About Kekla Magoon

Kekla Magoon is the award-winning author of many novels and nonfiction books for young readers, including The Season of Styx Malone, The Highest Tribute: Thurgood Marshall’s Life, Leadership and Legacy, She Persisted: Ruby Bridges, and the Robyn Hoodlum Adventure series. Kekla has also written novels for teen readers, including The Rock and the River, How It Went Down, X: A Novel, and Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People.

She has received the Margaret A. Edwards Award, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, the John Steptoe New Talent Award, three Coretta Scott King Honors, the Walter Award Honor, an NAACP Image Award, and a National Book Award Finalist (Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People).

Kekla grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana. She learned to read at the age of two. Her mom read lots of books to her, and took her to the library every week so she could read and read and read. Kekla made a habit of checking out as many paperbacks as she could carry! She wrote her first novel when she was in high school.

Kekla is biracial — her mom is white and her dad is black. Her mom grew up in the U.S., but her ancestors came from Holland, Scotland, and maybe elsewhere in Europe. Her dad grew up in Cameroon, a country in western Africa. When Kekla was very young, she lived with her parents in Cameroon for several years. Getting to have experiences like that makes it great to be biracial.

Kekla graduated from Northwestern University, where she majored in History, with a concentration in the History of Africa and the Middle East. Today, Kekla lives and writes in Vermont. She is a full time author, speaker, and writing teacher. She travels to schools and libraries around the country to talk about her books with young readers, which is a lot of fun. She teaches at Vermont College of Fine Arts where she mentors other writers who also want to create books for young readers. Kekla also serves on the Writers’ Council for the National Writing Project.

NOTE: This brief biography is excerpted from Kekla’s website (opens in a new window). To learn more about Kekla’s books, discussion guides, Reader’s Theater scripts, classroom activities, and more, visit Kekla Magoon’s official website (opens in a new window).

Kekla has also written acclaimed novels and nonfiction for teen readers, including Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People, The Rock and the River, and How It Went Down. To hear Kekla talk about her YA books, visit our sister site, AdLit › (opens in a new window)

Books by this author

Set in the modern-day suburbs of Las Vegas, biracial sixth-grader Ella Cartwright finds herself caught between two worlds. She is drawn to the popular new boy, Bailey — the only other black student in the school — but also loyal to her best friend, Z, a geeky boy whose social status, like hers, is bottom-rung, and with whom she has shared an incomparable friendship. A relationship with Bailey means a chance at popularity for Ella, but Z is far too weird to ever be accepted by his classmates. When push comes to shove, where will Ella turn for real friendship?

Camo Girl

Chester likes his routines, but his new friend is the complete opposite. Nonetheless, the pair work together to solve the riddle behind the mysterious notes that Chester thinks are from his father — all while dealing with a bully and trying to prevent his mother from worrying. Likeable characters and an engaging mystery fill this satisfying novel.

Chester Keene Cracks the Code

When 16-year-old Tariq Johnson dies from two gunshot wounds, his community is thrown into an uproar. Tariq was black. The shooter, Jack Franklin, is white. In the aftermath of Tariq’s death, everyone has something to say, but no two accounts of the events line up. By the day, new twists and turns further obscure the truth. Tariq’s friends family and community struggle to make sense of the tragedy, and of the hole left behind when a life is cut short. In their own words, they grapple for a way to say with certainty: This is how it went down.

How It Went Down

The night her parents disappear, 12-year-old Robyn Loxley must learn to fend for herself. Her home, Nott City, has been taken over by a harsh governor, Ignomus Crown. After fleeing for her life, Robyn has no choice but to join a band of strangers — misfit kids, each with their own special talent for mischief. Setting out to right the wrongs of Crown’s merciless government, they take their outlaw status in stride. But Robyn can’t rest until she finds her parents. This is the first book in the Robyn Hoodlum Adventure series (see Rebellion of Thieves (opens in a new window) and Reign of Outlaws (opens in a new window)).

Shadows of Sherwood

As a first grader, Ruby Bridges was the first Black student to integrate William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana. This was no easy task, especially for a six-year-old. Ruby’s bravery and perseverance inspired children and adults alike to fight for equality and social justice. (From the She Persisted series)

She Persisted: Ruby Bridges

Born in Baltimore (MD), Thurgood Marshall would grow up to be one of the most powerful forces in rights for Black citizens. Clearly illustrated with an accessible text, Marshall’s life and legacy are presented, complete with a timeline, major cases, and more.

The Highest Tribute: Thurgood Marshall’s life, Leadership, and Legacy

A young Black boy wrestles with conflicting notions of revolution and family loyalty as he becomes involved with the Black Panthers in 1968 Chicago. Thirteen-year-old Sam Childs finds himself caught between his father (a well-known civil rights leader) and his older brother, Stick, who joins the Black Panther Party. When escalating racial tensions throw Sam’s community into turmoil, he faces a difficult decision. Will Sam choose to follow his father, or his brother? His mind, or his heart? The rock, or the river? (For middle grade readers and older.)

The Rock and the River

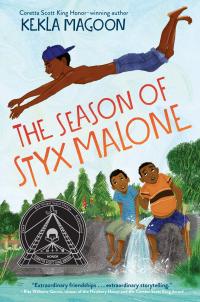

Caleb Franklin and his big brother Bobby Gene are excited to have adventures in the woods behind their house. But Caleb dreams of venturing beyond their ordinary small town. Then Caleb and Bobby Gene meet new neighbor Styx Malone. Styx is sixteen and oozes cool — and he leads the brothers on a one-thing-leads-to-another adventure in which friendships are forged and loyalties are tested.

The Season of Styx Malone

Cowritten by Malcolm X’s daughter, this fictionalized biography follows the formative years of Malcolm X, from his childhood to his imprisonment for theft at age twenty, when he found the faith that would lead him to forge a new path and command a voice that still resonates today.

X: A Novel

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2022

Themed Booklist