Biography

Jewell Parker Rhodes has always loved reading and writing stories. Born and raised in Manchester, a largely African-American neighborhood on the North Side of Pittsburgh, she was a voracious reader as a child.

She began college as a dance major, but when she discovered there were novels by African Americans, for African Americans, she knew she wanted to be an author. She has written novels for adults, two writing guides, and a memoir, but writing for children has always been her dream.

Jewell’s children’s books include The New York Times bestseller Ghost Boys and the Louisiana Girls Trilogy of Ninth Ward, Sugar, and Bayou Magic. When she’s not writing, Jewell visits schools to talk about her books with the kids who read them. She also teaches writing at Arizona State University, where she is the Piper Endowed Chair and Founding Artistic Director of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing.

Jewell earned a Master’s degree and a Doctor of Arts from Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh. She lives with her husband in San Jose, California, along with two toy sheepdogs and a cat. She’s the proud mother of a daughter and a son, and the very proud grandmother of a young granddaughter.

Visit the official Jewell Parker Rhodes website for more information, including teaching guides for Jewell’s books. Follow Jewell on Twitter and Facebook.

Books by this author

Visiting her grandmother in Louisiana, Maddy realizes she may be only the sibling to carry on her family’s magical legacy. And when a disastrous oil leak threatens the bayou, she knows she may also be the only one who can help. A coming-of-age tale rich with folk magic. See the two other two books in the Louisiana Girls Trilogy, Ninth Ward (opens in a new window) and Sugar (opens in a new window).

Bayou Magic

Donte and his brother are biracial; their mother is Black, their father is white. They attend the same wealthy suburban school but have very different experiences there. Donte is dark-skinned but his brother appears white. How Donte gains a sense of sense of self and beats the bully at his own game is compelling and timely.

Black Brother, Black Brother

Twelve-year-old Jerome is shot by a police officer who mistakes his toy gun for a real threat. As a ghost, he observes the devastation that’s been unleashed on his family and community. Jerome meets another ghost: Emmett Till, a boy from a very different time but similar circumstances. Emmett takes Jerome on a journey towards recognizing how historical racism may have led to the events that ended his life.

Ghost Boys

Orphaned at birth, Lanesha has second sight, giving her the ability to see her mother’s ghost. She also senses an impending storm which will devastate New Orleans and that her grandmother won’t survive. How Lanesha stays alive and the people she meets and helps along the way — plus a bit of magic realism — create a compelling read. See the two other two books in the Louisiana Girls Trilogy, Bayou Magic (opens in a new window) and Sugar (opens in a new window).

Ninth Ward

Through the curious, joyful eyes of 10-year-old Sugar, readers experience life on a Louisiana sugar plantation after Emancipation. Issues arise when Chinese workers are brought in to help harvest the cane. Sugar soon realizes that she must be the one to bridge the cultural gap and bring the community together. See the two other two books in the Louisiana Girls Trilogy, Ninth Ward (opens in a new window) and Bayou Magic (opens in a new window).

Sugar

When her fifth-grade teacher hints that a series of lessons about home and community will culminate with one big answer about two tall towers once visible outside their classroom window, Dèja can’t help but feel confused. She sets off on a journey of discovery, with new friends Ben and Sabeen by her side. A story about young people who weren’t alive to witness 9/11, but begin to realize how much it colors their every day.

Towers Falling

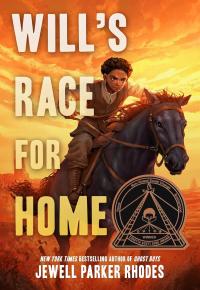

An adventure story about a son and his father who set out to win land during the Oklahoma Land Rush — if they can survive the journey. It’s 1889, barely twenty-five years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and a young Black family is tired of working on land they don’t get to own.

So when Will and his father hear about an upcoming land rush, they set out on a journey from Texas to Oklahoma, racing thousands of others to the place where land is free — if they can get to it fast enough. But the journey isn’t easy — the terrain is rough, the bandits are brutal, and every interaction carries a heavy undercurrent of danger. And then there’s the stranger they encounter and befriend: a mysterious soldier named Caesar, whose Union emblem brings more attention and more trouble than any of them need. All three are propelled by the promise of something long denied to them: freedom, land ownership, and a place to call home — but is a strong will enough to get them there?

Will’s Race for Home

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Being Brave

Themed Booklist