Imagine three different children reading the following page from the popular story, M & M and the Bad News Babies, by Pat Ross.

Mandy put a pink sea castle into the fish tank.Mimi added six yellow stones that glowed in the dark.The friends M and M had been fixing up the old fish tank all week.”Now all we need are the fish,” said Mimi. “But fish cost money,” said Mandy.

Think about what the following readers did to understand this passage.

Reader 1: Mark is familiar with other stories about the two friends M and M and already knows that this story is an adventure about two girls named Mandy and Mimi. With this knowledge, he made a connection between what he already knows about the book series and this story. Mark knows that the author gives clues about the girls’ adventures in the title, so he predicted that the two girls would try to earn money to buy fish for their fish tank and that their attempts will result in mishap. Finally, he ended by asking himself, “What kind of trouble will Mandy and Mimi get into in this story?”and turned the page to read more.

Reader 2: Lizzy is not familiar with other stories about M and M. Instead of making a text-to-text connection, she quickly previewed the text and activated her prior knowledge about fish tanks. Lizzy made a text-to-self connection between her prior knowledge and the information in the story. She knows that people put different things in their fish tanks to decorate them and that fish cost money. Finally, she asked herself, “How will Mandy and Mimi earn money for the fish they want?” and turned the page to read more.

Reader 3: Paul also quickly previewed the text, realizing that he doesn’t know anything about fish or fish tanks. He imagined that the friends must have anew hobby, pet, or homework assignment. While he doesn’t know about fish, Paul does know about earning money by doing chores. He made a text-to-world connection between his prior knowledge and clues from the passage. He ended his reading by asking himself, “I wonder if Mandy and Mimi will do chores to earn money for the fish they want?” and turned the page to read more.

These examples demonstrate three paths to understanding the passage. Each path requires “in the head” strategies before, during, and after reading. The different paths help demonstrate that reading is an active thinking process and reveal what good readers do as they read. All children — whether struggling or proficient readers — benefit from learning to internalize and apply these comprehension strategies.

This article will provide you, the tutor, with proven techniques for helping students acquire comprehension skills and strategies. Using these strategies to support students’ developing abilities to read strategically and actively will make your work more effective. In addition to building your own background knowledge about comprehension, you’ll explore six comprehension strategies and follow a tutor, Tina, and her student, Allison, through activities and conversations that support each strategy.

What is comprehension?

Comprehension is the “essence of reading” (Durkin, 1993). It is a complex thinking process that requires the reader to construct meaning from the text.

The well-known children’s author, Katherine Paterson, describes the relationship between reader and writer this way:

Once a book is published, it no longer belongs to me… The work now belongs to the creative mind of my readers… It’s a wonderful feeling when readers hear what I thought I was trying to say, but there is no law that they must. Frankly, it is even more thrilling for a reader to find something in my writing that I hadn’t until that moment known was there.”

Katherine Paterson

Children need explicit instruction in reading comprehension. The role of the tutor is to help children become aware of the variety of problem solving strategies that enable them to independently understand, discuss, and interpret text. Children who are given this kind of support become moreproficient readers (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Let’s look at what good readers do.

Good readers have strong listening comprehension skills. Comprehension develops through reading and listening to texts read aloud (Honig, Diamond, & Gutlohn, 2000). For young children and beginning readers, listening to someone read aloud provides opportunities for them to comprehend text they would not be able to read for themselves (Gillet & Temple, 1994). Developing children’s listening comprehension helps them become more skillful at text comprehension (Fountas& Pinnell, 1996).

Good readers recognize that reading is more than decoding words. Decoding is the ability to sound out a written word and figure out the spoken word it represents. While children cannot understand text they cannot decode, it is also true that decoded words are meaningless unless they are understood (Maria, 1990).

Good readers make connections. Good readers experience the wonderful sensation of getting lost in text. They relate what they read to other books, to their own experiences, and to universal themes and the world around them. These types of connections are called text-to-text, text-to-self, and text-to-worldconnections (Keene & Zimmerman, 1997).

Good readers think about their thinking. Good readers are aware of their own thought processes (Honig et al., 2000). Irvin (1998) points out that explicit instruction in comprehension skills helps develop children’s metacognition — the ability to think about their thinking. Good readers use metacognition to “think about and have control over their reading” (Armbruster, Lehr, & Osborn, 2001).

Good readers read a lot of good books! To be good readers, children need to read a lot. Allington (2001) points out that reading practice is a powerful contributor to the development of accurate, fluent ,high-comprehension reading. Your work as a tutor not only provides additional learning time, but additional reading time for the children you work with. Increasing the volume of children’s reading and helping them develop comprehension strategies are characteristics of effective reading support (Donahue, Voelkl, Campbell, & Mazzeo, 1999).

What are the comprehension strategies?

Research has shown that a major aspect of reading instruction is transforming comprehension skills into explicit strategies we teach to students (Simmons & Kameenui, 1998). Children need to learn to use comprehension strategies before, during, and after they read. Tutors need to explicitly model comprehension strategies and help students understand when and how to use them (Honig et al., 2000).

Comprehension strategies

Research strongly supports the following strategies (Allington, 2001; Armbruster et al., 2001; Farstrup & Samuels, 2002):

Activating prior knowledge

Previewing a story before reading using techniques such as “picture walks” helps children make connections between the story and what they already know.

Answering and generating questions

Asking children questions helps them focus their attention and think actively about the text. Inviting children to question the text also demonstrates that proficient readers question not only themselves, but the author’s intent as well.

Making and verifying predictions

Stopping periodically to predict what might happen next helps children make connections between their prior knowledge and new information in the story.

Using mental imagery and visualization

Good readers construct mental images as they read a text. By using prior knowledge and background experiences, readers connect the author’s writing with a personal picture.

Monitoring comprehension

Proficient readers know when they understand what they read and when they do not, and are able to adjust their reading accordingly. A young child may say, I don’t understand what this means. This shows that she is thinking about her reading.

Recognizing story structure

Understanding how a story is organized helps readers construct meaning. Story structure includes setting, characters, plot, and theme.

The tutor’s role

Pearson and Duke (2002) outline the components of effective comprehension lessons. When you work on a comprehension strategy with your tutee, be sure to:

- Provide an explicit description of the strategy and when it should be used

- Model the strategy

- Collaboratively use the strategy in action

- Guide your tutee in practice using the strategy

- Allow the student to use the strategy

- independently

Activating prior knowledge

Tina, the tutor, invites her student, Allison, to read the title of the book, M&M and the Bad News Babies, and then preview the book.

Tina: What does the title tell you about the story?

Allison: It’s about babies who get into trouble.

Tina: Let’s take a look at the first chapter and see what we can find out.

Allison: Look, they have a fish tank. I have fish, too. My fish live in a fish bowl, not a big tank. (Allison points to the picture of the tank on the page.)

Tina continues to preview the first chapter with Allison. They notice pictures of a mother dropping off two young children and a lively discussion about babysitting ensues. She then explicitly explains the strategy:

Tina: Allison, you are doing exactly what good readers do before they read. Good readers preview the book and think about what they already know about the topic. As we continue to read, keep in mind what you know about babysitting and doing chores. This may help you understand the story.

Why it’s important

Good readers make use of their prior knowledge and experiences to help them understand what they are reading. When a student activates her prior knowledge, the resulting connection provides a framework for any new information she will learn while reading (Graves, Juel, & Graves, 1998). This also helps ensure that the reader will remember the text after reading.

How to support your student

Before your student reads, preview the text and help her make a connection between what she already knows and the new text.

- Page through the book and ask students what they already know about the topic, broad concept, author, or genre. For example, Tina learns that Allison has a fish tank, like the characters in the story.

- Draw the student’s attention to key vocabulary or phrases. Tina draws Allison’s attention to topic words such as fish tank, babysitting, and twins.

- Talk about print and text features and the way the text is organized. For example, Tina points out that the text is divided into four chapters.

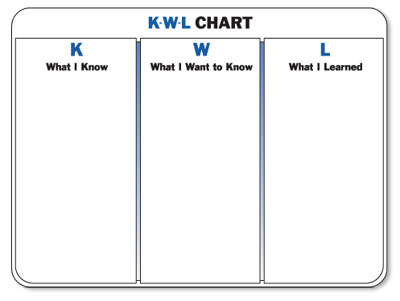

Another strategy for activating prior knowledge:K-W-L Chart

In addition to previewing the book with Allison, Tina decides to use a K-W-L chart (an example follows) as a way to explain the strategy further. K-W-L charts are especially helpful with nonfiction or expository text.

Before reading, draw a K-W-L chart like the one below on a sheet of paper.

What I Know

In the K column, list what the child already knows about the topic. If necessary, model a response to get the conversation started.

What I Want To Know

Then point to the W column and ask the student what he would like to learn by reading the text. Write responses in the form of questions. Use the questions to help set a purpose for reading.

What I Learned

While reading, turn the student’s attention to the W column. As he discovers the answers to his questions, record them and any new learnings in the L column. After reading, help your student summarize the text using all three columns.

Answering and generating questions

Before beginning the next session with Allison, Tina invites her to talk about what they read last time.

Tina: Do you remember what was happening when we read last week?

Allison: (Pauses) Well, they had to babysit. The mom left the babies.

Tina: Right. How do you think Mandy and Mimi felt about that?

Allison: Well, it didn’t really seem like they wanted to babysit. But they did it anyhow.

Tina: I wonder why they decided to do it. Do you have any ideas?

Allison: (Silence.)

Tina: I’m going to reread the section. Listen to find out why the girls decided to babysit the twins. (Reads through the line, “I’d pay you,” offered Mrs. Green.)

Allison: That’s right! They did it to get money to buy fish.

Why it’s important

Good readers ask questions before, during, and after reading. Asking, reflecting on, and answering questions enhances understanding. Encouraging students to ask themselves questions about the text will help them improve their comprehension of the story as well as recall selected elements.

Answering the questions tutors pose and generating their own questions helps children get more out of reading (Armbruster et al., 2001).Questioning helps children:

- Understand the purpose for reading

- Focus their attention on what they are to learn

- Think actively as they read

- Monitor their comprehension

- Review content and relate what they have learned to what they already know

When children ask their own questions about text, they become more aware of their level of comprehension (Armbruster et al., 2001).

How to support your student

To support their learning, you can:

- Ask open-ended questions that help students think actively about text

- Share your own questions as you read together

- Help students find clues in the text or use information they already have in their heads to answer questions

- Invite children to keep track of their questions by telling you or by writing them into a notebook or on a sheet of paper

Making and verifying predictions

After reading the first two chapters, Tina pauses to model how to make predictions, or good guesses, about the story.

Tina: Allison, let’s think about what might happen next in the story. What kind of a contest could they have?

Allison: I don’t know. Something else is going to happen with the babies. Maybe they will have a race with the babies — a crawling race.

Tina: (Writes down Allison’s two predictions.) Using clues from the story to think about what might happen next is called making predictions or very good guesses. Good readers think about what can happen in a story and then read to find out if their prediction was correct. People who read a lot are constantly making predictions. Let’s read the next two pages to see how the story matches up with your predictions.

Allison: Great, let’s see which one will win!

Why it’s important

Good readers make and confirm predictions when they form a connection between prior knowledge and new information in the text. Proficient readers have learned how to make informed predictions about what they read, read to confirm those predictions, and revise or make new predictions based on what they find out.

How to support your student

Proficient readers use this strategy before and as they read. Ways to help your tutee make and verify predictions include:

- Before reading, model how to use all available information (e.g., title of the book, prior knowledge, genre, author) to make a prediction:

- What clues about the story does the title provide?

- What does the illustration on the cover make you think of?

- Is this a real or make-believe story?

- How can you tell?

- Remind your tutee that many predictions may be wrong and that’s okay As your tutee reads, prompt her to confirm, revise, and make new predictions

- After reading, review and evaluate predictions made before and during reading

Using mental imagery and visualization

Allison comes to the point in the story when the girls realize the twins are missing.

Tina: Allison, one of the strategies readers useto help them really understand a story is making pictures in their minds. It’s called visualization. Try to visualize where the twins might be.

Allison: I can see them looking at the fish tank.

Tina: Keep going, what are they doing?

Allison: Well, they have to climb up to get a good look. Oops! They knock it over. The yellow stones are rolling everywhere…

Tina:You’re doing a good job of seeing things that are suggested by the story. Visualizing while you read is important. It’s like making a movie of the story in your mind.

Why it’s important

Visualization is a type of inference, or informed guess, about the text. Readers make a visual representation in their minds of what they read. By using prior knowledge and background experiences, readers connect the author’s writing with a personal picture. Through guided visualization, students learn how to create mental pictures as they read.

How to support your student

To practice visualization, invite your student to listen carefully as you suggest some things he is going to see in his mind. Then describe an everyday object — one that is not within view — such as an animal, something to eat, a piece of sports equipment, or an article of clothing. Give the student a few moments to form an image in his mind. Then invite him to name and describe more details, such as color, size, shape, and smell. Vary this activity by allowing the student to choose the subject of the visualization himself.

Use guided visualization either to prepare students for reading or to deepen understanding as they read. For example, have your student reread a passage from a book that describes something that is not pictured. You might say, The sentence that reads, “My mother is downstairs fixing her bike, said Mandy,” leads me to picture a mother wearing jeans and sneakers working to fix a flat bike tire. What do you see?

As your student reads, pause and monitor his mental images. Ask leading questions like:

- What sentences helped you make your mental picture?

- Were your images of the characters the same or did they change? Why?

- Did making your mental picture give you any new ideas or questions about the story?

Monitoring comprehension

It becomes clear that Allison misunderstood a part of the story, M&M and the Bad News Babies. The tex treads, Then they made silly faces at each other. This silly faces looked just like two babies sucking on bottles.Under the text is an illustration of the two girls. Allison looks at the picture and thinks that the picture shows the two girls sticking out their tongues at each other.

Allison: They look like they’re angry but that wouldn’t make sense.

Tina: Think about what you should do when you come to a point in a story where something doesn’t make sense.

Allison: (Rereads the text and finds the word silly.) Oh, I see. This word is “silly.” They are making a silly fish face.

Tina: Does the story make sense now?

Allison: Yes, because the faces look like babies sucking a bottle.

Why it’s important

Good readers monitor their comprehension while poor readers are less likely to do so (Simmons & Kameenui, 1998). Beginning readers are also less likely to use strategies to keep their reading on track (Paris & Oka, 1986).

How to support your student

Tutoring techniques for teaching and developing self-monitoring include stopping and summarizing, clarifying, making predictions, and asking questions. Questions should be open-ended and thoughtful. Teaching children to monitor their comprehension helps them:

- Be aware of what they do understand

- Identify what they do not understand

- Use appropriate “fix-up” strategies to resolve problems in comprehension

Recognizing story structure

After reading M & M and the Bad News Babies, Tina and Allison flip back through the book to better understand what happened first, next, and last in the story.

Tina: (Writes the words Beginning, Middle, and Ending onto a sheet of paper.) Allison, let’s think back to the beginning of the story. Wha thappened first?

Allison: M and M were fixing up an old fish tank.

Tina: Good, then what happened next?

Allison: The neighbor, I think her name is Mrs. Green, knocked on their door. (Allison turns to the part of the book to confirm the neighbor’s name.) Yup, her name is Mrs. Green. Mrs. Green came by and asked M and M to babysit the twins.

Tina: Anything else important happen?

Allison: The babies got into a lot of trouble.They wrecked the plants and comic books. The girls thought the babies wrecked their fish tank, but they didn’t.

Tina: What happened at the end of the story?

Allison: The girls used their babysitting money to buy fish. They named the fish after the two twins.

Why it’s important

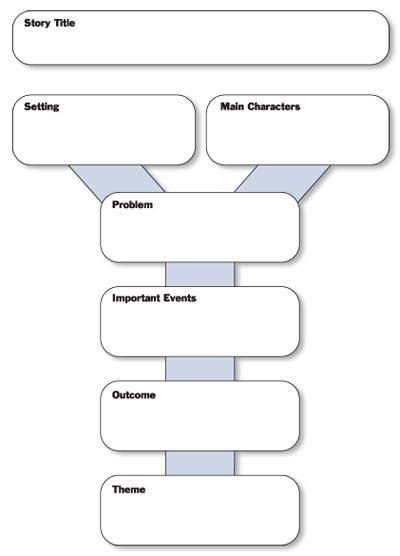

Most narrative stories are organized around a set of elements called story grammar or a story map. Learning about the structure of stories provides readers with a schema they can use when reading or listening to a new story or writing a story on their own. Most children’s stories are written using the following elements:

Setting

The setting of a story tells when and where the story takes place. Some stories have specific settings, while others occur at an indefinite time or place. Sometimes, the setting changes within the story.

Characters

Characters are the people, animals, and other individuals that populate a story. The main character is sometimes called the protagonist and generally drives the plot. The rival is called the antagonist.

Plot

The plot of a story tells what happened. It is the action of the story and gives it a beginning, middle, and ending. In general the plot consists of the following:

- A problem that the main character must solve

- The steps the character takes to solve it

- The resolution of the problem

- How the story ends

Theme

The theme is the big idea that the author wants the reader to understand. Often the conclusion of the story reveals the theme.

How to support your student

In addition to talking about and modeling thinking about what happened first, next, and last in the story, use a story map to help children understand the elements of story structure. See the Story Map below for an example.

Conclusion

As we think back on Tina and Allison, we realize that helping students become active, strategic readers requires working with them on key comprehension strategies while fostering a love of reading. The strategies presented in this article encourage children to develop their metacognition, or to think about their own thinking while they read.

Learning to read actively and purposefully helps children become proficient readers and prevents later reading difficulties. Your work with these strategies includes direct explanation, modeling, guided practice, and independent application.

As a tutor, your work also includes modeling a love of reading and reading often. Remember, children need lots of experiences with good books and an environment that supports taking risks as readers.

Gibson, A. (2004). Reading For Meaning: Tutoring Elementary Students To Enhance Comprehension. From The Tutor Newsletter, Spring 2004, 1-12. Portland, OR: LEARNS at the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.