Biography

Marc Aronson is an author, editor, publisher, speaker, and historian who believes that young people, especially pre-teens and teenagers, are smart, passionate, and capable of engaging with interesting ideas in interesting ways. He has written history and biography nonfiction books for children and young adults, as well as nonfiction books for adults about teenage readers. He has become a strong voice for the role of high-quality nonfiction in support of the Common Core State Standards.

Aronson has written about larger-than-life contemporary figures such as J. Edgar Hoover and Robert F. Kennedy, as well as compelling historical figures like Oliver Cromwell and Sir Walter Raleigh. He has also researched and written sweeping in-depth books about the history and impact of the sugar trade, the cultural history of the avant-garde from 19th century Paris to today, the Salem witch trials, and a global history of race and relations.

In all of his work, Aronson’s mission is to inspire young people to ask questions, and to look deeply inside the stories the world brings us. He encourages kids to see themselves as detectives, examining the clues history has left behind, or as reporters, telling the truth about the modern world. Aronson says, “All of my books start with questions, and I hope they prompt readers to ask questions of their own.” Aronson also visits schools where he talks with teens about history and the arts, and leads workshops for teachers, librarians, and parents on topics such as how to get boys to read (he’s a supporter of the Guys Read project).

Aronson has a Ph.D. in American history from NYU. He lives with his wife, the author Marina Budhos, and two sons in Maplewood, New Jersey.

Books by this author

The search for the man who beat a steam engine unfolds in words and pictures. The mystery in history is sure to intrigue readers.

Ain’t Nothing but a Man: My Quest to Find the Real John Henry

A fictionalized journal of a prospector brings the Gold Rush to life for readers. Fact and fiction are clearly differentiated while enlivening the history.

How to Get Rich in the California Gold Rush: An Adventurer’s Guide to the Fabulous Riches Discovered in 1848

Another fictionalized account which brings to life westward expansion. As with …California Gold Rush, fact is made distinct from fiction.

How to Get Rich on the Oregon Trail

No matter how much is known, there’s always more to learn. In a fascinating re-examination of Stonehenge and recent discoveries, readers are introduced to new interpretations and thinking.

If Stones Could Speak: Unlocking the Secrets of Stonehenge

As a young student, Mayor wondered: Is the mythical griffin based on ancient people’s interpretations of dinosaur bones? This biography shares her fascinating efforts to prove her theory correct and reveals other connections between science and human myth as well. (School Library Journal)

The Griffin and the Dinosaur: How Adrienne Mayor Discovered a Fascinating Link Between Myth and Science

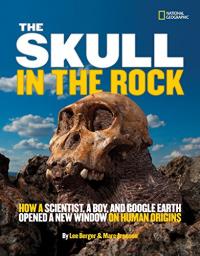

In 2008, Lee Berger and his 9-year old son discovered two well preserved fossils, ancestors of modern man. The process as much as the ripples the discovery created remind readers that information is dynamic.

The Skull in the Rock: How a Scientist, a Boy, and Google Earth Opened a New Window on Human Origins

The world was changed forever in 1492. The impact of explorers and exploration is examined and placed in a broader context with complete documentation and resources noted.

The World Made New: Why the Age of Exploration Happened and How It Changed the World

How 33 Chilean miners were rescued from a copper mine dominated the media in 2010. It is recounted here using primary sources, scientific explanations, and a riveting narrative.