After her visit to South Korea, former Kindergarten teacher and world traveler Launa Hall offers us a look at the fascinating education culture she found in Seoul in part six of “Learning to Read Around the World,” her special guest series for Book Life.

서울에 오신 것을 환영합니다

Learning to Read in South Korea by Launa Hall

Like many Americans, I’d heard a lot about South Korean education: the long study hours, the pressure on students, and the internationally chart-topping scores. So when I entered an unassuming public elementary school building in the heart of Seoul one rainy afternoon, it felt like entering a space at least as significant as Seoul’s elegantly modernistic City Hall. What does a school feel like in a culture so highly focused on education? Would the pressure I’d heard about in the higher grades be evident at the elementary level, too? What would all this mean for how little kids are taught to read?

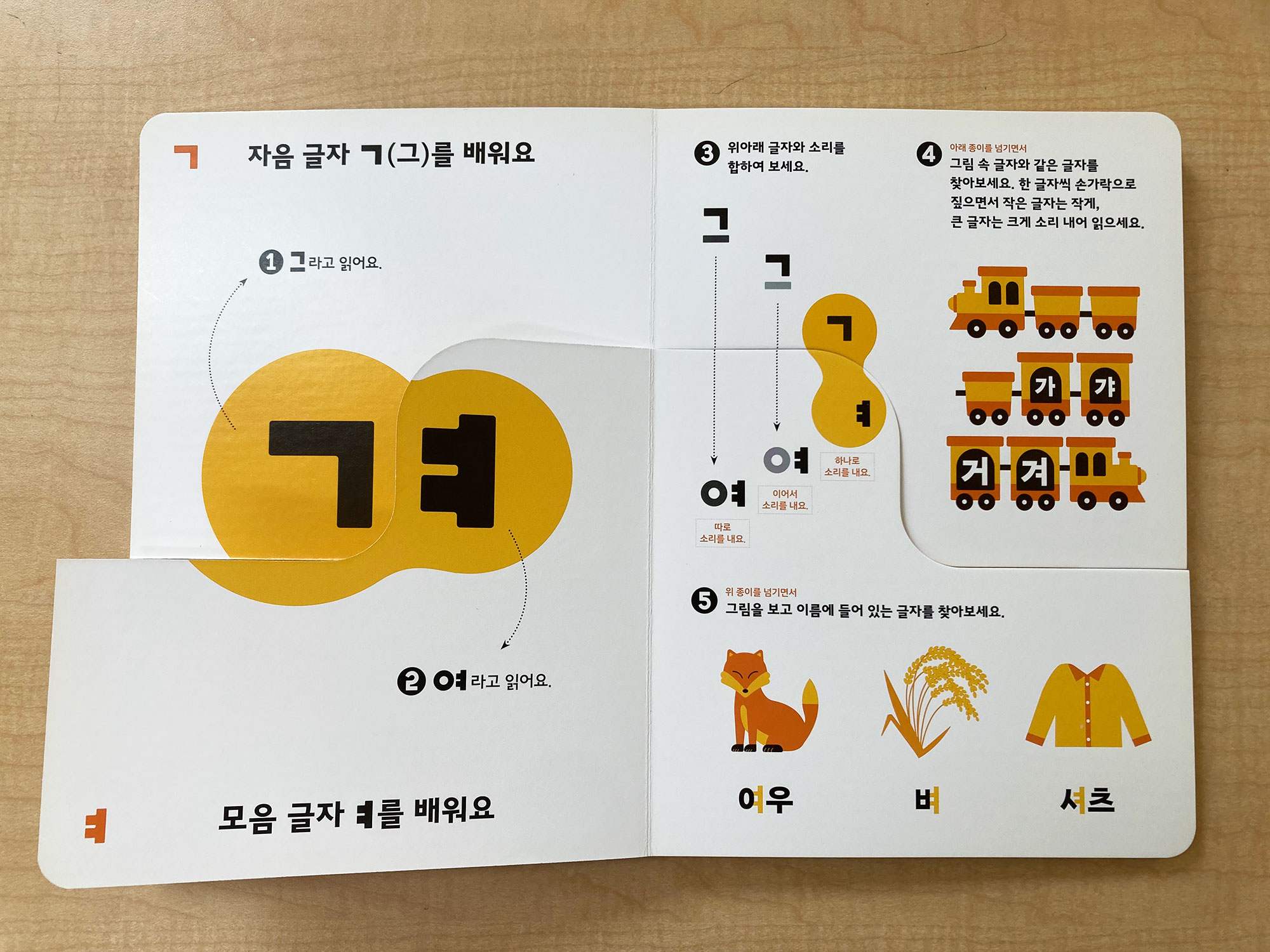

Before this school visit, I met with two parents to ask their thoughts on South Korean education. In short, I wanted to know how early the pressure starts. These moms — both with well-paid office jobs in central Seoul — started by discussing the three years of government-funded early childhood education. They described lots of exploration and creative play. Kids ages three to six are exposed to literacy through pictures, songs, and toys in the shapes of the Hangeul letters, so their early experience of their writing system is tactile, not memorized. While many children start reading in those years, they told me that formal reading instruction begins at age seven, in first grade.

An introduction to Hangeul, demonstrating with clever flaps how phonemic symbols fit together in syllabic building blocks.

But elementary school? Are engaging teaching methods found beyond Kindergarten? “More than there used to be,” the parents told me, with perhaps some ambivalence. One of the parents shared that she thinks elementary school should be harder. “Elementary school has only quizzes, not tests,” she explained, which she feels leaves kids unprepared for upcoming test-heavy middle and high school. When I asked if there is too much pressure on school kids, they told me something I heard many times while visiting South Korea: the country is relatively small with few natural resources, so their greatest resource lies in the intelligence and resourcefulness of their people, accessed through education.

Indeed, South Korean parents think a lot about education. I had wondered how early school pressures begin, and the answer, at least for these parents, is perhaps not early enough.

Would this also be the case with the small percentage of parents who opt out of the South Korean education system? To find out, I met with Diahn, a veteran Kindergarten teacher from the U.S. who teaches in a long-established international school not far from Seoul’s upscale Gangnam district. It’s staffed for small class sizes and emphasizes projects and class discussions. They aim for balance — enough work to be rigorous but not so much that the kids have no free time. In Diahn’s Kindergarten class, the reading instruction was solidly anchored in evidence-based phonics instruction and included time every day for read-alouds, songs, and engaging literacy activities.

I could clearly see why a parent with the resources might choose this school, but I wondered about the effects of a separate education path. Once parents choose it, they’re committed; the differences are great enough that it’s rare for children to move back into the public education system once they’ve left it, including college. Kids at this school will most likely apply to universities outside South Korea.

Diahn introduced me to two successful young professionals with two children at the school. For these parents, their school decision was as much about their kids’ overall experience as about English immersion. “It’s a more well-rounded education,” they said. In their perception, top students in South Korea tend toward “careers as doctors” or other fields that reward a great deal of memorization, but not toward innovative pursuits. Perhaps that stems from too much rote memorization in South Korean schools, they said, and they wanted something different for their children.

Soon after this conversation, I met a talented young interpreter who was also one of the few to attend an alternate school in Seoul. He was just beginning a career that depended on his English fluency and would take him far from home. He shrugged when I asked a question about the infamous cram schools, called hagwons, that high school students attend until late at night. “I don’t really know because I didn’t go to any,” he smiled, and I sensed a hint of wistfulness in his reply. His journey was something altogether different.

But like every South Korean I asked, he answered enthusiastically when I asked about Hangeul, the Korean writing system that is deeply fused with Korean identity. In the mid-fifteenth century, King Sejong devised a new, phonetic script in a bid to bring a better life through literacy to each of his subjects, rich and poor alike. It absolutely worked, albeit a few centuries later; the Korean literate elite were slow to move away from the old writing system incorporating Chinese characters. But Hangeul grew in general usage until it was finally adopted for official documents in 1894.

The Hangeul Museum in Seoul. The building itself evokes the classic syllable block on which the script is based.

I learned more at Seoul’s superb Hangeul Museum, an ode to Korean language and literacy. One of King Sejong’s design principles was to shape the letters to visually reflect tongue and mouth positions; kids to this day are taught this, a built-in mnemonic for sound-to-symbol connections.

On display is the first Hangeul primer for children, printed in 1895. Other displays explained the gradual standardization in fonts and directionality (it is now universally written left to right), allowing for even greater legibility and accessibility. The government has periodically updated spelling norms to keep up with subtle changes in pronunciation and usage, with the latest update issued in 2017.

All this means that today’s schoolchildren have inherited a highly regular, decodable, and consistent writing system. Add to this a robust, government-funded school system (including three years in early childhood) and a cultural focus on education, and the result might be an ideal environment to learn to read and write.

Now, from a busy street in Seoul, I walked into an ordinary public elementary school to see these cultural forces at work.

A public elementary school entrance in Seoul. The sign says “Haeoreum Hall,” named after a flowering plant commonly grown in South Korea.

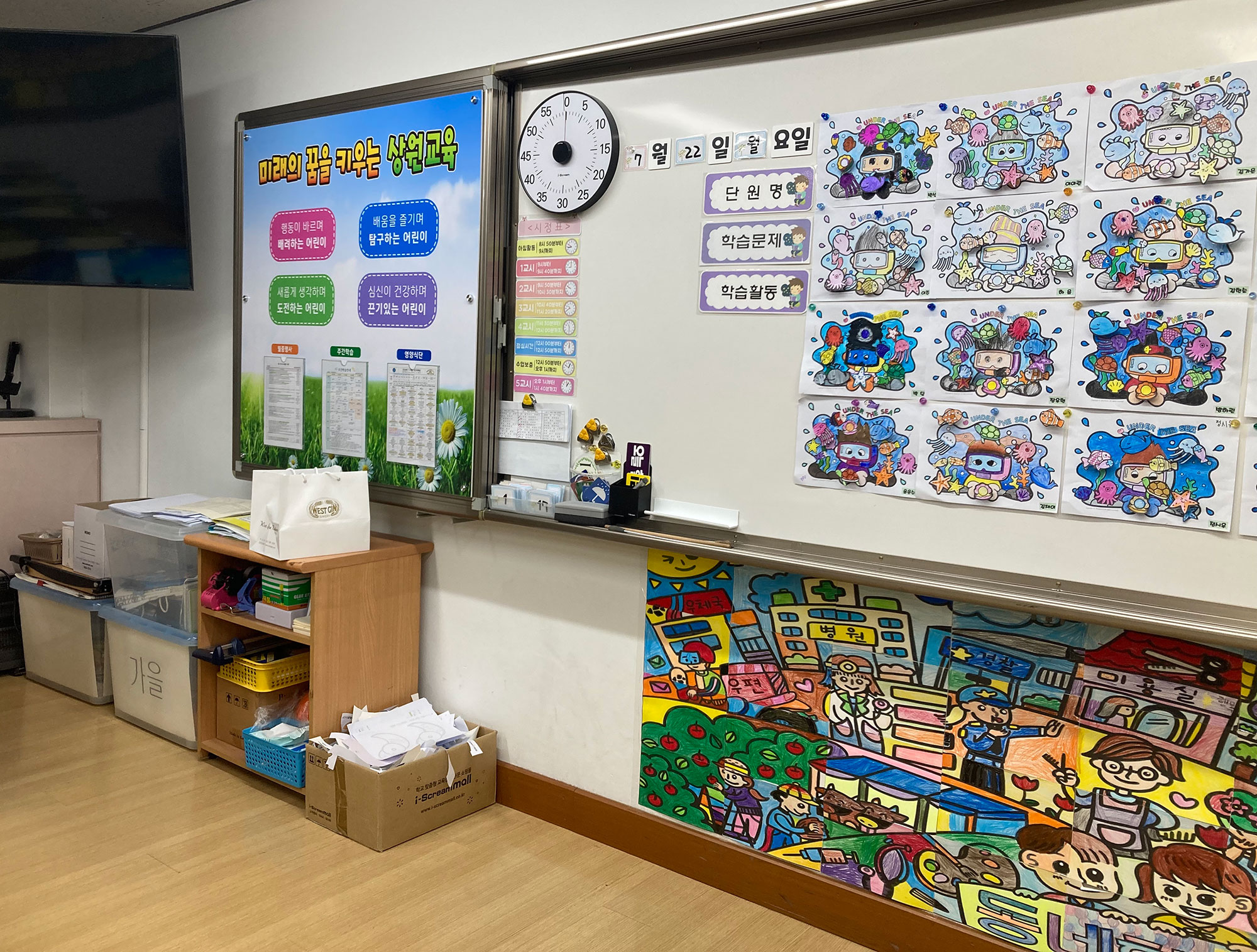

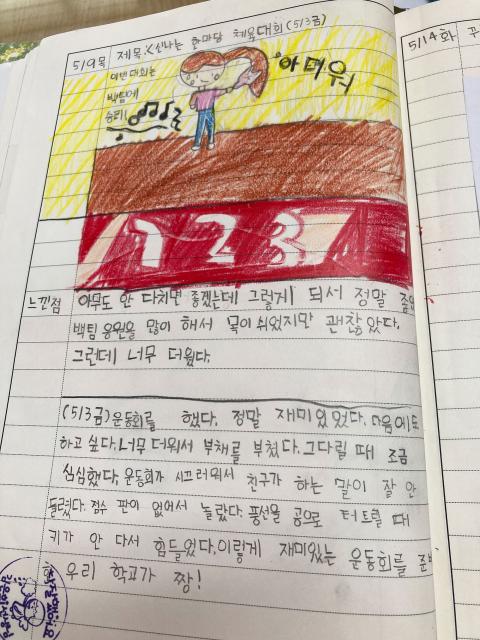

It was spotlessly clean. Children’s work was the centerpiece, hanging in several locations in each classroom, always in tidy rows that mirrored the tidy rows of desks and supplies. With children’s work at the front of the room beneath a framed South Korean flag, the tech equipment (a screen installed in the corner) played a much smaller role. There weren’t any issued tablets or laptops; in this highly tech-savvy country, children use paper and pencil to read, write, and do math.

A few teachers at the end of their school day warmly welcomed me, offered tea in the teacher’s lounge, and then we sat down together to talk. At their request I’d sent questions in advance, and they had translated and prepared answers for each one. In the course of this project I’ve now visited schools and spoken with teachers in over a dozen countries, and the poised, professional teachers at this school stand out for how thorough they were in their responses and how generous they were with their time.

An elementary school classroom in Seoul.

A theme emerged almost immediately; teachers here are well aware of issues with overwork and student stress, and they strive to bring creativity and spontaneity into the elementary classroom. While they follow the national standards closely, they look for ways to infuse it with high interest activities that don’t rely on rote memorization. One teacher makes booklets to expose students to “journalistic styles” while they are learning to read. They told me that the elementary school day has more latitude for fun and freedom than in later school years. Yes, parents send elementary kids to hagwons after school, but most academic hagwons come later. For these ages, they tend to be for sports and music.

Each day’s literacy block is organized “to reach the five senses,” they told me, and give practice in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. They showed me examples of children’s work and explained that teaching clear and accurate printing is a big priority. On Hangeul Day (October 9th each year), the whole school makes t-shirts and does building activities together to celebrate their shared literary heritage.

A child’s free writing on a topic of her choice. She writes about how hot it was on her school’s sports day and how she cheered until her throat was sore.

They estimated that about 90% of children can decode as they enter first grade. The reading curriculum used to assume students had basic decoding skills from the start, but recently that changed; now, the first eight weeks of first grade are devoted to covering Hangeul letters, their sounds, and their positions in the syllable blocks to ensure every child has a solid foundation. The teachers felt this was a good adjustment as it decreased pressure on parents and kids when they know that first grade will cover basic decoding.

As I was leaving the elementary school, I reflected that it wasn’t that long ago — within older South Koreans’ living memory — when this was among the world’s poorest countries. Today, it has a literacy rate of nearly 99% and one of the most robust global economies. Academic excellence is a national project, often translating into a lot of pressure on each child to excel.

But the surprise South Korean education held for me is a sincere effort to keep the demands under control for elementary students. The teachers I spoke with strive to keep the learning fun. They give them opportunities to be creative, and time to just be kids.

Features of South Korean reading curriculum:

- First grade texts cover basic decoding in detail to ensure all children have foundational skills before moving onto more complex reading and writing tasks.

- Learning to print clearly and accurately is an integral part of learning to read.

- Children are frequently asked to write their opinions on books they’ve read in class to build their reading comprehension skills.

Takeaways from teaching reading in South Korea

- Use books, paper, and pencils. They are still excellent learning tools, and growing research shows that developing handwriting aids literacy. While assistive technology for children with specific learning needs is an informed use of technology, blanket usage of classroom technology isn’t a requirement to teach children to read. The public school I visited in Seoul was low tech and getting great results.

- Teach the design behind the writing system. While the English writing system evolved over more centuries and hasn’t had centralized updates like Hangeul, it still has a great deal of underlying logic to its spelling that learners need to know. Teaching kids the etymology of words — the why behind the spelling — can help children remember the spelling, decode and encode accurately, and build fluency, because spelling supports reading.

- Communicate joy in our letters. Community pride goes a long way. In the U.S. we don’t have a national museum or a national day to celebrate our writing system, but schools could capture that motivating spirit by celebrating a schoolwide or even grade level Alphabet Day.

Resources

- Launa at Large

- Launa Hall’s Field Trip Notebook

- Reading Tips for Parents in Korean

- Explore Korea with Picture Books