The first six clips you’ll find here were recorded at Jeff Kinney’s bookstore (An Unlikely Story) in Plainville, MA. In October 2017, five award-winning authors for young people — Jack Gantos, Jeff Kinney, Jarrett Krosoczka, Jon Scieszka, and Gene Luen Yang — gathered for a funny and insightful panel discussion about how to motivate boys (and any reluctant readers) to read more. Watch the panel discussion: How to Get and Keep Boys Reading.

The rest of our interview with Jack was recorded earlier in our WETA studio.

Biography

Jack Gantos was born in Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania. His parents moved so often that he attended 10 different schools between kindergarten and twelfth grade. The Gantos family rented a variety of homes in Pennsylvania, Florida, North Carolina, and the Caribbean. Jack spent his senior year of high school in Florida after his parents had already moved to Puerto Rico. During that year, Gantos worked at a grocery store, bought a car, and lived in an old motel run by Davey Crocket’s great-great granddaughter.

After finishing high school, Gantos made a last-minute decision not to attend the University of Florida. Instead, he moved to the Virgin Islands to work on construction projects with his father. While hanging out in a bar one day, Gantos was approached by a man with an offer he couldn’t refuse: sail a small boat from the Caribbean Sea to the United States for $10,000. That much money would pay for four years of college and more, Gantos reasoned at the time. The only catch was that the boat was filled with 2,000 pounds of hashish.

Little did Gantos know when he ran aground on the New Jersey shore, the FBI and the U.S. military had been tracking his boat. At the age of 20, he was sent to prison. During his 18 months behind bars, Jack Gantos read, wrote, and vowed to turn his life around. After getting out of prison, he moved to Boston, enrolled in college, and began writing children’s books. Within two years he sold his first children’s book manuscript about a rotten red cat named Ralph.

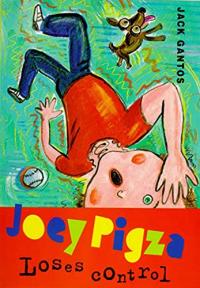

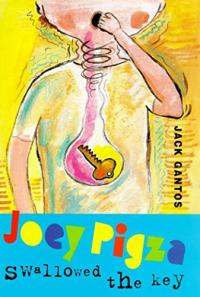

Over time Jack Gantos established himself as an award-winning author of a wide variety of books. He wrote picture books for young children. He wrote chapter books for middle-grade readers. In 2001 Joey Pigza Loses Control, a book about a boy with ADHD, received a prestigious Newbery Honor. By 2002 Jack Gantos finally felt comfortable publishing a book about the time he went to prison. This nonfiction book for teens, Hole in My Life, has won numerous awards and reached many troubled teenage boys. In addition to writing, Jack Gantos speaks to young people in classrooms, libraries, and prisons.

Today he lives with his wife and daughter in Boston, Massachusetts.

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

Books About Kids Who Find Reading Hard

Themed Booklist

Newbery Medal Winners

Themed Booklist