Former Kindergarten teacher and world traveler Launa Hall is back with us at Book Life to share part five in her special guest series “Learning to Read Around the World.”

Chào mừng đến Việt Nam!

Learning to Read in Vietnam by Launa Hall

For two weeks before I walked to the little school in northern Vietnam’s mountain mist, I’d hiked around, learning something of the children’s lives. Chickens ambled in every yard, water buffalo grazed nearby, and rangy dogs lay at the sunny edge of the road. Moms hung black hoses for a trickling water supply from nearby waterfalls, and dads with machetes returned from the deeply green hillsides with lengths of bamboo. Whole families balanced on a single motorbike, tiny babies strapped onto their parents’ backs.

At left: Overlooking the school in a Hmong village high above Sapa, Vietnam. At right: A mother in traditional Hmong headcovering, with her young son and baby, leaving the village grocery store on her motorbike.

Now, at just before 8 a.m., the last of the motorbikes zip in, delivering kids to school as I walk through the entrance’s red archway. An enormous black pig snorts on the other side of the fence, watching the busy, flowerpot-laden courtyard. This government-run school is for two- through six-year-olds; their older siblings go to elementary and secondary school a few miles away.

The school’s cliffside assembly area. The sign overhead shows an image of Ho Chi Minh embracing a child, and the accompanying quote translates to “The school is home, the teacher is mother, the students are children.”

Parents supervise as their children place their shoes on tidy racks and slip on matching plastic sandals before entering the clean-swept classrooms. Other parents are tending the gardens. In fact, evidence of parent involvement is everywhere, such as the whimsically hand-painted animals, trees, and fairytale characters winding around the walls and stairways.

The hand-painted sign in the play yard translates to “Fairytale Garden.”

I am ushered to the Kindergarten-age classroom, where a lovely, smartly dressed teacher welcomes me. She and most of the other sophisticated young teachers are from Hanoi and were formally trained there. They have volunteered for this remote mountain assignment to help bring education –– starting with the Vietnamese language –– to this Hmong community, part of Vietnam’s rich patchwork of 54 distinct ethnic groups.

Hmong people have lived in the mountains of Vietnam and neighboring countries, speaking the Hmong language and practicing distinct cultivation techniques, for thousands of years. Despite the devastation of the Vietnam War years, well over a million Hmong are here today. There’s a strong spirit of resilience and entrepreneurial spirit in the mountains, a heritage of facing tough mountain conditions for generations. Parents know, though, that opportunities for their kids beyond the village will be in the national language of Vietnamese, and they send their kids to school as much as they are able.

I watch the teacher start the day. Just above her head hangs a black-and-white photo of a paternal figure holding a small child in his arms; he’s the country’s former president, education reformer, and national role model of communist ideals, Ho Chi Minh. The children, sitting in their neat horseshoe of plastic green chairs, follow their teacher in a short recitation. She is both smiling and firmly all business. It’s time to work. The children know the poem by heart.

They move on to repeating vocabulary words in unison from large picture cards: xe tải (truck), xe lửa (train), ô tô (car), and so on. This, as I see again and again during my visit, is the clear emphasis of instruction here: learning Vietnamese vocabulary, both in isolation (such as with the picture cards) and also through embedded experience during their school day.

I look around the room. Neat rows of the national curriculum workbooks line one shelf. Nearby, musical instruments await beside perfectly stacked blocks. In the corner classroom library, a few precious books are displayed in handmade frames. A small chart by the teacher’s desk lists family names and whether they’ve paid a particular fee for the school year; the amount is 90,000 dong, or $3.44.

The sign translates to “Corner Storybooks.”

After one more repetition of the transportation vocabulary, the teacher gives me the international gesture of “over to you!” and I find 24 pairs of expectant eyes turned to me. I start to say that I’m only observing, but I stop myself, understanding that all adults who come through the red archway are expected to participate. Here, everyone contributes.

Remembering what my language-learning Kindergarten students loved on the other side of the planet, I invite these little ones to a rousing sing-along of motion songs. I start with “Wheels on the Bus” since it fits the theme of their vocabulary lesson; they honk their imaginary horns and bump up and down with enthusiasm. We sing “Head and Shoulders, Knees and Toes,” and “Itsy-Bitsy Spider.” We don’t have a single word in common, but with gestures and a few hastily drawn vocabulary words, we do just fine.

Children enjoying a motion song. Note their matching purple sandals, worn only in the classroom. These students don’t yet have school uniforms; their older siblings in elementary and secondary school wear white shirts with bright red kerchiefs. These days, those older students have the option to study English.

As I leave the classroom to visit another, they are guided back to their little chairs, where they are gently shown not only to sit but to sit a certain way, both feet on the floor. Lessons in Vietnamese vocabulary are important, and perhaps equally so are lessons in orderliness. They do get breaks, though –– later a teacher turns to the large screen at the front of her classroom that had been dark until then. She turns on a children’s song, and with surprising volume and gusto, the kids sing along, taking turns at the front of the room.

Over the next few hours I see teachers bring out little folding tables and boxes of crayons for the workbooks. Published by a government-owned company, the books work systematically through the Vietnamese alphabet. Vietnamese has been a written language (in combinations of Chinese characters and symbols endemic to Vietnam) for more than a thousand years, with a rich literary tradition stretching back centuries.

Each child is assigned a cup marked with a letter of the alphabet. This not only keeps the water station perfectly tidy, but helps children build familiarity with the letters.

But today’s writing system (an adapted Latin alphabet with 12 vowels and 17 consonants) dates from only the 17th century. It came into universal use even later, in a wave of cultural and educational reforms following the French colonial period. Vietnam’s move to a standardized, alphabetic writing system was part of a plan to foster modernization and economic growth, promising all of Vietnam’s people a speedy road to literacy through phonetic decoding.

This largely worked. Literacy rates have soared upward along with Vietnam’s spectacular economic growth. Yet this promise is harder to obtain for children who grow up speaking one of the ethnic minority languages in Vietnam. Plus, the villages where those languages are spoken –– mountainous and remote — are exactly where money’s so tight that even modest school fees can be a barrier. In my nearby homestay, as one example, I learned that the Hmong teenager who worked in the kitchen had never been to school at all.

Other troubles locals face include instances of bride kidnapping, an old tradition in Hmong communities that still occasionally occurs. Additionally, human trafficking persists from this economically depressed region across the nearby border with China, causing the disappearance of many hundreds of young women and girls each year.

I learned another story of economic desperation while hiking nearby Fansipan Mountain. Our guide told us that he eventually met a teacher who helped him become a success in the tourism sector, but when he was barely a teenager, destitute and on his own, he slipped across the river into China to work in an illegal logging operation. He was too young for the brutally physical work, but he was stuck. Many months passed before he managed to escape back home to Vietnam.

Pondering these stories, I watched the little children at school, sitting two to a tiny table, heads bent in quiet concentration over their workbooks, learning the Vietnamese letters.

When I leave a few hours later, the aroma of freshly cooked rice wafts from the cafeteria downstairs. I walk to a neighborhood cafe to think about what I’d seen: well-fed, well-cared-for children. They are learning from devoted, hardworking teachers. The parents are actively involved. Their classrooms are outfitted with many more resources than I anticipated in a mountain village. The amount of sitting still and speaking in unison seemed like a lot to me, but I was beginning to understand the motivation behind it: the sense of urgency, the drumbeat of approaching economic pressures on the children of this community. Education is deeply important now, while they’re small.

As I wait for a coffee, a little girl approaches to sell me a trinket, a bracelet of knotted colored yarn. She is no more than two or three years older than the children I sang with that morning.

Truly, the teachers must feel, there is no time to lose.

Features of the national reading curriculum in Vietnam:

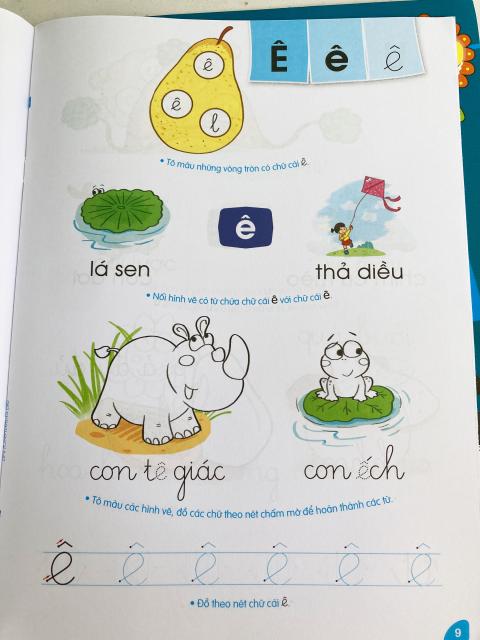

- The workbooks build from letter recognition, to practice printing letters, to cursive. The earliest book asks children to color images that contain the target letter, accompanied by a capital of that letter at the top of the page. The intermediate workbook gives children practice printing letters –– a new letter on each page. The final workbook does the same, but in cursive.

- They start young. State-run preschool is available beginning at 2 years old. The first workbook of the national reading curriculum is introduced at 3 or 4 years old. Printing is introduced at 4 or 5 years old, and cursive at 5 or 6.

- The workbooks introduce the vowels first (treating vowels with diacritical marks as separate letters, for a total of 12 vowels), then the 17 consonants.

- It’s not meant to be used in isolation. Since the workbooks focus on recognizing and writing letters, it’s up to teachers to teach letter sounds, then combine letters into words to give children practice decoding and making meaning from their letter knowledge.

A page from the cursive practice workbook in the national curriculum, meant for 5- and 6-year-olds. The inclusion of a rhinoceros is poignant; Vietnam was once home to roaming Javan rhinos, but the last living individual in Vietnam was killed for its horn in 2010. Today, there is a robust national campaign — starting with the youngest children — to protect the remaining rhinos in the world and end the Vietnamese market for rhino horn powder, a traditional medicine.

Take-aways from teaching reading in Vietnam

- Parents are the heart of a school. The little school I visited was welcoming, warm, teeming with beautiful plants and paintings, and kids arriving on time as a direct result of parents. The teachers made parents feel invited in and important to the school’s success. Even if the parents didn’t have the chance to go to school themselves, they were involved now, changing the narrative for their own children.

- Books are precious. I had many hundreds of books in my classroom library in the U.S., and I took my students to our school library with many thousands more. It can be easy to forget what an incredible gift that is, to have so many books for our students. The Vietnamese-language books in the school I visited are harder to come by, and they are treated as the great treasures that they are.

- Teachers are doing tremendously important work. I had a clear reminder in this mountain village: teachers create opportunities and lasting change in the lives of children and their communities. Their work might be hidden in mountain mist and might not be noticeable for years. But the quiet, quotidian dedication of teachers, here and everywhere, is the work of heroes.

Resources

- Launa at Large

- Launa Hall’s Field Trip Notebook

- Reading Tips for Parents in Vietnamese and Hmong

- Helping Second-Language Families