It’s funny to be a teacher! When everyone else thinks of the “New Year” starting January 1st, teachers are getting ready to start their “third quarter.” Usually about our “half-time” (aka: Winter Vacation) I enjoy reflecting on our year so far, and how I can tweak my instruction to streamline our focus. So after the presents have been opened, traditions enjoyed, and champagne and poppers cleaned up, it’s always a good opportunity to sit back, and begin deciding where instruction needs to be strengthened.

This article focuses on an instrumental shift in the Common Core: answering questions grounded in the text.

What I am noticing in my students’ responses is a lack of “proof” that supports their answers. We are just getting into an in-depth unit on inferring and character analysis. I enjoy pairing these two, back to back, because there is an abundant amount to discover about characters, theme, and plot development through evidence that the author provides. However, I typically find, that unless explicitly taught, even my above-grade-level readers have a hard time finding the evidence, understanding how it connects to their schema, and then processing it into a constructed response. So hopefully the next bits of information will give you some ideas of teaching your students how to make fictional inferences.

Schema

We, as educators, understand that schema is all of the knowledge we have, organized and connected to itself in our brains. We begin lessons with it, use it to ground our students’ understanding, and help students to connect to new learning, we call it: prior knowledge. However, where we typically fall short, is teaching kiddos what schema is, and how they can use it in their own learning. A student’s understanding of how his brain categorizes information is a new awakening for most of my third graders. So you can bet that when I’m teaching my kiddos how to infer, they are going to struggle, because half the battle of learning how to make an inference is the understanding of, WHY we understand.

One of the first lessons I teach in third grade is about schema. We open the filing cabinet and pull out file folders and discuss how our brain organizes information in a similar fashion. Following that, we discuss how life experiences, school, reading, our families, and interests help build a larger cabinet the longer we are alive. This discussion helps students to see how their connections and familiarities to things in life, stems from their schema and experiences. For example, when I taught in Arizona, many of my students didn’t have a ton of schema about snow, or the beach, but could go on for days about cacti and scorpions in their backyard. Whereas, in Washington DC my students have trekked through inches of powder, just to get to school, and opened up newly caught crabs off the bay in Maryland, but hardly know anything about the desert. This is their schema … TEACH THEM THAT!

Finding the evidence

When students are reading, everything looks the same. The font’s the same size and color, the text is endless, and finding evidence can be like looking for a needle in a haystack … especially to a below grade level reader. So our job is to give our students strategies to FIND the evidence. Here are a few I have come across over the years, and find to be very helpful for my students.

Reading with a “pen in hand”

(Note: I am not claiming this strategy — this is all Mike Schmoker!)

Imagine you’re at a staff meeting, your principal hands you this FABULOUS article that you can’t wait to dig into! The first thing you do is grab a pen, pencil, highlighter, or anything that will help you extract important info that you want to remember! So why, when we give students a text, do we go out of our way to make sure there aren’t any pens around to write in the books.

Schmoker explains, that we, as educators, keep this very influential strategy from students, and it is IMPERATIVE that they use a writing tool when they are extracting information from text! I know, I know … you HATE it when students write in their books! But take a moment and think about what must be going through a student’s mind when he has to extract information, and everything looks the same! How are students going find, decipher, and eliminate information without a tool to help? I understand that copying the text, or dealing with writing in novels is sometimes not an option, but Post-its™ and pencils work just as well!

Related articles

- College Readiness: Reading Critically (Edutopia)

- Reading With Pen in Hand: Teaching Annotation in Close Reading (We Are Teachers)

Coding

A couple weeks ago, my students and I were reading a Washington Post article on Kepler 22B, a planet that has a few similarities to Earth. I knew that finding similarities and differences would be tricky, given the level of text and comparing paired with contrasting. So I just quickly discussed, prior to the read, that when we find a similarity to Earth, we write an “S” and when we find a difference we can mark a “D.” Do I need to tell you how easy it was for my students to write their compare-and-contrast constructed response? (That’s probably one of those pesky rhetorical questions!)

I know this example was related to an informational text, but it can work the same with a literary novel! Students just need to know HOW to label their evidence, and they’ll go at it like gangbusters! Let’s imagine you’re teaching kiddos elements of a story, you can easily provide codes such as:

S — Setting

T — Talking Characters

O — Oops! A Problem!

R — Attempts to Resolve the Problem

Y — Yes, the Problem is Solved!

Something as simple as having students draw a star where they might find evidence of an action that shows a character being vain, or brave when you teach character traits, will help students to extract information, and draw their eye to it later in order to use it in their constructed response.

The inferring begins!

So now comes the fun part! We have to teach our students to pair the schema with the evidence. Let me give you an example. There’s a book called The Stranger by Chris Van Allsburg. The book provides a GREAT way to teach how to make inferences. The gist of the story is this: there is a man, and he represents winter. The man visits a farm, and as he’s visiting there are clues in the story: the thermometer mercury drops to the bottom, when he blows on his soup there is a rush of cold air, etc. This is the evidence. Where we must connect students’ schema is their understanding that cold air is a sign of winter, a thermometer dropping means that it’s getting colder. This is their schema.

In younger grades, picture clues can draw inferences better than anything! The characters’ faces, body language, and actions are all clues — for example, are the people/animals in the picture running from a situation (scary/danger), or are they coming towards the event (happy/intriguing). You can use pictures to begin inferring in upper grades as well.

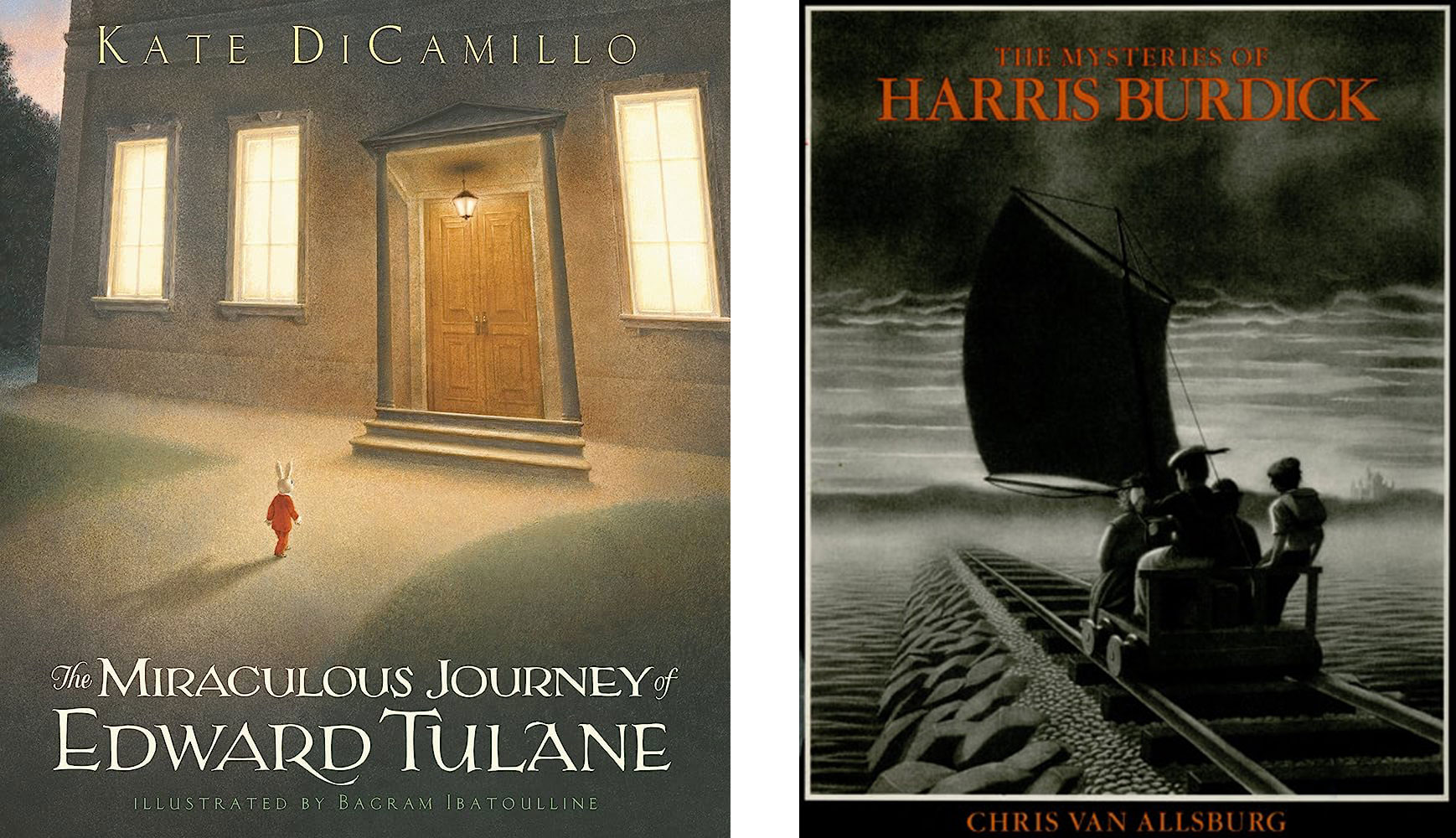

Pictures such as those in Van Allsburg’s The Mysteries of Harris Burdick help to pose questions, draw upon schema, and extract evidence from text. If you have ever read The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, there are incredible pictures to use to draw inferences.

The key is to pull evidence by asking the beginning questions, and then leading to deeper Bloom’s-based questions. How do you know? What tells you he represents winter? Explain why he doesn’t represent fall or snow? My favorite two words to use with my kiddos are: PROVE IT! It’s a challenge! Find the information, highlight it, dig deep in that text!

Asking questions that are grounded in evidence and expecting that your students answer questions that way, is a best practice. Hold your students to this expectation and challenge them to TRULY understand their schema and the way inferring connects with it in literary text.

Emily Stewart, M.Ed., is a third grade teacher at Murch Elementary, a public school in Washington, DC.