Biography

Mary Ann Hoberman was born in 1930 in Stamford, Connecticut. In high school, she wrote for the school newspaper and was a yearbook editor. She and her husband, architect and artist Norman Hoberman, raised four children in their Connecticut home. Hoberman has taught writing and literature to students at all levels — elementary school through college. But ever since her first book All My Shoes Come in Twos was published in 1957 (inspired by her own children and illustrated by her husband), Hoberman’s primary focus has been writing for young people.

Hoberman’s most recent books include the 2009 poetry anthology The Tree that Time Built (co-edited with Linda Winston), and Hoberman’s first novel Strawberry Hill, also published in 2009. The Tree that Time Built is filled with poems (some penned by Hoberman) and commentary that reveal the deep connections between science and poetry.

Through 50+ years of writing, Hoberman’s work remains consistent in its craft, simplicity, playful use of language, and sensitivity to children’s deepest feelings. About poetry, she says, “poetry is fun and you can go from fun and light verse and word play and you can segue very nicely into far more serious ideas and use of words and you bring the children with you.”

Books by this author

A House Is a House for Me

All Kinds of Families

Fathers, Mothers, Sisters, Brothers: A Collection of Family Poems

I Know and Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly

An imaginative child shares her pleasure in old clothing, repurposing them and finding joy in imagining the history, mystery surrounding them. Soft, expressive illustrations accompany the lively rhythmic, rhyming text.

I Like Old Clothes

Seven Silly Eaters

Ten year old Allie Sherman resists her family’s move until she learns that they will live on Strawberry Hill. It is on this intriguing sounding street that Allie finds a friend, confronts racism, and comes to appreciate her family. Set during the Great Depression, this nostalgic novel continues to ring true.

Strawberry Hill

The Llama Who Had No Pajamas

Clearly organized with lucid introductions to each section as well as for select poems, this handsome anthology includes a range of poems and poets for an evocative, informative, and often inspiring look at science and nature.

The Tree that Time Built: A Celebration of Nature, Science and Imagination

Whose Garden Is It?

Humorous illustration and color-coded, rhyming text present retellings of familiar fables that include the morals (though with a light touch). Newly independent readers will have fun reading the short, snappy text with a second reader as they enjoy the cheery visuals.

You Read to Me, I’ll Read to You: Very Short Fables to Read Together

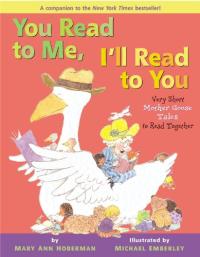

Take-offs of Mother Goose rhymes are the subject in this third read aloud/read together book. Color-coded text indicates when each of two readers should read alone or together. Comic cartoon-like illustrations romp across and through each double page poetic tale.

You Read to Me, I’ll Read to You: Very Short Mother Goose Tales to Read Together

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Arts and Crafts for Summer Fun

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2004

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2005

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2009

Themed Booklist