What do current researchers think about how reading develops? While our brains are wired for spoken language and we learn to speak through exposure, we must be taught how to read. Reading instruction changes our brains’ structure and how they work. Once we learn to read, we can’t turn it off! Our brains automatically process print that we see with no conscious effort on our part.

The human brain is capable of handling a vast and complex array of operations needed to read print. But these reading components are not easily separated or taught in isolation. As Marilyn Adams (1994) describes, “the parts of the reading system must grow together. They must grow to and from one another” (1994, p.785).

The “reading brain”

Scientists learned that there are four brain regions that are related to reading:

- the visual cortex that helps us perceive letters and words

- the phonological cortex that maps the sounds to letters

- the semantic cortex that stores word meanings, and

- the syntactic cortex, that helps us understand the rules and structure of sentences

Each part of the brain works in concert by forming efficient and fast neural pathways as we read.

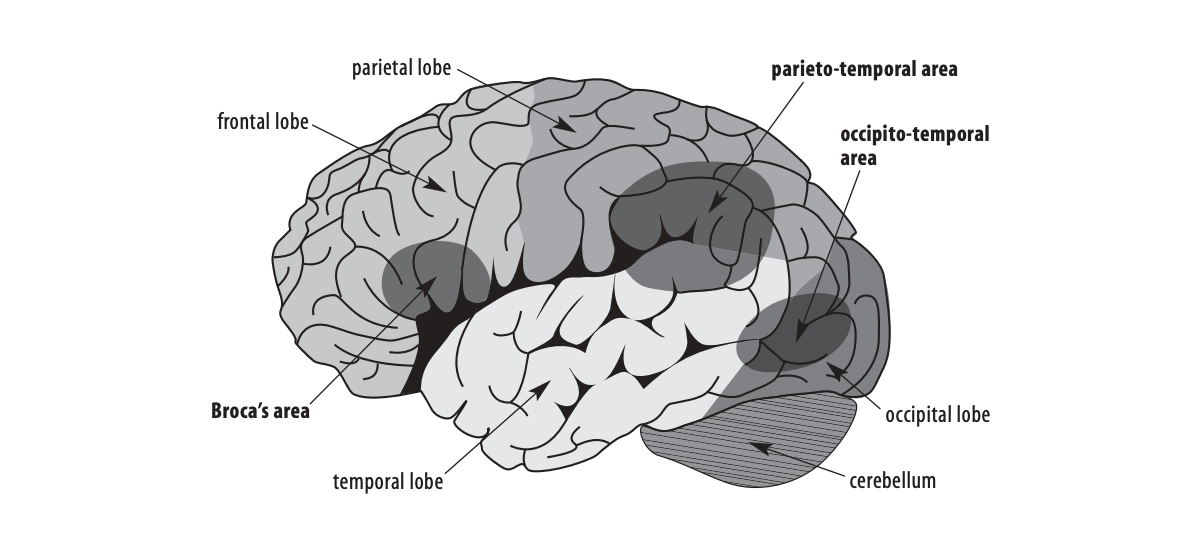

The brain consists of two sides or hemispheres. Each side can be divided into four lobes or regions: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. The left side of the brain is associated with language processing, speech, and reading. Each lobe has a unique role in reading words and they interact to link printed words with letter sounds and meaning:

- Parietal-temporal region, where a written word is segmented into its sounds (word analysis, sounding out words).

- Occipital-temporal region, where the brain stores the appearance and meaning of words (letter-word recognition, automaticity, and language comprehension).

- Frontal region, where speech is produced (processing speech sounds as we listen and speak).

Excerpted from Teaching Reading Sourcebook, Third Edition. Honig B., Diamond L. & Gutlohn, L. (© 2018 by CORE)

How reading takes place in the brain

When we read, our brains transform the shapes of letters and characters on a page into the sounds of spoken language. But how does the brain do this? That’s what cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene (Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read) is trying to find out. Dehaene, a professor at the Collège de France and a winner of the 2014 Brain Prize, studies how reading takes place in the brain and his research has revealed the brain networks involved. Learn more about his research — and its implications for how we teach reading — in this video.

What has scientific research taught us about how children learn to read? And how well has that penetrated the classroom?

Cognitive scientist Dr. Mark Seidenberg says that the “hallmark of skilled reading is the integration of print with what a person knows about the spoken language.” Seidenberg also talks about what we have learned from brain imaging.

Understanding reading disabilities

Neuroscientists study the brain and how its functions. Advances in neuroscience confirm what we know about learning to read, spell and write. In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s fMRI studies of students’ brains while performing reading tasks demonstrated structural and functional differences in skilled and poor readers’ brains (Eden, G.,1996, 2002; Meyer et al, 2008; Shaywitz et al., 2002, 2004). The brain scans of students with dyslexia are different in at least two ways:

- Their brains are less active in the left hemisphere where language is processed, and

- Their brains are overactive in other areas of the brain to compensate

What’s really exciting is that studies from neuroscience suggest that reading intervention may actually change the way struggling readers’ brains work (Barquero, Davis, & Cutting, 2014). Students who respond to word-focused interventions may be able to change how their brain functions to make their reading easier and more efficient. This is a promising area for research.

What’s different in the brain of a person with dyslexia?

Dr. Guinevere Eden is a professor in the department of pediatrics and director of the Center for the Study of Learning (CSL) at Georgetown University. She uses MRI scans to map brain activity and study the biological signs of dyslexia. Eden hopes that this will soon make it possible to diagnose dyslexia very early in children.

Teachers, you are changing brains

Dr. Guinevere Eden says that as you learn to read, your brain is changing. For children who struggle to become skilled readers, teachers can provide crucial help — through intensive interventions that activate regions of the brain that support reading.

Learn more from the experts

Watch our video interviews with researchers who study the “reading brain” and the use of neuroimaging in early identification of children with dyslexia and other reading disabilities.

- Nadine Gaab (Harvard University)

- Guinevere Eden (Georgetown University)

- John Gabrieli (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Mark Seidenberg (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Related resources

By Amplify

Science of Reading: A Primer (Part 1)

Launching Young Readers

Reading and the Brain

Themed Booklist