Biography

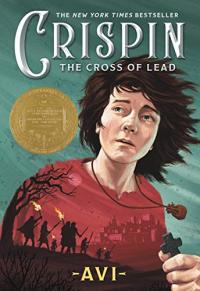

Avi has been writing for nearly fifty years. It is something he loves to do and something he tries to do every day. After publishing fifty books and receiving two Newbery Honors, Avi won the prestigious Newbery Medal in 2003 for Crispin, a coming-of-age novel set in fourteenth century England.

Although Avi is best known for his middle grade historical fiction, he also writes popular mysteries, fantasies, adventure stories, ghost stories, and animal tales for younger readers. And, in spite of his many successes as an author, Avi acknowledges that writing is still hard work. “Not knowing what to put down for the next sentence is what my life is all about,” he says.

A writer’s life

Avi was born in New York City in 1937. He grew up in a family of readers, writers, and artists. His twin sister, who gave him the nickname “Avi” at an early age, also became a writer.

Throughout his elementary and high school years, Avi’s teachers complained that his writing was messy and careless. Avi would later find out that he had symptoms of dyslexia, which explained his poor spelling, letter reversals, and other “sloppy” work. After failing out of his first high school, Avi received special tutoring sessions one summer that inspired him to become a writer. Although Avi avoided English classes during college, he continued to read and write voraciously.

Avi originally wanted to become a Broadway playwright. But as he later acknowledged, “I spent a fair number of years writing a whole lot of bad plays.” Avi discovered the world of children’s writing only after he became a father. His first published book was a collection of stories he had invented for his oldest son.

For 25 years, Avi worked as a librarian – a career that supported both his family and his writing. Eventually, Avi’s literary success enabled him to become a full-time author. After winning Newbery Honors for The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle and Nothing But the Truth, Avi won the 2003 Newbery Medal for Crispin: A Cross of Lead.

Although writing is his passion and his profession, Avi emphasizes that family still lies at the center of his life. Now both a father and a grandfather, Avi lives with his wife in Denver, Colorado.

Find this author’s books on these booklists

Themed Booklist

From the American Revolution to a New Nation

Themed Booklist