Thank you for writing No One Gets to Own the Term “The Science of Reading.” I am so relieved that discussion of reading science has made its way into the balanced literacy community and that you’ve added your own voice to the conversation. You’re making it safe for experienced educators to refine our practice as a result of new learning.

For many years, I was a devout reading and writing workshop teacher, so I recently seized an opportunity to become a literacy coach in a district adopting Balanced Literacy. It was a more difficult job than I expected and the experience forced me to confront all that I did not know about reading. In an effort to help teachers and kids, I dove into reading science and my world was upended.

I hope that in your learning process you’ll be willing to hear from teachers like me, who have struggled to reconcile your programs with reading research. Any changes you make to your materials will improve instruction for millions of children and the way you explain your revisions will impact professional development for teachers everywhere.

I hope you’ll read on as I share some areas in your published programs that I think could use your attention. Shining a light on a few practices is worth some discomfort if it contributes to the creation of better tools for teachers.

Three-cueing instruction

You recently wrote:

“I do not know anyone who defines his or her method for teaching reading as ‘the three cueing systems.’”

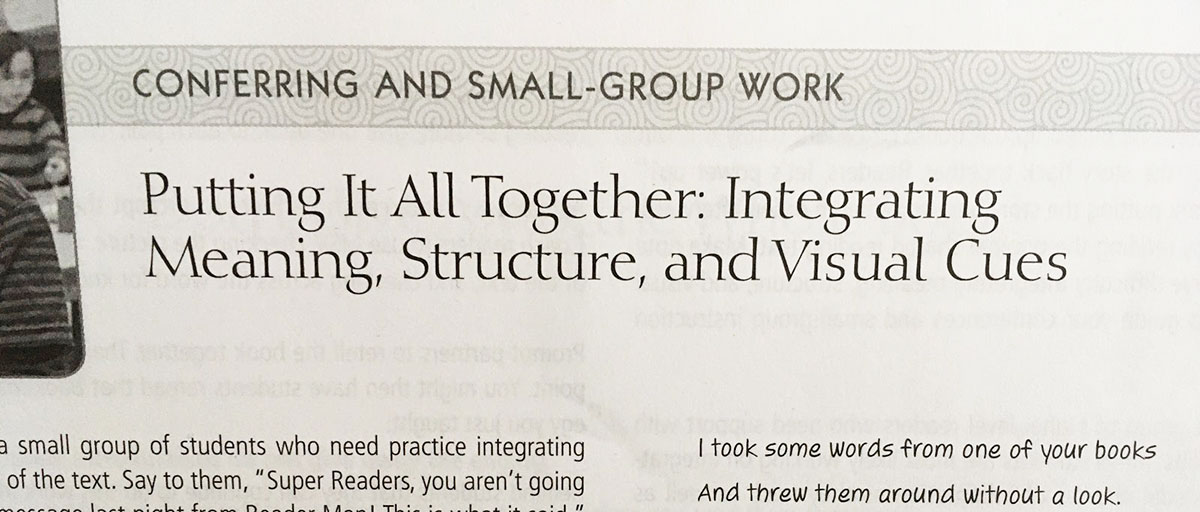

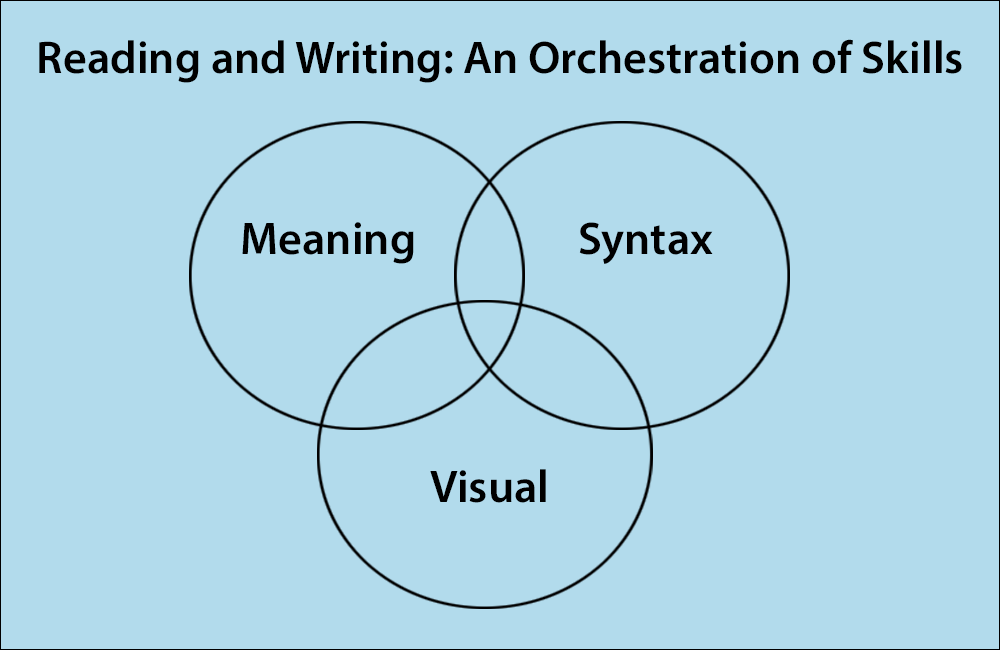

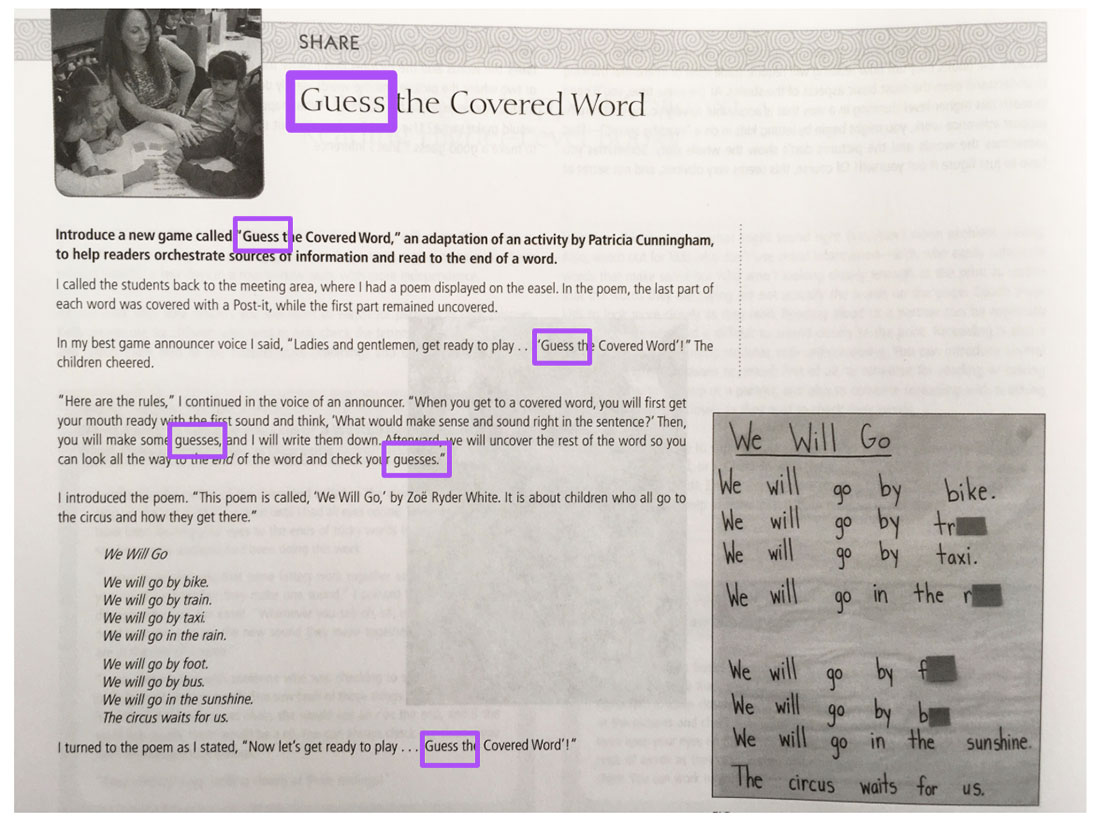

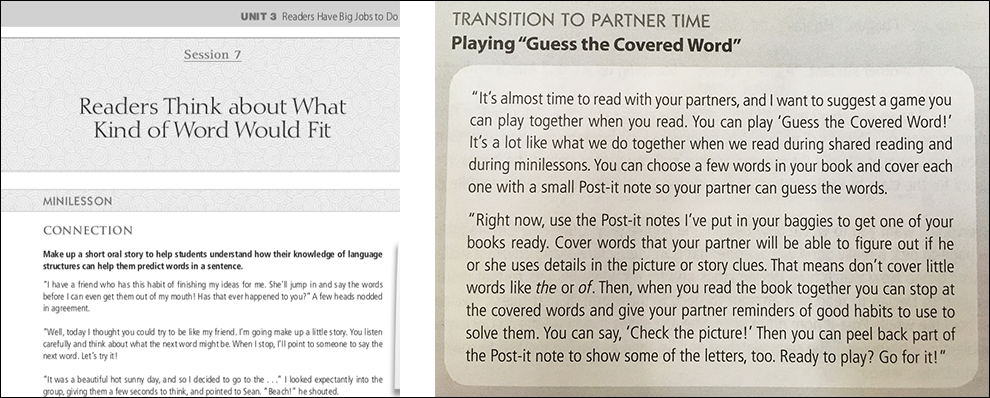

“Three cueing” is shorthand to describe instruction and assessments grounded in meaning, structural, and visual cues (“MSV”), like the lesson below from Units of Study for Teaching Reading.

You wrote recently that when a child comes to an unfamiliar word, a teacher should say:

“Hypothesize drawing on all the sources of information available to you.”

Acknowledging that the wording is challenging, you explained that some teachers might take a short-cut and say, “Guess.”

I had a chance in 2016 to attend the Teachers College Reading and Writing Program (“TCRWP”) Foundational Skills Institute. At the Institute, we discussed cueing instruction when our trainer displayed the three-cueing Venn diagram and explained the purpose behind “strengthening MSV” lessons. [Slide recreated below]

Our trainer frequently used the word “guess” to describe what good readers do. Your programs, Units of Study for Teaching Reading and Units of Study for Teaching Phonics, use that word as well.

Teachers who have told readers to guess at words do so not because we are taking shortcuts, but because of the training and materials we have received.

I was happy to read your recent words- “The ‘science of reading’ people are all-over the word guess and they aren’t wrong about that.”- and I look forward to seeing what that means for TCRWP trainings and your published materials.

I hope you’ll do more in the revision process than replace “guess” with “hypothesize.” Even if we don’t say “guess,” when we teach students to identify words using strategies other than decoding, we are approaching reading as if it were a guessing game.

“Children who routinely adopt alternative cues for reading unknown words, instead of learning to decode them, later find themselves stranded when texts become more demanding and meanings less predictable. The best route for children to become fluent and independent readers lies in securing phonics as the prime approach to decoding unfamiliar words.”

— Primary National Strategy 2006b cited by Dr. Kerry Hempenstall in The Three-cueing Model: Down for the Count?

“The three cueing systems model does not address the needs of struggling readers. It appears that the three cueing systems model simply reinforces the kinds of habits that naturally occur among children who struggle in reading. It provides no avenue for weak readers to close the gap with their same-age peers.”

— Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, Dr. David Kilpatrick

As I studied the research, I realized that parts of Units of Study teach beginning readers the habits of struggling readers and I began to advise teachers against those lessons. I hope you, too, will start guiding teachers away from MSV instruction.

Lessons in guessing are unnecessary if we refrain from giving students texts that contain words they can’t yet decode.

Leveled texts

I imagine that many advocates gave an audible sigh of relief when you said that predictable texts are “the last thing children who are dyslexic need.”

Pushing the conversation a little further, students with dyslexia are not the only ones who struggle with predictable texts. In theory, both decodable and predictable texts are temporary scaffolds to authentic books. In actuality, predictable texts become permanent reading for too many students.

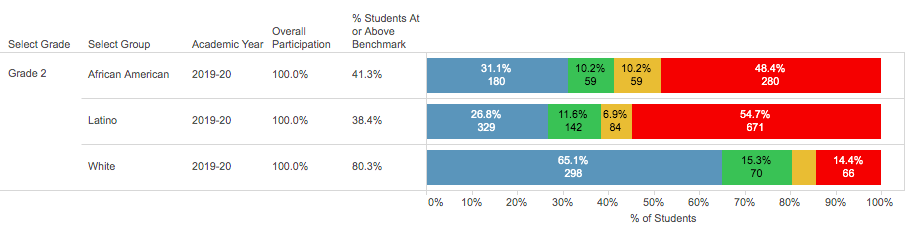

In my district, when we look at 2nd graders stuck in low-level texts, the achievement gap is glaring.

Our Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment Data:

You explain that predictable texts are helpful because students can “approximate reading,” but too many of our kids, especially kids of color, are spending valuable instructional time approximating reading. Decodable texts offer the most efficient and reliable path to authentic texts, for students with and without diagnosed learning difficulties.

Independent reading

In The Guide to the Reading Workshop, you provided the example of a child reading ten or more Level C books in a thirty-minute sitting. From an adult’s perspective, this may seem like a pleasant and productive use of time, but a child may feel differently about it.

Some struggling second grade readers will quietly flip through books during independent reading, but others quickly grow bored. More than once, I’ve seen a child throw a book bin and shout, “I hate these stupid books.” There’s no convincing an eight year old that his Level C books aren’t stupid.

Children who struggle with reading realize something many adults do not understand– they do not learn to read by reading. Desire to learn and time to practice are not sufficient for most students. They need to be taught how to read.

I began to question why we prioritize independent reading in our instructional minutes when I saw beginning and struggling readers sitting alone with books, waiting to be taught. I read many of the studies cited in Units of Study for Teaching Reading (e.g., Foorman (2006) . Where you inferred that independent reading time produces skilled readers, I read that skilled readers read a lot, and that instruction is necessary to build skill.

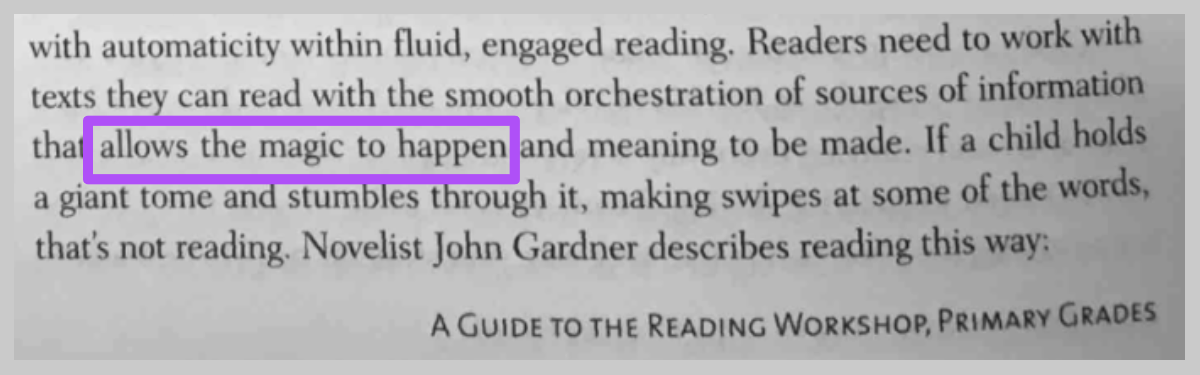

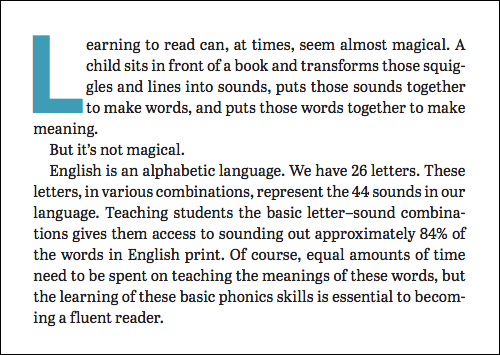

Why is this so important? Because if we shift from seeing reading as a magical process and instead see it as an unnatural skill that requires explicit instruction, the way we use instructional time changes, too.

As Wiley Blevins , whom you cited, writes:

Phonics

It’s now rare to meet a primary grade teacher who does not teach phonics and that may be due to your current message about the importance of phonics instruction.

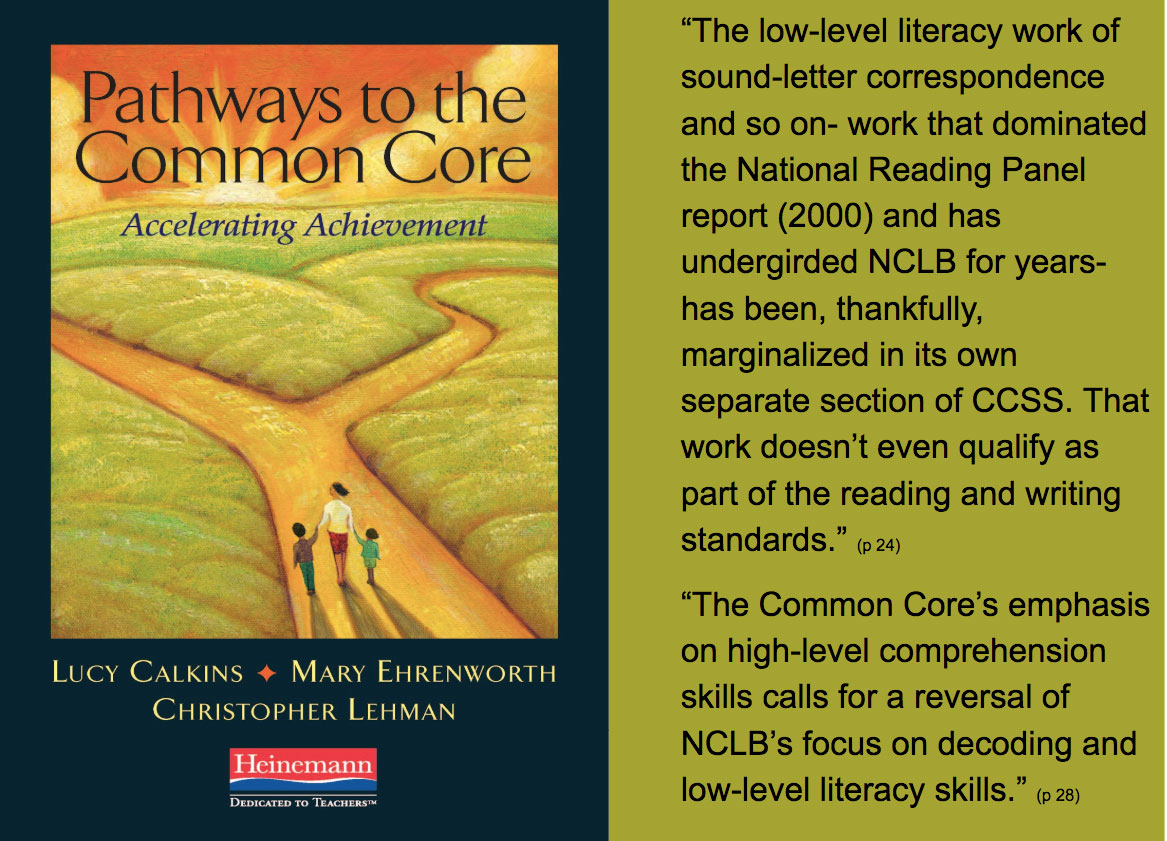

I wonder if you might be hearing “phonics-centric” conversation because people are trying to better understand your beliefs about the role of decoding in reading. My own thoughts about phonics have changed in the past few years. I’ve gone from thinking it is a small but necessary part of reading to understanding the Simple View of Reading and how decoding impacts comprehension. Perhaps people are wondering if your thinking has changed since you wrote Pathways to the Common Core.

In recent years, many schools have applied what’s been called a “phonics patch,” a layer of phonics instruction on top of cueing/MSV. The phonics patch is popular among educators who see decoding as a “low-level literacy skill,” rather than as the very thing that makes reading to oneself different from being read to. Adding phonics to the school day is a step in the right direction, but we have many more steps to go in order to align instruction with reading research.

This brings me to some difficult questions, ones I have asked myself repeatedly.

How committed are all of us to our previous thinking and to the approaches grounded in that thinking?

How willing are we to seek out and incorporate new learning?

Reading science

The divide between the research and education communities has resulted in research left on the table and classroom practices that are not as effective as they could be. Bridging the divide is where educational leaders, like you, have the power to do the greatest good for teachers and children.

New learning will likely result in new materials and trainings, but I hope that in addition to creating new work you will continue to revise what you’ve already published. Words such as “guess” are written in lesson plans that will be used across the country unless you campaign to retract them. Problematic practices (like guessing instruction and time spent with predictable texts) will continue unless you actively discourage them. I hope that you will continue to look back, reflect and revise, and that you will then look forward to all the good you can do by bringing classroom practice closer to reading science.

You have enormous influence and I look forward to seeing how you use the power of your words to guide the instruction of teachers across the country.

Sincerely,