About this interview

Carle opened the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts in 2002. The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer filmed the grand opening and graciously shared their interview with Reading Rockets.

Biography

Eric Carle was born in Syracuse, New York in 1929. In kindergarten, he enjoyed a classroom filled with colorful paints, big brushes, and large sheets of paper. But when Carle was six, his parents moved back to their native Germany. Young Eric had a hard time adjusting to a new culture and a first grade class with little room for creativity. Carle often asked his mom when they were going back home to New York. He dreamed that, when he grew older, he would build a bridge from Germany to America.

As a young boy, Carle loved taking walks with his father and learning about nature. But when he was 10, World War II started and his father was drafted into the army. For the next six years, their family endured many hardships. Carle’s neighborhood was bombed by the Allies and his father did not return home for years. Yet amidst the chaos of the war, Carle pursued his love for art with the support of a high school art teacher.

In 1952, after graduating from a prestigious art school in Stuttgart, Carle returned to New York. He had an impressive portfolio but just $40 in his pocket. Carle found a job as a graphic designer for The New York Times and later worked as the art director for an advertising agency. When one of Carle’s bright collages caught the eye of children’s book author Bill Martin Jr, Martin hired Carle to illustrate Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? In 1969, Carle published The Very Hungry Caterpillar, a small book that endeared him to a generation of children and adults around the world. It has now been translated into 33 languages and sold over 18 million copies worldwide.

In 2002, Eric Carle founded and opened the first museum in the country dedicated exclusively to children’s picture book art. Located in Amherst, Massachusetts, The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art welcomes “children, parents, teachers, librarians, and other lovers of children’s picture book art.” In 2003, Carle became the thirteenth recipient of the prestigious Laura Ingalls Wilder Lifetime Achievement Award for his “substantial and lasting contribution to literature for children.”

To learn more about Eric Carle’s life, books, and contribution to children’s literature, visit the official Eric Carle website. Eric Carle died in 2021 at the age of 91. In remembrance:

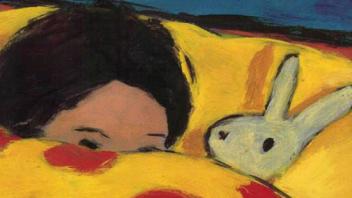

In the light of the moon,

holding on to a good star,

a painter of rainbows

is now traveling across the night sky.

“Bright collage images, imaginative stories, and little details — die cut pages, a firefly’s twinkling lights, a quiet cricket’s song — made Eric’s illustrations uniquely playful. He remains an important influence on artists and illustrators at work today.”

Books by this illustrator

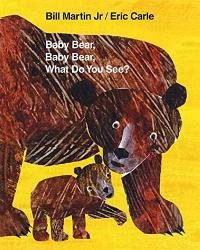

Baby Bear, Baby Bear, What Do You See?

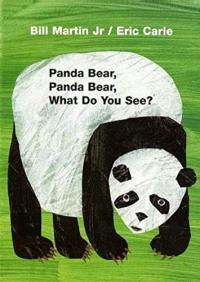

Panda Bear, Panda Bear, What Do You See?

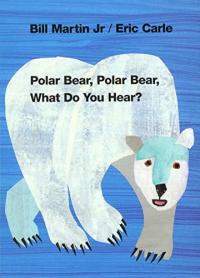

Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What Do You Hear?

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Animals All Around

Themed Booklist

Comforting Classics

Themed Booklist

Field Trips and Other Adventures

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2004

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2008

Themed Booklist

Imagine!

Themed Booklist

Life’s Ups and Downs: Emotions and Accomplishments

Themed Booklist

March Magic

Themed Booklist

Old Friends for the New Year

Themed Booklist

Sleepytime Books

Themed Booklist