Why choose Patricia Polacco?

Polacco has written lots of great stories drawn from her own family. Her stories are realistic, filled with humor and drama, and are accessible — even to reluctant readers — because they are in a picture book form.

What age is most appropriate for a study of Polacco?

Patricia Polacco’s picture books are most appropriate for older elementary studies (grades 3–5), although older children and adults can appreciate her work, too. This is particularly true for several of her books, such as Pink and Say and The Butterfly, which include difficult scenes related to war.

(Note: A handful of Polacco’s books, such as G Is For Goat are clearly meant for preschoolers.)

Polacco’s work uses the picture book format. Some older elementary kids view picture book as “baby” books, and teachers might have to sell these books a bit. So it’s important to start with a high-interest book.

This author study begins with Polacco’s tale of sibling rivalry with her brother, My Rotten Red-Headed Older Brother as a way to pique students’ interest and show that these books are for older readers like them.

Patricia Polacco: The 15-Day Study, in Depth

We’ve developed a sample author study using the popular author and illustrator, Patricia Polacco, as the model. Here, we offer details on each of the six units in the author study. The introductory unit is a two-day study of Polacco’s book My Rotten Red-Headed Older Brother. The next four two-day units focus on different books by Polacco: My Ol Man, The Butterfly, Pink and Say, and Thank You, Mr Falker. The final unit stretches for five days, giving students time to work through their classroom activities and complete their final projects.

Introductory Unit (Days 1 and 2): My Rotten Red-Headed Older Brother

Day 1: Introduce the author study and Patricia Polacco

Begin by telling students that, for the next three weeks, the class is going to do an activity called an “author study.” Explain that the class will read together five books by one author, and that students will be encouraged to read more books by the author in their silent reading time and in at-home reading. Tell students that the class also will learn about the author herself, and do various classroom activities related to each of the five books. Conclude by telling students that they will be required to do a final project, with work being done both in class and at home, to show what they’ve learned during the author study.

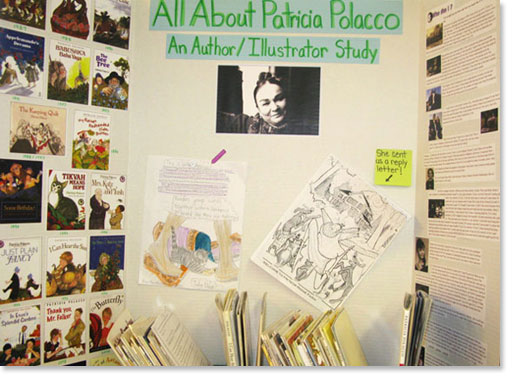

By now, students will (hopefully!) be wondering which author they will study. Hold up a couple of Patricia Polacco’s books — perhaps the first two to be studied — and announce that Patricia Polacco will be the focus of the author study. Show students a photo of Polacco and then pin that to the center of a display board labeled something like “All About Patricia Polacco” or “What We’ve Learned about Patricia Polacco.”

Show students all five of the focus books, one at a time, and ask if students have read any of the books. (You could also show some of Polacco’s other books, such as Thundercake or Chicken Sunday, which are among her best-known). If students have read some of Polacco’s books, and wonder why they have to read them again, express great enthusiasm for Polacco’s books. Explain that one reason you chose Polacco is because you really enjoy her books and want to share them together with your students.

At this point, it’s also important to introduce another main reason for studying Polacco’s books — the idea of the importance and interest of family stories. Talk to students about how almost all of Polacco’s many books are based on stories from her family, stories that she shares with readers in both words and pictures. Emphasize that everyone has family stories and that one of the class activities during the author study will have students writing and illustrating a story from their own families.

Because some students may be reluctant to read picture books (“Those are for babies,” some older elementary students contend), explain that just because a book is published in a picture book format, that doesn’t mean it is for young children. For example, two of Polacco’s books, The Butterfly and Pink and Say, are most appropriate for students ages 8 and up because they include scenes of death and violence.

You can share that many of the books that have won the Caldecott Medal — awarded each year to the best illustrated children’s book — are picture books most appropriate for older children (examples: Smoky Night, Golem, So You Want to Be President?, Snowflake Bentley, and The Man Who Walked Between the Towers). Explain that the librarians who award the Caldecott Medal look at picture books appropriate for ages birth through 14 and that’s why the winners aren’t always for very young children.

Teachers, here’s one more rationale for doing an author study on a picture book author/illustrator, which is at least important for you to know. We live in a visual world, and students constantly are seeing pictures and words on the many screens to which they are exposed each day, from computers to video games to television. Yet little emphasis still is placed in schools on the idea of teaching visual literacy — helping students learn how to “read” pictures. Doing an author study on a picture book author/illustrator like Patricia Polacco is one way to help improve students’ visual literacy.)

After taking questions from students about the author study, tell them you’re going to begin reading aloud the first of the five focus books for the study. We’re starting with My Rotten Red-Headed Brother as a way to spark immediate interest in students for Polacco’s book. Most students have siblings and even those without siblings understand the powerful and sometimes contentious bond between brothers and sisters. Polacco’s real-life account of dealing with her older brother is a great way to invite students to begin appreciating Polacco’s work.

Day 2: Take a book walk, explore the characters, and share a personal story

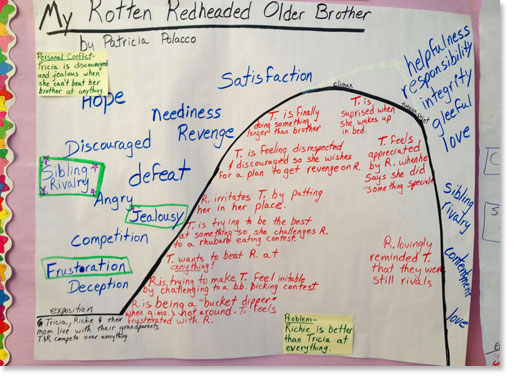

It’s time to look more closely at our first Polacco book, My Rotten Red-Headed Brother. Begin by paging through (not reading) the book again, highlighting the illustrations this time, asking students how the artwork adds further detail and emotion to Polacco’s text. Then ask students what they most enjoyed about the book and whether it seemed like a realistic look at sibling rivalry.

Ask students who their favorite character is, and what that character is their favorite. Finally, have them look closely at the author’s dedication; this book about her often troublesome older brother is dedicated to that same brother, showing that their differences have not kept them from developing a close bond.

Then lead the class in comparing and contrasting Patricia and Richard, making a Venn diagram showing how they are similar and how they are different. Simple differences, for example, are that Patricia is a girl and Richard is a boy. Students may have a more difficult time coming up with similarities, which might include the fact that both are stubborn, both are adventurous, etc.

After completing this task, it’s time for “wonderings and guessings.” Ask students what clues they found about Polacco herself in the book. Look particularly at the photos included in the endpapers. Add those to the “All About Patricia Polacco” chart. Help students locate Union City, Michigan on a map of the United States.

Finish by explaining the homework assignment for this book in which students will write a brief story about a time they clashed with a sibling and how they solved the problem. If students don’t have a sibling, ask them to ask their parents to share a story of sibling rivalry from their childhood. Students should do their writing in their author study notebook. If they want, students also can do an illustration of their favorite character.

Days 3 and 4: My Ol’ Man

Day 3: Explore family and build a relationship map

Read My Ol’ Man to the class. Ask students to talk about the characters. What kind of a person was Da — Polacco’s father? Do they know anyone else like him?

This book is realistic non-fiction, but it also includes an element of magic as Polacco talks about the family’s lucky rock. Ask the students if the rock really bring the family luck? Or is it really their belief in the magic of the rock — not the magic itself — that helps them keep their spirits up when things look grim?

Finish the day by creating a “relationship map” with the class. This map will be centered on Polacco’s father. Ask students how Patricia, her brother and grandmother fit into the map, as well as the only non-family character, Bill Barber.

Day 4: Look closely at the illustrations and create a story web

Page through the book again, just showing the illustrations. Talk about the details, such as the food scattered on the dashboard and on the seat of Da’s car in one of the early illustrations and photos that Polacco uses in her illustration later in the book when Gramma gives Patricia the supplies she needs to do art. Ask students how Polacco portrays emotion through her illustrations (i.e. the way characters are drawn, the colors chosen, and Polacco’s use of perspective).

Time for “wonderings and guessings.” Ask students what further clues they’ve learned about Polacco from this second book, and add them to the “All About Patricia Polacco” chart.

Ask students to help you make a web that graphically illustrates the major aspects of My Ol’ Man: main characters, plot, setting, and problems/solutions. Ask students for help in filling in the web. (Note: students often find it hard to pare down the plot to a bare minimum. Sometimes it can be helpful to start by asking what is the main problem in the book, and how is it solved. Then, help students break down the plot into its most basic elements).

For homework, ask students to write a brief biography of a parent or grandparent, giving just highlights of their life. If students want, they can also illustrate the biography, which should be written in their notebooks.

Days 5 and 6: The Butterfly

Day 5: Provide background knowledge on WWII, and a first read

Begin by telling students that the next two Polacco books they will read — The Butterfly and Pink and Say — take place during wars. The Butterfly takes place during World War II, while Pink and Say is set during the American Civil War.

Explain that before reading the next book, The Butterfly, you’re going to give students a brief overview of World War II.

Then use a map of the world to show where World War II was fought, and talk about the main groups of combatants, telling how there were two main “theaters” of war — Europe and the Pacific. Briefly explain how World War II started in Europe with Hitler’s rise to power, then note that the United States didn’t enter the war until two years later, when the Japanese attacked our country at Pearl Harbor.

Talk about how, after years of nearly losing to Hitler, the Allies turned the tide and stopped Hitler. Finish by telling students that the war finally ended in 1945, after the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan and forced the Japanese to surrender. (A good source of basic information about World War II is the DK Eyewitness book simply titled World War II by Simon Adams, which gives a good overview and has lots of photographs and maps).

Tell students that you know are going to read The Butterfly, which is set in France during World War II. Give them a bit more background: the Nazis, under Hitler, took over France in 1940; many French people resisted Nazi rule, but had to do it secretly or they would be killed; one of Hitler’s goals was to get rid of all Jewish people and, in fact, the Nazis had killed six million Jews — men, women and children — by the end of World War II.

Finally, with this background, it’s time to read The Butterfly. Prepare children a bit by telling them that this is a sad story but one that shows how courageous people can be, even risking their lives, as they try to help other people.

Day 6: Analyze the illustrations and main themes

Page through the illustrations with the students, noting how Polacco uses color to express fear and intensity. In addition, ask students to look at Polacco’s use of black and white in this book.

The Butterfly often elicits many questions from children who want to talk more about why Hitler was trying to kill Jewish people. Let them ask questions (answering as best as you can, with World War II resources at hand). Then lead a discussion about why Monique’s mother risked her life and her family’s safety for another family. Was that fair to her family? Or are other things sometimes more important than being safe? Ask students to try to imagine themselves in a similar situation. What would they do?

Do the “wonderings and guessings” exercise, asking students what clues they picked up about Polacco and her family in The Butterfly.

If there’s time, lead the class in a “chunking” activity, asking them to list the main ideas and events in The Butterfly.

For their homework, ask students to write down their thoughts and feelings about reading The Butterfly. Did they enjoy the book? Why or why not? Did they feel scared by the story Polacco tells? What did they learn from the story?

Days 7 and 8: Pink and Say

Day 7: Provide background knowledge on the U.S. Civil War, and a first read

Begin by telling children that you are going to read another Polacco book based on a war. But this book, Pink and Say, is based on a war that happened nearly 100 years before World War II. The war that is the focus of Pink and Say is the U.S. Civil War, which took place from 1860-1865.

Once again, provide a bit of historical background so students will be better able to appreciate and understand Polacco’s story. Give some basics about the U.S. Civil War, using a U.S. map; i.e. the war was fought between northern states (Union Army, led by President Lincoln) and southern states (Confederate Army, led by General Robert E. Lee) over whether slavery should be legal.

Explain how slaves were regarded as the property of their owners, how they were often mistreated and even murdered by their owners, and how slave families were split apart as owners sold the children of slaves to other owners.

Conclude by noting that, even though the North won the Civil War and slavery became illegal, African-Americans didn’t get their full rights under law until 100 years after the Civil War ended when Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. (Note: A good book for background on the U.S. Civil War is the DK Eyewitness book Civil War by John Stanchack).

Read Pink and Say.

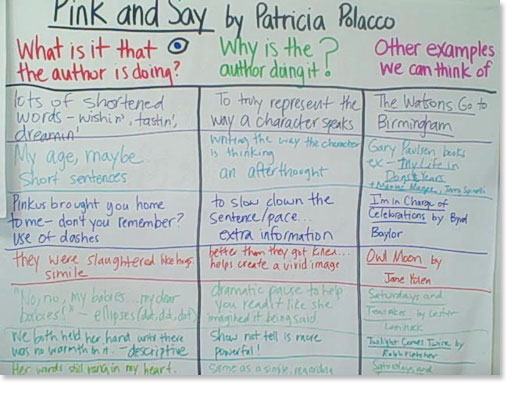

Day 8: Analyze the illustrations and main themes, write a book review

Once again, page through Polacco’s book, just looking at the illustrations. How does Polacco use color and line to depict emotions? Note that, once again, Polacco uses real photos in the last illustration in the book. Why does she do this?

Like The Butterfly, Pink and Say often elicits many questions from children about slavery and the Civil War. Answer as many questions as you have time for. Ask students what they think about the idea of one person owning another person. And ask them to think about the bravery of Pink and his mother in taking in Say and helping him to get well. Why would Pink decide to save the life of Say, a white man, when Pink and his mother have been mistreated all their lives by white people?

Do the “wonderings and guessings” exercise, asking students what clues they found about Polacco and her family in this book. Add them to the “All About Patricia Polacco” chart.

Ask children if reading books like The Butterfly and Pink and Say changed their idea about picture books being for little children. Why or why not?

Lead the class in an activity comparing and contrasting Pink and Say, using a Venn diagram.

For homework, ask children to write a brief review of Pink and Say in their author study notebook. Did they enjoy the book? Why or why not? What was the best thing about it? What didn’t they like? Who was their favorite character? Why? Who else would like this book? What age reader would they recommend the book for? If students want, they can also illustrate a favorite scene from the book as artwork for their review.

Days 9 and 10: Thank You, Mr. Falker

Day 9: Explore how the illustrations and text work together

Tell students that the class will be reading their final focus book by Polacco in the author study.

Instead of reading the text, however, tell the students that the class will be reading the book first solely by looking at the illustrations. Page slowly through the book showing students the illustrations. Then ask them to predict what they think the book may be about.

Why would someone pour honey on a book (first illustration)? Why is the girl, who seems to be the main character, so upset in an illustration in the middle of the book that shows her crying and a trio of boys laughing by a fence? Why does the next-to-last illustration show the girl reading a book with what looks like a shooting star near her head?

After discussing the predictions, read the book again, this time just reading the text and NOT showing students the illustrations. Ask children to think what illustrations they remember fit what parts of the text you just read.

Finally, read the book, showing the illustrations. Ask students if the story would be as good without the illustrations, or do the illustrations add something the text doesn’t have. (Note: this is basically a lesson on how picture books balance text and illustrations. In the best picture books, words and pictures work together seamlessly — the book isn’t whole without both of them.).

Day 10: Share a personal story and write about your favorite Polacco book

Do the “wonderings and guessings.” What did students learn about Polacco from Thank You, Mr. Falker? Were they surprised to learn that the author had such a hard time learning to read? Add the information to the “All About Patricia Polacco” chart.

Ask students if they have ever had trouble learning something in school. How did they feel about it? What did they do about it? Have they ever had a teacher like Mr. Falker, someone who was helpful to them in understanding a difficult school subject?

What about the students who made fun of Trisha? Do students know kids like this? Has this ever happened to them? What did they do about it?

Ask students if they remember when they first learned to read. How did it feel?

It’s time to begin to tie together the five focus books. Create an “attribute chart” in which students record what they see about various aspects of Polacco’s work in the five books: illustrations, characters, language and story problems/solutions. Students can use examples from particular books, but the idea is to try to put together an overall picture of Polacco’s work from the five books.

For homework, ask students to write in their notebook about which was their favorite of the five focus books. Why was it their favorite?

Days 11 to 15: Final classroom activities

Day 11: Develop a biography of Polacco and a family tree

It’s time to have the class put together a biography of Patricia Polacco. By this point, students should have been to the media center to do research on Polacco. Now, take the “All About Patricia Polacco” chart and go through it, point by point, asking students if the clues written on that chart are correct, according to the information they learned about Polacco in the media center. As students sift through the information, write down the “Polacco Facts” on a poster board.

Once this activity is complete, lead the class in putting together a brief biography of Polacco. Ask students to look at the “Polacco Facts” poster board as they work together with you in writing a biography of the author. As students dictate facts to you, help them put the facts in sentences, writing them on a poster board.

Ask if the biography should be written in chronological order, or if perhaps it might be good to start by highlighting a particularly interesting fact about Polacco (i.e. not learning to read until she was in the fifth grade) and then going “backwards” into her life.

In the biography, underscore the fact that most of Polacco’s books (and all of the five focus books) are based on Polacco’s family stories. Don’t forget to include how Polacco reaches back through generations to come up with some of her stories, as in The Butterfly and Pink and Say.

Now the class can create a Polacco “family tree,” using what they learned from Polacco’s books and their own research. (Note: Prepare ahead of time by cutting a large tree with branches out of construction paper and pasting it onto a poster board).

Finally, ask students to talk about which was their favorite of the five books and why (using their homework from the previous night). Create a graph showing the results.

Day 12: Begin work on individual final projects

Students can use class time to work on their final projects. These are individual projects, and so students should be working generally on their own.

Day 13: Continue work on individual final projects

Students continue working on their final projects.

Day 14: Present final projects

Students begin presenting their final projects.

Day 15: Present final projects

Students finish presenting their final projects.

If time and budget permit, wrap up the author study with a little celebration, in which students toast Polacco with fruit juice. Tell students that each one will get a chance to offer a toast, mentioning a favorite character, scene, book, illustration or other aspect of Polacco’s books as they raise their glass.