Biography

The daughter of an American military judge and a Scottish psychiatric social worker, Julianne Moore was born at Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina in 1960. Growing up as an “army brat,” she lived in Germany and all over the U.S., moving 23 times — and always turning to books to nourish her love of storytelling. Moore graduated in 1983 from Boston University with Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in acting from the School of the Performing Arts. After graduation, Julianne moved to New York and started working in theater, and within a few years joined the cast of the popular soap opera As the World Turns. She began to appear in film in the early 1990s.

Moore has received widespread acclaim for her work as an actor on television, stage, and film, including multiple nominations for the Oscar, Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and Screen Actors Guild Awards. Moore has had memorable roles in a wide range of films such as The Big Lebowski, Magnolia, Far from Heaven, and The Kids Are All Right.

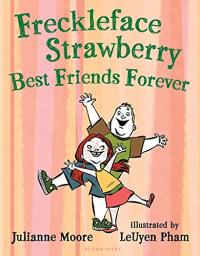

In 2007, Moore made her literary debut with the publication of Freckleface Strawberry, a children’s book based on her experiences as a red-headed, frecklefaced child. In 2009, Moore followed up with a second children’s book titled Freckleface Strawberry and the Dodgeball Bully and in 2011 she published the third book in the series, Freckleface Strawberry: Best Friends Forever.

Moore lives with her husband (screenwriter Bart Freundlich) and two children in New York City. In addition to her acting and writing, she is an Artist Ambassador for Save the Children’s rural literacy program.

Books by this author

Typical in most ways but teased because of her freckles, 7-year-old Helen has red hair and lots of freckles unlike her family. When teased by other kids, she tries to get rid of her freckles in lots of ways but keeps her nickname instead.

Freckleface Strawberry

Freckleface Strawberry and the Dodgeball Bully