Context of writing

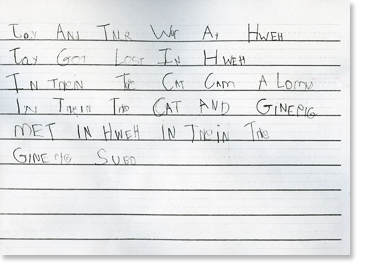

A first grade girl wrote this story. After reading William Steig’s Amos and Boris, students were prompted to write a story with an unlikely friendship between two animal characters. This is an unfinished piece; the author added more to the story after this sample was gathered.

What is this child able to do as a writer?

- She has ideas for a story — a setting of Hawaii, several characters, and a problem (‘Jay got lost in Hweh’).

- The student has written the story in a chronological sequence that makes sense. She is starting to create a stand-alone text that expresses a clear message without relying on a picture.

- The clear spacing between words demonstrates a solid concept of word.

- Spelling is correct for most words that can be phonetically sounded out.

What does this child need to learn next?

This story’s ending doesn’t fit with the rest of the story. The author could use a story map graphic organizer to plan her story first so that she has a sense of how the story will develop before she writes.

In addition to the story map, whole- or small-group lessons on story structure and prewriting brainstorming can help this young writer think about each part of the story, making sure it all makes sense.

The author tries to use transitional words (“In thein” for And then) to signal sequence but she relies on the same transitional words over and over again. She may need a list of other transition words to choose from. A transition word chart could be developed during a mini-lesson or conference where the class looks at other texts to see other words authors use to show sequence. Once created, the chart could then be reproduced in a smaller version so that the students could keep the ideas they generated in their own writing folder.