Biography

Rudine Sims Bishop is Professor Emerita of Education at The Ohio State University, where she has taught courses on children’s literature. Her books include Shadow and Substance: Afro-American Experience in Contemporary Children’s Fiction (1982), Presenting Walter Dean Myers (1990), Kaleidoscope: A Multicultural Booklist for Grades K–8 (1994), Wonders: The Best Children’s Poems of Effie Lee Newsome (1999), and Free within Ourselves: The Development of African American Children’s Literature (2007). In Free Within Ourselves, Dr. Bishop takes the reader on a historical journey, from the earliest works written about African American children (W.E.B. DuBois’ The Brownies Book) to John Steptoe’s Stevie to the contemporary award-winning writer Christopher Paul Curtis and his Bud, Not Buddy, winner of both the Newbery Medal and the Coretta Scott King Author Award.

Dr. Bishop has been recognized with numerous awards, including the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Outstanding Educator in English Language Arts Award and the Arbuthnot Award, and has been on the selection committees for both the Caldecott and Newbery Medals. Her life’s work has been built on the foundation “that all American children, but especially Black children, need to learn the story of African Americans’ struggle on the journey.” Read her essay Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.

In 2017, Dr. Bishop was awarded the Coretta Scott King – Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement. The award pays tribute to the quality and magnitude of beloved children’s author Virginia Hamilton.

Books by this author

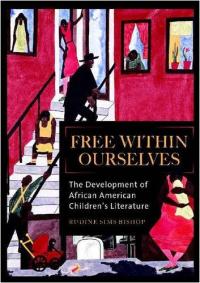

Bishop guides you from important early works for African American children such as W.E.B. DuBois’ The Brownies Book, to the 1969 publication of John Steptoe’s Stevie — the breakthrough modern African American picture book — to recent young adult fiction such as Christopher Paul Curtis’ popular Bud Not Buddy, winner of both the Coretta Scott King Author Award and the Newbery Medal. All along, her energetic chronicle brings to life the crucial figures who have contributed to the rise of African American children’s literature and delves deep into the plot, characters, and themes of their most popular and teachable works. The result is an unparalleled treasury of ideas and information for teaching with African American children’s literature.

Free Within Ourselves: The Development of African American Children’s Literature

This seminal work identifies and addresses key issues that have become touchstones in the study of African-American children’s literature. It provides classroom teachers, librarians, and teacher educators in the field of children’s literature with information to build stronger multicultural collections for libraries and classroom study. The first chapter of the work places contemporary realistic fiction about Afro-Americans in a sociocultural and historical context, while the second chapter discusses the “social conscience” books that are written primarily to help whites know the condition of blacks in the United States. The third chapter reviews “melting pot” books that were written for both blacks and whites on the assumption that both groups need to be informed that nonwhite children are exactly like other American children — except for their skin color. The fourth chapter examines “culturally conscious” books that were written for Afro-American readers and that attempt to reflect both the uniqueness and the universal humaneness of the African-American experience from the perspective of an African-American child or family. The fifth chapter presents a brief overview of the work of five African-American writers who have made significant contributions to children’s fiction since 1965, and the final chapter summarizes the current status of children’s fiction about African Americans and suggests some areas yet to be covered in fictional works.