When I became a reading interventionist, my first graders taught me that Guided Reading isn’t as effective as I had once believed. Initially, my attention was on my readers’ “strengths.” Mistakes in reading were not problems but rather “miscues,” windows into my students’ minds and reassurance that they needed me for guidance as they read.

But as I observed my students, I noticed them develop misunderstandings about reading.

Reading is memorization

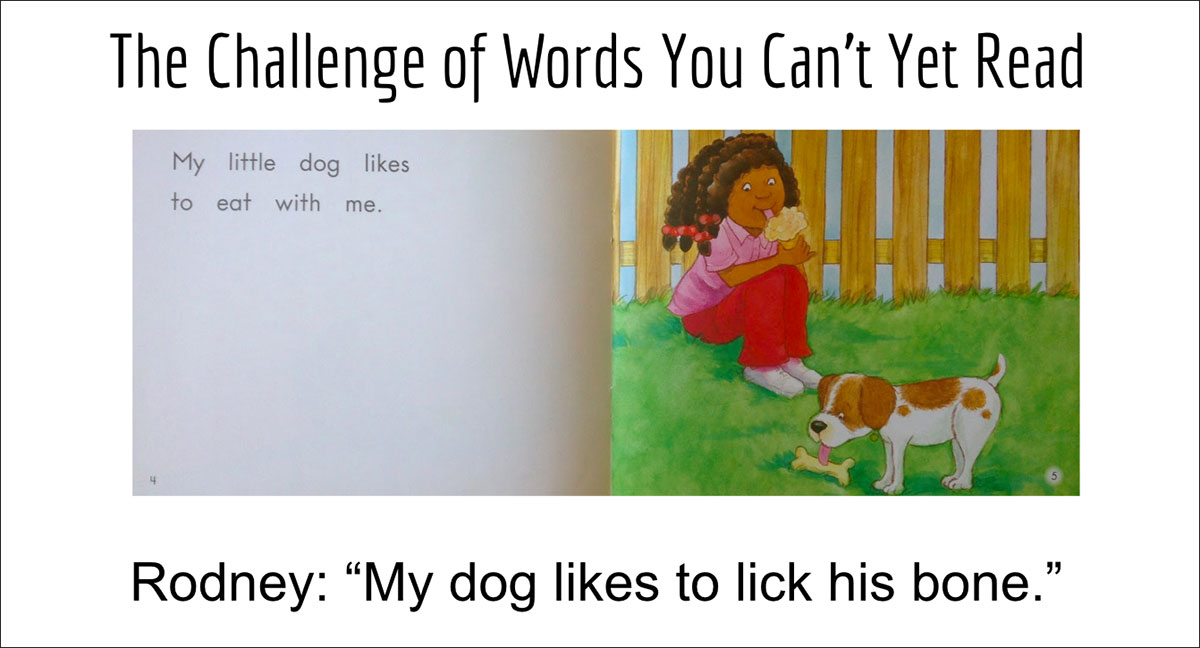

My students settled in to reread yesterday’s book, My Little Dog.

Rodney: “My dog likes to lick his bone.”

Rodney began to turn the page, unfazed by his miscues, so I prompted him to try again.

Another student interrupted: “It’s ‘my little dog likes!’”

I didn’t get any further in prompting Rodney before he reread the page correctly. He continued with the right pattern for the rest of the book, but the moment gave me pause.

Rodney wasn’t reading and he didn’t even know it.

Reading is making up stories

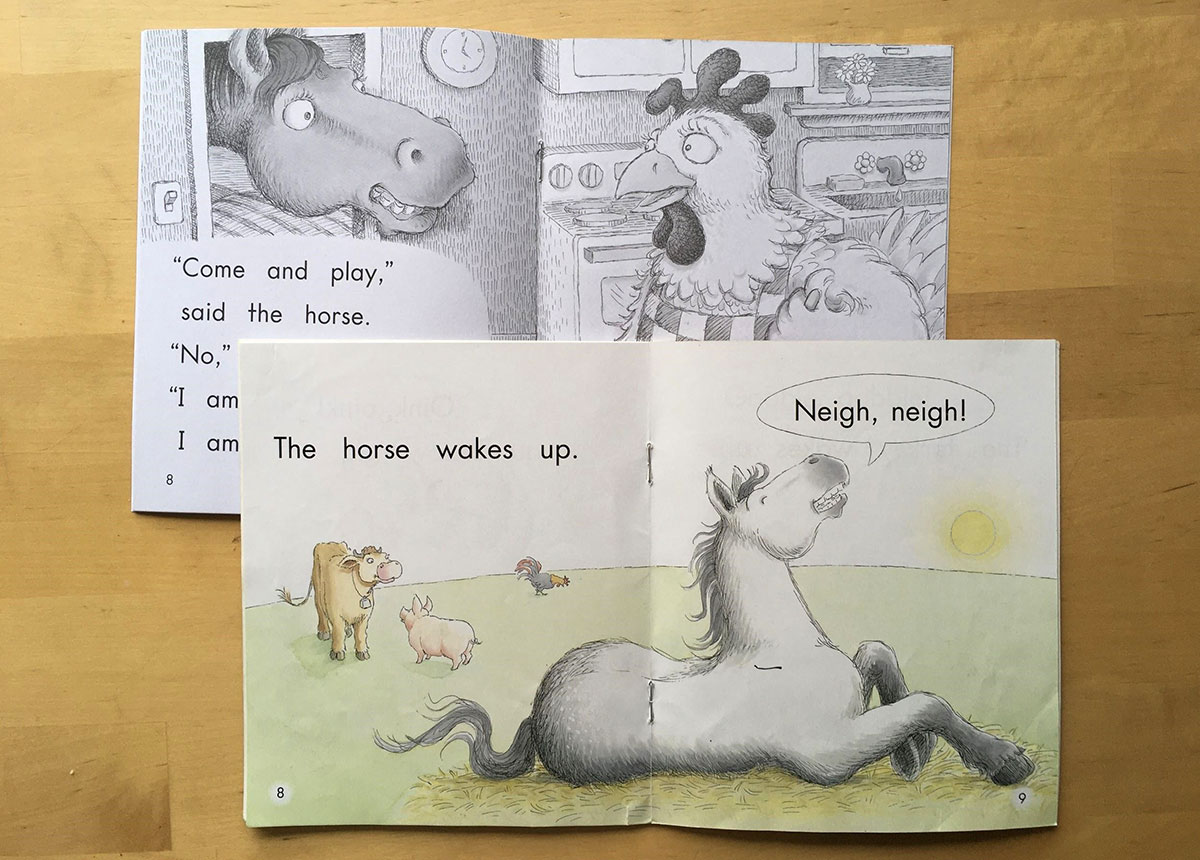

I was invited to watch the lesson of another teacher. The students reread yesterday’s book, The Very Busy Hen, but one child flipped through the pages and quietly recited words from a different predictable text about a farm.

What Armani did was no different than my students. Because they couldn’t yet read, they were making up or recalling stories.

The books were so predictable, I had no way of knowing if my students were reading. Even when they appeared to be reading accurately, they might have been reciting words from memory.

“I can’t read that book. I don’t know it.”

One student hadn’t begun her independent reading so I selected a leveled book from the book bin on her desk.

Me: “Will you read to me?”

Kalina: “I can’t read that book. I don’t know it.”

My stomach dropped. This was no different than Rodney, but it struck me harder this time. There is something wrong if students must know what a book says before they can read it. Reading is powerful precisely because books contain ideas we haven’t yet thought of.

“I can read this book with my eyes shut!”

Two months into first grade and after more than 30 Leveled Literacy Intervention books, my students still didn’t know that words are a necessary part of reading.

Angel: “I can read this book with my eyes shut!”

I had taught the phonics components of these lessons, prompted students to point to the words as they read, and called their attention to letter sounds they knew. But memorizing the patterns and using the pictures was easier for them than decoding and my students knew it.

I commited to reciting the refrain, “If you’re not looking at the words, it’s not reading.”

Reading requires only first and last letters

I showed my students a copy of Meli on the Stairs and pointed to the title,

Me: “Meli on…”

My students: “the steps!”

Me: “The word is stairs. Can you say, stairs? It’s another word for steps.”

And as I said this, I realized my students might have been able to read the word steps — most of them knew the letter sounds in that word — but they could not read stairs because I had not taught them long a. Why was I giving them a book with words they could not be expected to read? How could I teach them letter sounds and tell them, “It’s not reading if you’re not looking at the words,” but then give them words that didn’t match the phonics I had taught?

Reading is matching illustrations and words

I flipped through our next book, Homes and looked for words my students could read.

| Words My Students Could Sound Out | Words My Students Had Memorized | Words My Students Could Not Yet Decode |

|---|---|---|

log (2x) fox at (3x) crab bats web (2x) dog

| here (3x) is (12x) a (17x) for (8x) look (3x) this (8x)

| tree (2x) owl shell (2x) home (8x0cave (2x) hive (2x) bees spider hole (2x) mouse house |

As I looked more closely at the book, I saw there were opportunities for words my students could read (bug) but another word had been chosen instead (spider). Why? It was like the writer of the book wanted my students to pay more attention to the pictures than the words.

My students needed their instruction in first grade to prepare them for the texts they would soon encounter that had no pictures. I began to realize I was failing them.

“We don’t want students to pay too much attention to the letters.”

I approached the intervention coordinator about my concerns. I told her my students weren’t paying attention to the words in their books and that even if they did pay attention, they wouldn’t be able to read many of the words.

Coordinator: “That’s okay. We don’t want students to pay too much attention to the letters. That would slow them down as they read and they wouldn’t be able to make meaning of the text.”

Me: “But if they don’t slow down and pay attention to the letters and words now, how are they going to learn to read?”

Coordinator: “You know, there is more to reading than letters and sounds. The visual is just one part of reading. Meaning and structure are as important, if not more so.”

The lesson materials, training and data tracker I received directed me to teach my students that letters are not essential to reading.

| Date | Student Name | Story Title Reading Level | Accuracy % Self-Correction Ratio | Reading Behaviors: Strengths | Reading Behaviors: Challenges | Next Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9/29/2015 | John Adams | Bears Level B | 89% 1:7 | Uses letter-sound relationships to read words. Reads through the whole word. When able to read fluently, he understands what he reads.

| When he comes to an unknown word, he tries to read the word sound-by-sound and it takes him longer.

| Have student read up to the point of the difficult word, then cover the word and ask what word makes sense in the sentence. Then use the initial sound to read the word. |

But I felt I couldn’t teach my students that letters matter during writing time, only to cover them during reading. Leveled texts seemed to require guessing strategies that I couldn’t bring myself to teach.

Reading is frustrating

I no longer saw my students’ reading behaviors as strengths. I saw them using meaning and structure to compensate for their inability to decode. They relied on pictures, predictable language structures, and first or last letters to guess words.

Students who were English learners were unable to guess as effectively as those with larger vocabularies and so they would read bowl for dish and chicken for hen. This led them to confuse the letters and sounds I had taught them (b for d) and mispronounce words (chick-hen). It became harder to sell my students on new books because they knew as well as I did that they were not likely to be successful reading them.

Andrea: “Do we have to do a new book? Why can’t we just do the ones we know?”

Teaching reading is frustrating

My colleagues were also struggling. Some of them went in search of materials intended for kindergarten because they wanted more books their students could appear to read and the first grade kit had gotten too hard.

One interventionist asked our leaders: “Do you want me to teach LLI or do you want me to teach kids to read?”

I wasn’t the only one who felt that what our students were doing wasn’t reading.

Another interventionist: “This cueing thing isn’t reading. They are pretending to read and we are pretending to teach.”

I was done pretending. Done with guided reading. And ready to learn how to teach reading in a way that communicated to my students that meaning and enjoyment can be derived from the words on the page.

I threw myself into researching reading because my students were waiting for me to teach them. It wasn’t easy, for me or for them, but the only regret I carry is that I didn’t do it sooner. I had been teaching for almost ten years before I began learning about the instruction most children need to become skilled readers.