A 4th-grade class was learning about Asia as a part of their study of the world. In a story dramatization of the 2500-year-old epic story “The Ramayana,” which is still read and performed as a play all over India and Southeast Asia, the Demon King Ravana was trying to kidnap Princess Sita, wife of Prince Rama. But Carolyn, as Sita, had thrown herself into the role and was successfully resisting Ravana. Jeff, as Ravana, was frustrated but stayed in role and finally improvised a line that kept the story moving forward: “I am the Demon King Ravana and I have ten heads. Can my other nine heads get over here and help me kidnap Sita?” Other students playing demons rushed to his aid, Sita was kidnapped, and the story dramatization continued and played to a successful end.

Learning theory supports the use of drama in the classroom. From his extensive research on child development, Piaget (1962) found that language development goes through three stages: (1) actual experience with an action or object, (2) dramatic reliving of this experience, and (3) words that represent this whole schema verbally. From Vygotsky’s (1986) sociohistorical theory of learning, activity is the major explanatory concept in the development of human thought and language. The use of drama in the classroom, then, reflects a social constructivist perspective of learning that is active, social, centered in students’ experience, and provides an effective way to teach not only the arts, but language, literacy, and other content (Wagner, 2003).

Story dramatizations are based on a story that students are familiar with. While it is planned by students, a script is not necessary. Students know the story and characters well enough to improvise action and dialogue. The dramatization can be recast with different students playing different parts each time it is played so that everyone has an opportunity to step into the roles. Many stories have characters and elements that can be played by several students so that all can participate in a story dramatization.

Research has shown the positive effects of improvised story dramatization on language development and student achievement in oral and written story recall, writing, and reading for both younger students (Pellegrini, 1997) and students through middle school (Deasy, 2002; Fiske, 1999).

Rationale

Strategy

Choose a book to dramatize that is grade-level appropriate and that may be related to other content areas of study in the classroom. Picture books with repeated phrases that students can chant are good choices for younger children. Traditional literature, such as folk tales and myths and legends which may be related to the study of American history, the history and traditions of world cultures, or the ancient world, are good choices for older students. Stories with a clear story line, strong characters, repeated dialogue, and especially a character or element that many students can play at the same time, so that all students can be involved in each playing of a story dramatization, are ideal. Since story dramatizations do not require a written script, students should be very familiar with the story and characters so that they can improvise a character’s actions and speech and so that different students can play different roles each time the story is played.

Read the book aloud to both older and younger students, and older students may read different stories in groups related to a single genre of story (e.g., Greek myths). Lead discussions using reader response questions and prompts, tapping into students’ personal experiences of the story. The teacher and students can then plan and play a story dramatization:

Re-read and discuss the story

So that students are completely familiar with the story, the teacher can do repeated read alouds of picture books for younger students, and older students can read and discuss a story in groups. Ask students to note the setting, characters, and sequence of events or plot, as well as the most exciting parts, the climax, the way the story ended (i.e., the resolution), mood and theme, and important phrases and characteristic things characters say.

Make a story chart

The teacher can record students’ ideas about each of these on chart paper for younger students and to model planning a story dramatization, and older students may do this independently in groups:

Plan for story dramatization

| Setting (Where) | Characters (Who) | Sequence/Plot (When/What) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. | ||

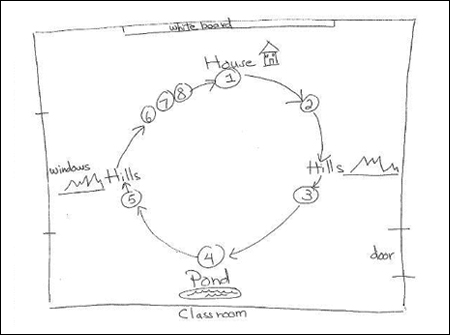

Make a story map

Use the whole classroom space, adjusting furniture as necessary. Make a map of the classroom and place the settings needed for the story. Add the numbered sequence of events of the plot, with arrows showing the direction of the flow of the action.

Take volunteers for the first cast

Do a walkthrough of the story with the first cast. All students can be engaged in each dramatization by using stories that have a type of character that can be played by many students. Or students not playing in the story can be the audience, and then vice versa.

Play the scene

A narrator can be added to read parts of the story. This could be the teacher for younger students, who would also guide students through the actions.

Debrief and discuss

Ask questions that emphasize the positive and make plans for the next playing of the story:

- What did you see that you liked?

- Who did something really interesting (or exciting, realistic, funny, etc.)?

- What can we do next time to make the play even better?

Play the story again

The teacher can take new volunteers to play characters in the story so that all students have the opportunity to step into one of the roles.

Grade-level modifications

K-2nd Grade

Read aloud the classic children’s book by Wanda Gag (2006) Millions of Cats. This is a traditional-type folk tale with two main characters: an old man and an old woman who wish they had a little cat because they are so lonely. The old man goes on a journey to find a cat and instead finds millions of cats. There is a repeated phrase used several times throughout the book, and students can join in with the teacher during the read aloud. Lead a discussion using reader response questions and prompts: What was your favorite part of the story? What did you wonder about? What would you put in a play of the story?

Make a chart to plan the story dramatization and re-read the story as students fill in each of the sections of the story structure as it appears in the story.

A story dramatization plan for Millions of Cats

| Setting | Characters | Sequence/Plot |

|---|---|---|

| Nice clean house with flowers around | Very old man Very old woman | 1. They are lonely. Old woman wants a cat. |

| Over the hill | 2. Old man looks for a cat. | |

| A hill | Millions of cats | 3. He chooses them all. |

| Over the hills | Cats follow him. | |

| A pond | 4. Cats drink water. | |

| Hill with grass | 5. Cats eat grass. | |

| Home to the house | 6. Old woman says too many cats. | |

| | 7. Cats all say I am and fight. Cats ate each other up. | |

| One little cat | 8. One little cat is left. They take care of her and are happy. |

Make a map of the room with students on chart paper and show where each of the setting parts will be in the room by labeling them (see figure above). Students can also draw arrows to show which way the students will move as they play the story and number each of the parts of the steps of the sequence and plot those on the map as well. Simple costume pieces such as a shawl for the old woman, a hat for the old man, headbands with cat ears attached for the cats, or simple paper cat masks can be added.

Ask for volunteers to play the old man, the old woman, and one little cat. The other students can be the millions of cats. The students can take their positions at the beginning of the story. The old man and the old woman are in the house, the cats are on the hills. For younger students, read, or have a student narrator who is already reading, begin to read the book, and pause for the student playing the old man and woman to talk to each other. They can improvise the dialogue. When the old man moves to the hills, the narrator can follow along. All the cats can say the repeated phrase about millions of cats together, follow the old man home, and so on.

After asking students what they liked, adjustments can be made in the story dramatization, new volunteers can be found to play the old man and woman and little cat, and the story can be played again.

There are many excellent picture books with repeated phrases or sounds that all students who are not playing main characters can say so that all students can participate in each story dramatization. The characters or things the students represent, as well as what they can say, are noted in parentheses after the book listing.

Recommended children’s books

- The Three Billy Goats Gruff , by Peter Christen Asbjornsen

- Millions of Cats , by Wanda Gag

- Where the Wild Things Are , by Maurice Sendak

- Caps for Sale , by Esphyr Slobodkina

3rd Grade-5th Grade

Because of the clear and often familiar plot lines and archetypal characters, traditional world tales are excellent choices for story dramatization for students in the middle grades. For example, “The Ramayana” is one of the oldest stories in the world, believed to have been written down by the great Sanskrit poet Valmiki 2,500 years ago. It is famous in India, Indonesia, Thailand, and all over Southeast Asia in books, music, dance, plays, and paintings. There are thousands of versions told in hundreds of languages.

The tale of the Ramayana contains many stories, but the basic plot tells the story of Rama, a Prince of Ayodha, who was exiled for 14 years to the forest with his wife, Sita, and brother, Lakshmana, because of a jealous stepmother. They have many adventures and fight demons. Ravana, a King of the Demons with ten heads, kidnaps Sita, and Rama gets help from the superhero monkey King Hanuman and his army. Hanuman can leap over oceans, carry mountains, and is a symbol of loyalty to Rama. In the end, good triumphs over evil. “The Ramayana” is the basis for the celebration of Divaali, when children perform versions of the stories in India.

Read aloud a picture book version Rama and the Demon King: An Ancient Tale From India (Souhami, 2005) or read aloud chapters from longer versions of the story, for example The Story of Divaali (Verma, 2007) or Ramayana: Divine Loophole, adapted and illustrated by S. Patel (2010), a film animator for Pixar studios. Students could also read the stories independently or in book clubs.

Lead discussions using reader response questions and prompts: What was your favorite part of the Ramayana? Which character did you like the most? Which character would you like to play in a story dramatization?

Plan a dramatization by listing the setting, characters, and sequence of events with numbers in one of the stories in the Ramayana students will play. Students can also draw a large map of the room and show the settings of the story on the map and the numbers of the sequence of events with arrows showing the progression of the action. The main characters are listed here. The setting and plot or sequence of events would depend on which part of the Ramayana students would choose to play.

The Ramayana

| Setting | Characters | Sequence/Plot |

|---|---|---|

| Vishnu, a god and Preserver of the Universe | ||

| King Dashratha, of the great city of Ayodhya | ||

| Rama’s father | ||

| Bharata, Rama’s stepbrother, son of Kaikeyi | ||

| Rama, Prince of Ayodhya, son of king Dashratha | ||

| Lakshmana, Rama’s younger brother | ||

| King Janaka, father of Princess Sita | ||

| Sita, daughter of King Janaka and Rama’s wife | ||

| Hanuman, the Monkey King | ||

| Kaikeyi, Rama’s stepmother | ||

| Ravana, Demon King of Lanka |

Ask for volunteers for the main characters to dramatize the story. Students can improvise the dialogue to tell the story. All students can participate at the same time. Any students not playing one of the characters can form a group that can all be the Demon King Ravana because he has ten heads. Students playing Ravana can link arms and stand in a semicircle to signify that they are all the same character. Ravana can speak from any one of his many heads. Other students not playing main characters can be monkey soldiers in Hanuman’s army.

After playing the story, debrief with students-ask them what they saw that they liked and make adaptations for another playing where students take on parts different from those played the first time. Students can add simple costume pieces such as lengths of cloth over one shoulder, crowns for Rama and Sita, masks for the ten heads of the demon king, or monkey masks for Hanuman and his army.

Students can read the many versions of the Ramayana independently or in book clubs, or the stories can continue to be read aloud.

Recommended children’s books

- The Ramayana for Young Readers , by Milly Acharya

- Tales from India , by J. E. B. Gray

- Hanuman: The Heroic Monkey God , by Erik Jendresen

- Ramayana: Divine Loophole , by Sanjay Patel

- Hanuman , by Radhika Sekar

- The Ramayana for Children , by Bulbul Sharma

- Rama and the Demon King , by Jessica Souhami

- Hanuman’s Journey to the Medicine Mountain , by Vatsala Sperling

- Ram the dDemon Slayer , by Vatsala Sperling

- The story of Divaali , by Jatinder Verma

- Rama and Sita: A Tale From Ancient Java , by David Weitzman

- Where’s Hanuman? , by Christopher Woods

Differentiated Instruction

English language learners

Several English language development strategies are used in story dramatization. Visuals such as book illustrations and charts for planning and mapping a story dramatization are used. English learners can participate in a drama using nonverbal means such as facial expression, gestures, and movement to communicate meaning and demonstrate understanding. The collaborative nature of drama provides student to student interaction in a meaningful context. Stories from the cultural heritage of the English learners in the class can also be chosen. For example, the example in the 3-5 section uses the Ramayana, an epic tale known, read, and performed in India and all over Southeast Asia. English learners of Indian or Southeast Asian heritage, such as Thai, Vietnamese, or Indonesian students, can benefit from prior knowledge they may have of this story and the characters. The students’ heritages are also being acknowledged in class.

Recommended children’s books

- Stories From around the World , by Heather Amery

Struggling students

Struggling students can fully participate in story dramatizations. Listening to the stories read aloud and viewing charts and maps for planning a dramatization can scaffold learning. Students can also pair up with a drama buddy in parts that can be played by more than one student for peer support.

Assessment

A self-assessment that requires students to reflect on the story and their role m dramatizing it can be used with questions and prompts such as the following:

- Tell about the story.

- Tell about the character or characters you played in the story.

- What was the most important thing about the story?

- What was the most important thing about your character or characters?

- What did you like best about dramatizing the story?

Resources

Heinig, R. B. (1992). Improvisation with favorite tales: Integrating drama into the reading/writing classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cox, C. (2012). Literature Based Teaching in the Content Areas. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.