Biography

A former actress, Emma Walton Hamilton worked in theater, film, and television for 10 years before turning her attention to directing, producing, educating and writing. She is one of the founders of Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor, New York. She served as co-artistic director for thirteen years and now focuses her energies on the theatre’s education and young audiences programs. Emma directs the Young American Writers Project, an inter-disciplinary writing program for middle and high school students.

Emma is also the editorial director for The Julie Andrews Collection, a publishing program dedicated to quality books for young readers that nurture the imagination and celebrate a sense of wonder. In addition to writing and editing children’s books, Emma writes articles for magazines, newspapers, e-zines, and periodicals. Her most recent book is Raising Bookworms: Getting Kids Reading for Pleasure and Empowerment.

Emma travels frequently across the country, speaking to groups about the value of, and synergy between, the arts and literacy. She lives in Sag Harbor, NY, with her husband, producer/actor Steve Hamilton and their two children, Sam and Hope.

Books by this author

The murder of a young knight, a white wolfhound, and a faithful page in medieval France all come together to create a fast-paced, gripping mystery.

Dragon: Hound of Honor

Before the barn can be razed on Merryhill Farm, Charlie and his grandfather restore the old dump truck that Charlie so loves. Not only does Dumpy the Dumptruck prove his worth, readers will appreciate that old isn’t always bad!

Dumpy the Dumptruck

Theater mice perform in a space just out of human sight in a venerable old New York theater. Alas! The leading rodent taken to Brooklyn before she performs in the final play before the theater is destroyed. Humor abounds in this satisfying tale.

Great American Mousical

A range of poetic styles, some rooted in the authors’ family, are shared in this handsome, easily accessible collection. Attractive illustrations are sprinkled throughout, building the joy when the poems are shared, even when listening to the beautifully read CD.

Julie Andrews’ Collection of Poems, Songs, and Lullabies

This book offers creative strategies, tips, and activities to help young people discover — or rediscover — the joy and empowerment of reading.

Raising Bookworms: Getting Kids Reading for Pleasure and Empowerment

Simeon loves a noblewoman from afar and seeks to find the music from deep inside him. His quest turns to despair until a series of events allow him to discover his real worth. Well told and strikingly illustrated, this modern fable resonates with readers.

Simeon’s Gift

Children learn from their mothers and mothers learn from their children. Photographs from the authors’ extended family combine with gentle language to convey universal emotions and universal wisdom.

Thanks to You: Wisdom from Mother & Child

Geraldine is a princess, a fairy princess with a crown and lots of sparkle. Her life as a fairy princess is filled with ballet (where she sparkles a lot), school, and with friends. Muted illustrations and an innocent narration combine to present a loving family whose child is indeed a very fairy princess.

The Very Fairy Princess

There’s something for every member of the family in this carefully selected and expertly performed poetry by a well-known mother-daughter team.

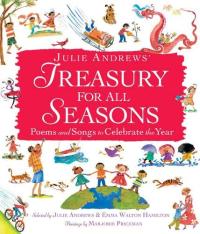

Treasury for All Seasons: Poems and Songs to Celebrate the Year

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Holiday Buying Guide 2009

Themed Booklist

Our Favorite Audiobooks

Themed Booklist

Reading Motivation and Reading Aloud

Themed Booklist