Schools all over the country are changing how reading is taught and they face two big questions:

- What curriculum will we use?

- How will we implement it?

Decisions about what will be taught, when, and for how many minutes will determine the daily experience of students, and how much they’ll learn in school. Instructional time is limited, so building classroom schedules requires a series of choices that ultimately reflect our values.

Looking back at my old schedules, I can see how my understanding of effective reading instruction has evolved. I see similar change unfolding across the country, and this makes me feel excited but also deeply worried.

Balanced literacy schedules

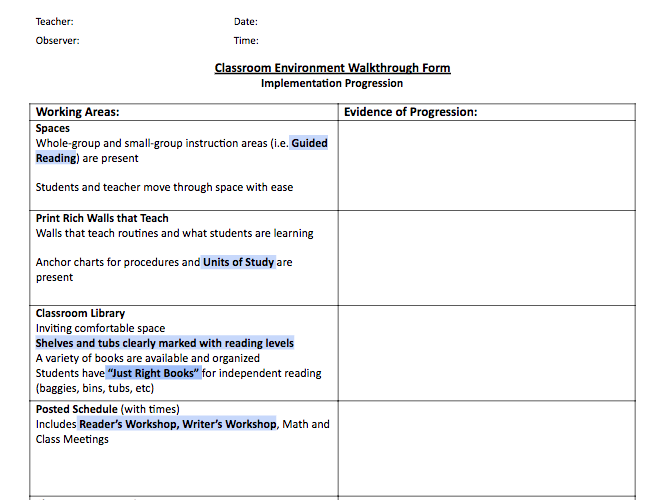

When I first became a literacy coach, I was tasked with helping teachers set up Balanced Literacy classrooms. Periodically, administrators toured our school with a checklist:

Of the items on their list, classroom schedules were the most important. The district’s Balanced Literacy Coordinator explained: “What I really care about is kids getting to spend time with books.”

Classroom agendas needed to include the language of Balanced Literacy — ”Workshop,” “Word Study,” “Interactive Read Aloud” — and resemble the district-provided example:

Every classroom allocated 15 minutes for Word Study, 30 minutes for Literacy Centers, and roughly 45 minutes each for Reading and Writing Workshop. We restricted our teaching to mini-lessons, believing that students would learn to read by reading.

First graders spent the same number of minutes on foundational skills as fourth graders, and that didn’t strike us as problematic. We gave phonics a light touch because we mistakenly believed that sounding out words was just one of many viable strategies for word recognition.

Our schedules perpetuated “The Matthew Effect” — students who could already read benefited (somewhat) from independent reading time, while those who were academically behind languished with low-level books.

Structured literacy schedules

When we learned the importance of explicit and systematic foundational skills instruction, our curriculum and classroom schedules changed.

Teaching a curriculum (stage 1)

Our curriculum called for differentiated groups so phonics could be taught to mastery, and this required time. We consolidated the time for “Word Study” and “Literacy Centers” to create a block during which reading groups rotated through activities and received a foundational skills lesson.

For a while, the name of the curriculum name appeared on classroom schedules, reflecting our commitment to teaching the lessons as written.

When we saw how effective our instruction was becoming, we wanted to take more ownership of that time. How we wrote our schedules varied, but we all agreed not to use the terms “Word Study,” “Guided Reading,” or “Workshop” because we wanted to show that our understanding of strong instruction had changed.

Teaching a curriculum together (stage 2)

We quickly noticed the opportunity cost of small-group instruction. It’s hard to ensure that students make good use of the time they spend without their teacher. However, small-group instruction can be 4-10 times more impactful than whole-class teaching (example research studies here , here , and a synthesis here ).

At my current school, we use a Walk to Read model, which reduces students’ independent work time and has a slew of other benefits.

In the first few years, instruction during Walk to Read looked nearly identical across classrooms. During a designated block of time, every teacher delivered two scripted, foundational skills lessons. But now, as achievement climbs, we’re ratcheting down the minutes for code-focused instruction because our students’ need for it has diminished.

Data-driven schedules

The chart below (based on the research of Carol Connor ), shows how instruction during Walk to Read can be adjusted according to student-need.

As students become proficient, we reduce the amount of code-focused direct instruction and increase the amount of time spent on meaning-focused and student-managed activities.

In addition to differentiated Walk to Read time, all students receive grade-level, meaning-focused instruction with their regular classroom teacher.

First grade example

First graders reading at grade level receive a daily 20-minute lesson including phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding, and spelling. Early in the school year, their teachers also facilitate choral reading from decodable text for an additional 15 minutes. As the school year progresses, these students master foundational skills and become confident readers who can enjoy short chapter books on their own.

Students working below grade level receive a hefty dose of direct instruction: 40-70 minutes/ day (with at least half the time spent reading decodable texts). Students participate in a 30-40 minute lesson and then are released to do partner reading or literacy games. Some students are then pulled for more targeted intervention in very small groups.

First graders above grade level currently require no phonics instruction. They can read grade level text, but do so slowly and without sufficient comprehension at the start of the year. Their instruction includes reading fluency, comprehension monitoring, and book discussions.

Almost full-circle

Balanced Literacy presented a vision — students reading, writing, and talking about books — but it didn’t offer a reliable path to get all kids there. By teaching foundational skills to mastery and adjusting the amount of direct instruction according to students’ needs, my school is increasing the number of students who enjoy cuddling up with a good book. We’re achieving the goal of Balanced Literacy by leaving behind its constructivist view of teaching.

A goal beyond fidelity

Prioritizing consistency across classrooms makes sense when schools adopt a new curriculum. It’s the most efficient way for teachers to learn a new program and to ensure that students receive instruction that builds from one year to the next.

But as new legislation and district policies aim to align teaching with the science of reading, critics claim that schools are being pushed towards adopting a packaged curriculum and implementing it without discretion. They say this movement is doomed to fail.

I worry that the critics might be right.

There has to be a next step in the works — an iterative plan that will allow teachers (ideally collaboratively) to adjust the amount and content of instruction according to their students’ needs. Implementing a curriculum as if all students need the same thing, at the same time, in the same dosage, ignores some of the most important findings from the science of reading.