Kelly Barnhill is the author of fantasy novels for children, including The Girl Who Drank the Moon (winner of the 2017 Newbery Medal), The Witch’s Boy, Iron Hearted Violet, and The Mostly True Story of Jack. Barnhill has also written many nonfiction books for children published by Capstone Press, including Sewers and the Rats That Love Them and Monsters of the Deep.

She studied creative writing as an undergraduate, and before finding success as an author Barnhill worked for the National Park Service and was trained as a volunteer firefighter.

Barnhill has received writing fellowships from the Jerome Foundation and the Minnesota State Arts Board and was a 2015 McKnight Writing Fellow in Children’s Literature. She is the winner of the Parents Choice Gold Award, the Texas Library Association Bluebonnet award, and a Charlotte Huck Honor. She also was a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, the Andre Norton Award and the PEN/USA literary prize.

Barnhill is a graduate of St. Catherine University in St. Paul. She lives in Minneapolis with her architect husband and their three children.

To learn more (and to find out about school and Skype visits) visit Kelly Barnhill’s website.

Books by this author

Princess Violet is plain, reckless, and possibly too clever for her own good. Particularly when it comes to telling stories. One day she and her best friend, Demetrius, stumble upon a hidden room and find a peculiar book. A forbidden book. A different kind of fairy tale, about the power of stories, our belief in them, and how one enchanted tale changed the course of an entire kingdom.

Iron Hearted Violet

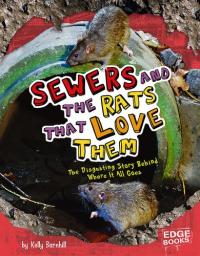

Are you ready to go behind the scenes of our amazing sanitation system? From the history of toilets to the mystery of tap water, each book reveals what goes on after the flush and after the trash has been taken out.

Sewers and the Rats That Love Them

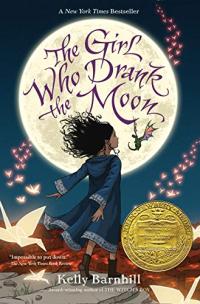

An young girl raised by a witch, a swamp monster, and a Perfectly Tiny Dragon, must unlock the powerful magic buried deep inside her. Every year, the people of the Protectorate leave a baby as an offering to the witch who lives in the forest. They hope this sacrifice will keep her from terrorizing their town. But the witch in the forest, Xan, is kind and gentle. The swiftly paced plot draws many threads together to form a web of characters, magic, and interwoven lives. (Winner of the 2017 Newbery Medal)

The Girl Who Drank the Moon

An eerie tale of magic and friendship. When Jack is sent to Hazelwood, Iowa, to live with his strange aunt and uncle, he expects a summer of boredom. Little does he know that the people of Hazelwood have been waiting for him for quite a long time.

The Mostly True Story of Jack

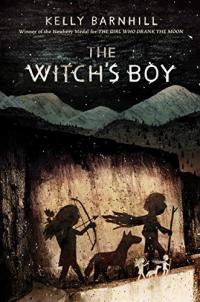

Warring nations, mysterious stone figures, and the running thread that magic is alive and dangerous all add to the gripping cnarrative of two children who find strength and ingenuity from being pushed out of their comfort zones. Áine, the daughter of the Bandit King, is haunted by her mother’s last words: “The wrong boy will save your life, and you will save his.”