Key Information

Focus

When To Use This Strategy

Appropriate Group Size

What is the question-answer relationship strategy?

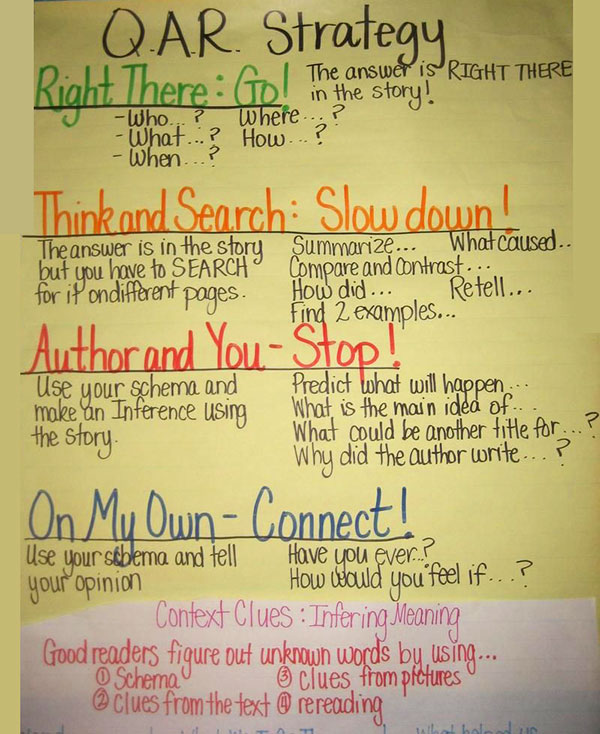

The question-answer relationship (QAR) strategy helps students understand the different types of questions. By learning that the answers to some questions are “Right There” in the text, that some answers require a reader to “Think and Search,” and that some answers can only be answered “On My Own,” students recognize that they must first consider the question before developing an answer.

Why use the question-answer relationship strategy?

- It can improve students’ reading comprehension.

- It teaches students how to ask questions about their reading, a cognitive strategy skilled readers use.

- It helps them find the answers to their questions, whether it means locating a specific fact, drawing an inference, or connecting the reading to their own experience.

- It inspires students to think creatively and work cooperatively while challenging them to use higher-level thinking skills.

How to use the question-answer relationship strategy

1. Explain to students that there are many questions readers can ask about their reading and that one way to find the answer is to think about what kind of question it is. Define the four types of questions and give an example.

- Right There Questions: These are literal questions whose answers can be found in the text. Often the words used in the question are the same words found in the text.

- Think and Search Questions: These ask readers to collect information from more than one part of the text and put it together to answer the question.

- Author and You: These questions are based on information found in the text but ask the reader to relate the question to their own experience. Although the answer does not lie directly in the text, the student must have read it in order to answer the question.

- On My Own: These questions do not require the students to have read the passage. Readers rely on their background or prior knowledge to answer the question.

2. Read a short passage aloud to your students.

3. Have questions of different types prepared to ask about the passage. When you have finished reading, read each question aloud and model how you decide which type of question you have been asked to answer.

4. Show students how find information to answer the question (e.g., in the text or from your own experiences).

Watch a lesson (small group, 5th grade)

The teacher introduces 5th grade students to the QAR strategy. The teacher guides students through the process of deciding where and how they found the answer to a series of questions. At the end of the lesson, the teacher summarizes the four types of questions and sets them up for doing this again with their teacher. (See aligned lesson from CORE )

Watch a lesson (whole class, grades 5–6)

The teacher introduces the QAR strategy and explains the four question types, distinguishing between using prior knowledge and using information from the text, and guides the students through determining question types.

Watch a lesson (whole class)

In this variation of QAR, the students generate questions about Smoky Night, a whole-class read-aloud. The teacher guides them through determining where and how they found the answer using a graphic organizer.

Collect resources

Differentiate instruction

For second language learners, students of varying reading skill, and younger learners

- Have students work in pairs or small groups to form questions about the text, find the answers, categorize their questions, and share with the whole class.

- Do a whole-class QAR activity and have the students write down the questions and answers on their own QAR templates as you write them on the board.

- Use a big book or projector to enlarge the text and annotate it so the students can follow along as you think aloud about the reading.

Extend the learning

Language Arts

In this lesson plan, students use the QAR strategy for a study of the book Story of Ruby Bridges by Robert Coles.

See this QAR template for the study of Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor

Math

In this comprehension lesson , students apply the question–answer relationship strategy to word problems that refer to data displayed in a table.

See the research that supports this strategy

Fordham, N. W. (2006). Crafting questions that address comprehension strategies in content reading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49, 390-396.

Liang, L. A., Watkins, N. M., Graves, M. F., & Hosp, J. (2010). Postreading questioning and middle school students’ understanding of literature. Reading Psychology, 31, 347-364.

Raphael, T.E., & Au, K.H. (2005). QAR: Enhancing comprehension and test taking across grades and content areas. The Reading Teacher, 59, 206-221.

Wilson, N. S., & Smetana, L. (2011). Questioning as thinking: A metacognitive framework to improve comprehension of expository text. Literacy, 45, 84-90.

Children’s books to use with this strategy

Pale Male: Citizen Hawk of New York City

How to Heal a Broken Wing