David Bowles is an award-winning writer and poet, reviewer and translator, elected to the Texas Institute of Letters in 2017. He teaches children’s and young adult literature at the University of Texas Rio Grande. Living in Texas on the border of the United States and Mexico with his family, he not only embraces his Mexican-American heritage, he explores it in his writing.

I first met David Bowles through his books for young readers. I had the opportunity to meet him in person at the 2019 Walter Dean Myers Awards program in March. (This memorable event is sponsored by We Need Diverse Books and the Library of Congress.) He not only spoke on a panel with the other honorees, but also to groups of students in separate programs. I was struck by his unique perspectives and insights — some of which he shares here.

Tell us about your background and how it led you to become interested in writing.

I grew up in a Mexican American family — led by my grandfather, Manuel Garza, and my grandmother Marie (a redheaded woman of French-Irish extraction who had taken to Mexican culture like a fish to water in her early 20s). It was Marie’s second marriage — she’d left the man who’d wedded her at 16 and come to South Texas, only fall in love with Manny. They married on the sly in Mexico two years after my father’s out-of-wedlock birth. They had three more children—my aunt Linda Garza and uncles Michael and Daniel — establishing a relatively happy border clan.

But their cuentos … oh, such dark and twisted tales! A blend of Southern Gothic and Colonial Mexican emerged from Marie’s powerful imagination, and all her children grew up to be storytellers as well. When I was a little kid, all those spooky folklore captured my mind and heart. I wanted more. My grandmother Garza — Mimi, we called her — eventually tired of my constant pleading. “Learn to read, boy,” she said at last. “Books have tons of stories. And there are thousands waiting for you on the library shelves.”

So I bugged my mom to teach me to read. She did, and by the time I was 5 years old, I was devouring books. Not many years later, I realized that this was what I wanted: to take my family’s stories and turn them into books. To evolve from storyteller to author.

What drew you to writing for children and young adults?

When I was a middle school teacher, I was in the midst of writing “the Great American Novel” (while doing my MA). But I had a group of struggling students whom I finally reached by taking the scary folktales that had thrilled me as a kid and turning them into short stories with literary devices. My students were hooked, and I realized that it was my calling.

What would you like others to know about life along the border as it gets so much attention these days?

Life here is much like it has always been. We are a tight-knit community of loving families living as best we can, seeking happiness and peace. There’s no crisis here, just people being people, falling in love, getting married, having kids, dreaming what dreams their hearts permit. Were we to be left alone, to manage our transnational community without so much interference, we’d be fine. We have systems for absorbing those who flee nightmares to the south. They fit within our neighborhoods and schools. This is no post-apocalyptic wasteland. It’s the Magic Valley.

Middle school is kind of a border — between childhood and adolescence. Can you talk about why you chose that age for your lead character, Güero?

When I started writing poems in the same voice I had used for “Border Kid,” an image began to form, then a character. I didn’t dictate his age … it just emerged organically from the process. Soon “he” was telling me about his 7th grade year, and I knew that he was 12. It was pretty magical, actually.

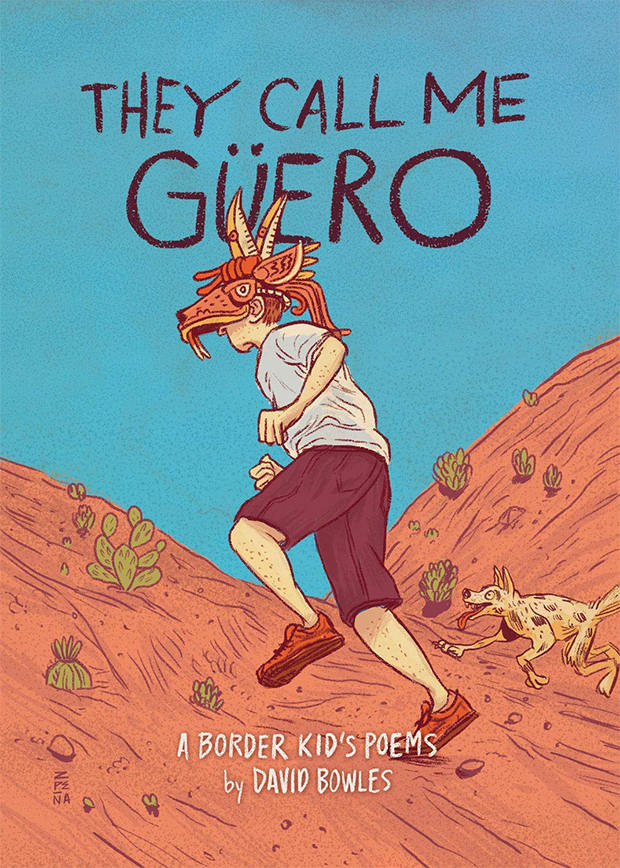

You’ve written They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems as a novel in verse. How did you come to write a novel in this form? What was your process?

The book’s genesis was the poem “Border Kid,” commissioned by Sylvia Vardell and Janet Wong for their anthology Here We Go! (put together in response to the anxiousness kids of color were feeling at Trump’s election). The speaker of the piece is a Chicano kid living on the border who goes with his dad to the little town on the Mexican side. When they’re driving back, the border fence makes the boy sad, but his dad reassures him that it cannot stop his heritage “from flowing forever, like the Río Grande itself.”

That poem got reprinted in the Journal of Children’s Literature, and when I was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters in April of 2017, it was one of the pieces I read before the members of TIL. Afterward, Bobby Byrd of Cinco Puntos Press approached me and said, “If you can write another 50 poems in this kid’s voice, I want to publish that book.”

So I did. At first, however, there were multiple sections, only one of them telling the story of the unnamed protagonist / speaker and his 7th-grade year. Other sections were about celebrations, traditions, music, poetic forms, etc.

It was Bobby Byrd (working as editor of the book) who realized it wanted to be a novel-in-poems. When he pointed this out to me, I pouted for a bit, and then re-read it all. He was right. There was a story that wanted telling.

Once we decided that the collection was going to be a short novel instead, Bobby Byrd asked me to restructure the poems, putting everything in chronological order. Then we took stock, pulling out what didn’t fit the sort of loose plot and making note of the gaps in the narrative. At the end of the day, we realized that — in wanting to appeal to boys ages 9 to 13, a group notorious for not liking poetry — we needed narrative poetry, action, overarching plot, etc.

With that in mind, I then set myself to creating more poetical vignettes to fill in the gaps and address those needs. Before long, the book took on the basic shape it has now.

Weird thing is … I’m usually a HUGE plotter. Like five-thousand word outlines and so on. But this project just grew organically. My mental Güero composed the poems he needed and wanted to compose, and in doing so, he traced his journey through this very difficult year of 2018. All Latinx folx who have lived through its ups and downs as well will probably feel themselves reflected in his own struggle and celebration.

What does poetry do that distinguishes it from other forms of writing?

In They Call Me Güero, the teacher Ms. Wong says, “Poetry is the clearest lens for viewing the world.” The relative brevity, density, and musicality of poetic language allows a writer to express complex ideas in memorable snippets.

And there are characteristics of poetry that make it perfect for young people. It’s a bridge between music and literature, and the playful way in which it shapes language lets kids see how beautiful, melodic, fun and impactful words can be. It is dense, condensed when compared to prose, occupying less space but saying more. As a result, it lends itself to being re-read again and again (something students should learn to do) and rewards close analysis. It can be read out loud, chorally, helping struggling readers and ELLs without shaming them.

In my own life, poetry really impacted me when I was a kid. As an 8th grader, I had a teacher named Bill Hetrick who pulled the lid off of poetry for me, revealing how incredibly powerful it was as a lens for understanding the world and my place in it. Later, when my dad abandoned our family thousands of miles from our hometown, it was poetry that helped me to survive the darkness: reading it, writing it.

Later, as a middle-school teacher, I had a group of boys who just didn’t respond well to the literature we were reading. So I brought in “Oranges” by Gary Soto, a poem in which they could see themselves reflected, adjacent to their own cultural experience as Mexican American kids. It was hugely successful. They identified with the boy in the poem. I was able to get them to try writing about their own lives, to find the “orange” in their own personal stories.

When did you become aware that your red hair and freckles were “different”? How have your ideas about “fitting in” changed over your lifetime?

I always knew I was light-skinned. My family never let me forget it. There’s a paradox to being light-skinned in a culture that is somewhat colorist because of colonialism but that is also marginalized by the larger hegemony of White (non-Latinx) privilege. You simultaneously benefit from being coded or presenting White and get “othered” because of your membership in the marginalized group. Two options seem to present themselves to güeros as a result: betray your culture and adopt the White identity (risking being rejected by ‘true’ White folks) or double-down on your Latinx heritage. Most of us go with the latter, though our complexions are a constant reminder that the structure of the world gives us more power than others in our culture. Finding a way to use that power to advance our common cause is vital in psychological wellbeing of güeros, frankly, and I a lot of my childhood was spent in this internal battle.

You’ve had a long interest in traditional literature, particularly the folklore of Mexico and the border. In fact you’re retold Mexican myths in The Feathered Serpent. Tell us about that.

To clarify, the stories I learned from my grandparents Marie and Manuel Garza (and other uncles, aunts, etc. from the Mexican American side of my family) are border legends that—while certainly rooted in our culture—have only tenuous or obscured connections to pre-Colombian myth. An example would be the Wailing Woman or Llorona, whose parallels in Aztec lore (the vengeful spirit once called zohuaehecatl) are unfamiliar to nearly every Mexican-American in the US. Cultural and religious colonization, shifting national borders, social marginalization: all these factors have worked together to decouple present folklore from indigenous past.

When I got to college (first in my family to do so), I happened to take both an anthropology and a world literature course during the same semester. They exposed me to the literary/scientific value of my family’s legends and their connection to the vast mythology of pre-Colombian Mexico. Though I couldn’t fault any particular individual for the erasure, I was certainly indignant, and decided to “double down” on my Mexican American identity (and, yes, though many of my ancestors are Anglo, I identify Latino). I think this happens to a lot of college-educated Chicanos: feeling our identity has been struck down (to borrow a phrasing from Star Wars), we decide to become more mexicano than anyone could possibly imagine, heh.

In my case, that meant going down the rabbit hole of my cultural heritage, exploring familiar legends in greater (often scholarly) detail (a good chunk of my work comes from this), and then moving beyond the border into Mexico proper, visiting different regions, discovering the particular stories of that area. Then I went even deeper as I saw the glimmer of myth in those folktales, studying the fragmentary record of pre-Colombian belief. I studied Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua people that we now call “Aztecs,” translated their poetry, read their words as recorded after the Conquest.

In my case, I never set out to collect myths. But they gathered in my heart, if I can wax poetic, and I perceived in their frayed edges what felt like the large weft they belonged to. Knowing what they had done for me, how I felt healed after decades of exploration, I wanted to share the tapestry I saw with first other Mexican Americans, taking up the mantle of storyteller and sitting down before my community, convoking them to join with me in this remembering. But I also hope that people just on the edge of that circle of metaphorical firelight will read these tales and better appreciate the often-erased and often terrible beauty of Mesoamerica and her many children in Mexico and the US.

You’ve written with Adam Gidwitz, a fantasy for younger readers that incorporates a lesser-known creature from Mexican lore. Tell us about the book. How does it incorporate your interest in traditional literature?

Once Adam had decided to use his position and power to craft a series of books co-written with writers from marginalized communities, he knew he wanted to do one set on the border (he has a great relationship with students in Laredo), featuring chupacabras as the cryptid (each book has a different creature in need of rescuing). When he approached Matt de la Peña, wondering who might be the best collaborator for that book, Matt immediately said, “Mexican American? Border? Chupacabras? Middle grade? You need to talk to David Bowles.” Or words to that effect, heh.

So Adam reached out to me and I agreed! Working together was really fantastic. We hit it off well, and once I’d outlined the story and we’d revised that outline with the rest of the team, we set about alternating two to three chapters. Writing that way helped us to maintain a rhythm and voice that was true to the other books. But ours was indeed quite different, more politically charged by virtue of its setting. Early on we realized we couldn’t avoid talking about the border wall and misconceptions about border folk, so we took a different tack: we centered that controversy and met it head-on in a compassionate way that kids will be able to understand.

The book itself takes the main characters — Elliot and Uchenna, guided by their teacher Professor Fauna, who established the Unicorn Rescue Society as a young man—to the city of Laredo, where a dead cow leads them to think a chupacabras may be on the prowl. But the city is also in turmoil because of the building of the wall, and the trio find themselves allied with the Cervantes family. Together, they track down a young chupacabras that has been cut off from its pack by the environmentally destructive construction. There’s lots of humor and adventure, but also a serious message about what it takes to bring a community together.

What is diversity in literature and why is it so important?

Ultimately, “diversity” means “verisimilitude.” When books for kids look like the real world around us, with the same breadth and variety of people, then our work will be done. At the moment, however, we are far, far from that goal. Around 3700 books are published each year for kids and teens. Only 800 feature protagonists of color, when in reality 50 percent of school-aged youths are of color. Until that disparity is gone, we will have to fight to see more books published — especially #ownvoices — that center the experiences of children of color.

Everyone has a story to share. What can Americans learn from the voices and stories of immigrants?

Like all voices of specific people from specific places, the stories of immigrants tell us so much about their particular lives and values, their hardships and dreams, their culture and families … And in the discreet details of that apparently very different world, we find the human, the universal, a mirror in which our souls are reflected back, festooned with other colors and clothes, but just as beautiful.

We learn to love our neighbor, and that is how we learn to love ourselves.

What writing advice do you like to give to students, particularly immigrant and bilingual kids?

Write what you know. Write what matters to you. Tell the tales only you can tell, in the words that only you can use. There will be an audience for it, I promise. Somewhere, someone is hungry for your stories. Someone needs them. They will change someone’s life forever.

You have to put what’s in your heart on to that page or that screen. It takes courage, more than you might imagine. But I believe in you. You’re brave enough. Write it down.

___

And this is just what David has done so successfully in his writing. Many thanks to David Bowles for taking the time to thoughtfully answer these questions. I look forward to what’s next from David Bowles!

About the Author

Reading Rockets’ children’s literature expert, Maria Salvadore, brings you into her world as she explores the best ways to use kids’ books both inside — and outside — of the classroom.