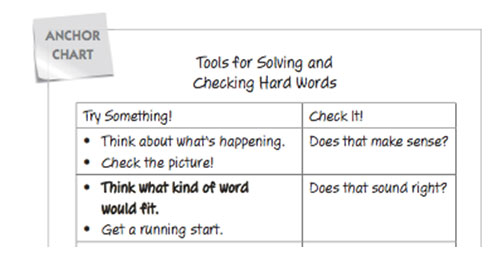

| The Complex View | With the Complex View, a teacher has many prompts from which to choose when a reader comes to a tricky word. She might reference some of the letters in the word:

Or she might ask the child to use language to compensate for difficulty with decoding:

Balanced Literacy is based on the belief that readers can attend to meaning and structure as alternatives to decoding words. Its materials are therefore incompatible with the Simple View of Reading, which asserts that if we aren’t attending to the letters on the page, we aren’t reading. |

| The Simple View | A teacher with the Simple View in mind would ask herself just two questions when a student comes to a tricky word:

|

An analogy

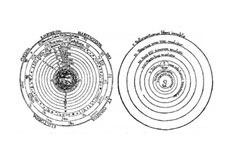

Dr. Steven Dykstra compared the opposing positions on reading to another area of science:

Complex View  | The complex view of the solar system put Earth at the center, and everything moved around us. Objects moved in different orbits of different shapes that cannot be described mathematically and had little or no relationship to each other. Mars and Jupiter, for instance, followed different rules and ways of moving just like Bobby and Susie follow different rules and ways of reading. Like the complex view of reading it relied heavily on philosophy as opposed to science, and contradicted the known science. It was very complicated. |

Simple View | The simple view says the earth goes round the sun, along with the other planets, while revolving on their axes. Like the simple view of reading, that model is not actually simple. The orbits are eccentric, not circular, and each influences the other in measurable ways. Various orbits tilt and even overlap. Earth’s own orbit and tilted axis include known wobbles that combine to produce complex variations that can trigger changes in climate, and we’re still learning more about it … |

Dykstra’s analogy reminds us that:

- Complex explanations sometimes reveal a fundamental gap in understanding.

- Science doesn’t stop with a simple explanation, but it often builds upon one.

- Not everyone can do the science necessary to discover what is or isn’t true, so we must decide whom and what to trust in order to make sense of basic phenomena.

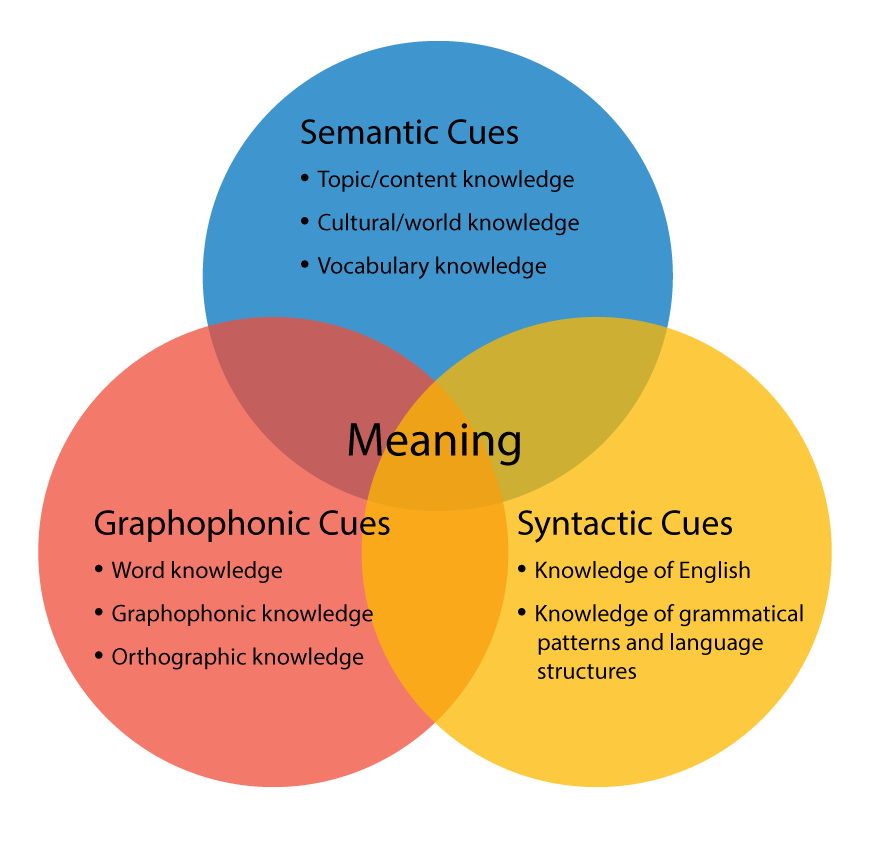

Teachers once believed that all parts of reading orbited meaning:

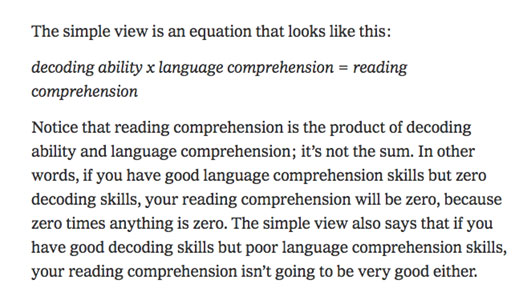

But we are now learning that a linear explanation of reading comprehension is more accurate:

Decoding x Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension

Interestingly, the simpler explanation of reading also aligns with the definition held by those outside the teaching profession:

And it makes sense with what we know about written English:

- Writing is a code developed to represent spoken language .

- Spoken English has roughly 44 phonemes.

- 26 letters, in different combinations, are used to represent the sounds of spoken language.

- Half of all English words are predictably represented by their spelling.

- Another 34% of words would only have one error if they were spelled using sounds and spelling patterns.

- So 84% of words are mostly predictable.

- Factoring in word origin and meaning, just 4% of words are truly irregular (How Spelling Supports Reading by Dr. Louisa Moats)

It seems so simple

The Simple View is clear about the roles of decoding and language comprehension — both are necessary for reading and neither alone is sufficient. Written and spoken English can be taught separately until readers are automatic in their decoding and they can translate print to spoken language by themselves.

But it’s not easy

Replacing a complex explanation with a simple one poses emotional and logistical challenges.

Emotional challenges

The Simple View cleared up confusion I had about reading, but then a rush of shame crept in.

If reading can be explained so simply, why did it take me so long to understand it?

And I thought of my students who had struggled with reading. Instruction that had once felt so right- teaching basic decoding and comprehension simultaneously- now looked so very wrong.

Why had I watered down phonics instruction and language development by using low-level, predictable texts? No wonder my students had struggled!

When our conception of reading is complex, it’s easier to accept the fact that so many students struggle to read. A clearer understanding of reading paves the way for more efficient and effective instruction. It also makes our illiteracy rates inexcusable, which triggers strong feelings in those who have worked with struggling readers.

The Simple View presents an easy-to-understand theory, but the resulting instruction is not easy.

Logistical challenges

Teachers have many data points to collect and remember:

- Which students are still developing which phonemic skills?

- What spelling patterns has each child learned?

- What instruction does each student need to become a more fluent reader?

- Which students can speak and understand sentences with multiple clauses?

- Which students require basic vocabulary instruction? And which need more advanced lessons?

And so many logistics to manage:

- How do I keep squirrelly six year olds on the carpet long enough for instruction?

- What should the other students be doing while I pull a small-group?

- Etc. etc. etc.

So now what?

Teaching reading is not easy, but every teacher wants to do it well. Effective instruction, aligned with the Simple View, can bring our literacy rates closer to those promised by reading research. This transformation requires changes in thinking and materials, but just as we’ve moved on from the earth-centric explanation of the solar system, we can leave the Complex View of reading behind. On the other side of the current reading debate is a universe worth exploring.