Focused read-alouds can be a valuable method for scaffolding genre knowledge.

“I think I’m going to make a table of contents in my information book, because some of the real ones we read had a table of contents on the back cover,” Dana (all student, teacher, and school names are pseudonyms) declared as she finished the title page of her information book following our focused read-alouds of information books about weather. Leon thought for a minute and then nodded in agreement, “I’m making a table of contents at the beginning, but I’m going to wait on the index until I see how much I fill up in my book.” Similar to what Lancia (1997) and Kamberelis (1998) have found, these students are making decisions as authors that reflect their literacy diets and reading experiences. Their teacher, Mrs. Strickland, a 25-year veteran with national board certification, explained,

My second graders love information books, because they are interested in the topics and like to read facts. I regularly introduce a range of informational books during science units. We explore books, write book reports, and construct projects, but my students have never had the chance to create their very own information books from scratch.

Such conversations between Linda (first author) and Mrs. Strickland began when Linda was supervising preservice teachers at Winterville Elementary School, which serves lower to middle class students with diverse backgrounds and has experienced teachers who are enthusiastic about working with the local university. Linda was working with Carol on a research study of children’s writing development in different genres (Donovan, Golson, & Smolkin, 2003; Donovan & Smolkin, 2005, in press) and enjoyed talking with Mrs. Strickland about her students’ writing. These conversations led to an examination of the information book compositions of 13 of her students within a science unit focusing on the writing of informational texts.

Like Mrs. Strickland, we know that skill with informational text is crucial to success in today’s information- driven world (Kletzien & Dreher, 2004; Saul & Dieckman, 2005; Young & Moss, 2006) and that to become effective communicators, children must learn to read and write information for multiple audiences and in various forms (Kamberelis, 1999; Tower, 2005). So, we were thrilled when she expressed interest in incorporating informational writing in an upcoming unit that led to the instruction and student writing we present in this article. We provide a clear example of focused instruction designed to support primary-grade students’ reading and writing of informational texts.

We begin with a brief overview of the information book genre, followed by examples of students’ information book compositions. Although Mrs. Strickland’s class had previously written responses to information texts in science and simple one-page informational reports of facts, these students had not had the opportunity to write more extended informational texts on their own. They also had no previous instruction addressing how authors organize or use language in specific ways in information books. We know that primary- grade teachers are becoming aware of the importance of using information books in their classrooms, and our understanding of the potential of information books for young readers and writers is growing tremendously. Some researchers are studying the impact of information book use in science (e.g., Pappas & Varelas, 2009), but we have little information about how a systematic approach to helping students identify information books’ elements and features will help improve their understandings of how to read and write informational texts.

Information books in classrooms

Over the past 10 years, interest in information book use across elementary-grade levels has grown. University and teacher researchers have examined information book use and informational writing in elementary schools with increased frequency (e.g., Donovan, 2001; Dorfman & Cappelli, 2009; Dreher, 2003; Moss, 2004; Read, 2005; Saul & Dieckman, 2005). Children enjoy information books on science topics, will self-select them when given the opportunity, and have specific reasons for their selections (Donovan & Smolkin, 2006). Read-alouds of information books have been found to provide an engaging means of discussing genre features and content with primary-grade students (Oyler & Barry, 1996; Pappas & Varelas, 2004; Smolkin & Donovan, 2001), and experience with them has been shown to support genre knowledge (Kamberelis, 1998; Kamberelis & Bovino, 1999; Pappas, 1991, 1993) as well as content knowledge (Pappas & Varelas, 2009).

We know that elementary students have knowledge of the information book genre typical of informational picture books (e.g., Donovan & Smolkin, 2002a; Duke & Kays, 1998). Furthermore, examinations of students’ writing have shown that they possess and use knowledge of information book genre elements in their writing from a young age (Chapman, 19 95; Donovan & Smolkin, 2002b; Duthie, 1994). Many have begun to suggest ways to support children’s informational text writing that may result in more sophisticated written products (Duke & Bennett-Armistead, 2003; Lewis, Wray, & Rospigliosi, 1994; Stead, 2001). The work of those examining the reading-writing connection (Kletzien & Dreher, 2004; Ray, 1999; Stead, 2001) and use of mentor texts (e.g., Dorfman & Cappelli, 2007, 2009) suggest that the read-aloud with explicit teaching of genre elements is a promising instructional enhancement (Lancia, 1997).

Information books are those with the major purpose of reporting facts about the general nature of a thing or an animal, such as Weather Words and What They Mean by Gail Gibbons. These types of books include certain elements and features. Pappas (2006) has identified four obligatory elements of information books (i.e., topic presentation, descriptive attributes, characteristic events, final summary) and eight optional elements (i.e., prelude, category comparison, historical vignette, experimental idea, afterword, addendum, recapitulation, illustration extension). The additional aspects of information books that we refer to as features include table of contents, headings, index, pictures and photographs, diagrams, captions, technical vocabulary, generic nouns, and timeless present tense.

Understanding these genre-specific elements and features, how informational texts are organized (Donovan & Smolkin, 2002a), and students’ understandings about these features will allow teachers to construct appropriate contexts and instruction to further develop students’ genre knowledge. So, we asked Mrs. Strickland’s second graders to write their first information book compositions to determine what they already knew about the genre and what they might learn from explicit attention to genre elements and features during information book read-alouds.

Assessing students’ first information books

Blank books were used to encourage students to demonstrate their knowledge about a topic of interest and a typical information book’s format, elements, and features. Because our focus was on the use of genre knowledge, we asked students to write on familiar topics. We wanted to see their growth in use of genre knowledge following the fairly easy addition of focused information book read-alouds to a science unit. We were looking specifically for how students would incorporate typical information book elements, including a topic presentation, descriptive attributes, characteristic events, comparisons, and a final summary. See Table 1 for examples of each element in a read-aloud text and student composition.

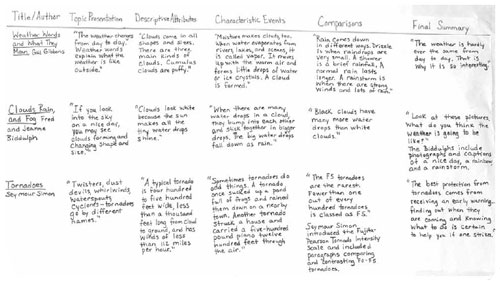

Table 1: Information book elements in a sample text and second-grade authors’ compositions

| Information book genre element and function | Examples from Weather Words and What They Mean | Examples from second grade authors |

|---|---|---|

| Topic presentation provides the introduction of the topic. | “The weather changes from day to day. Weather words explain what the weather is like outside.” (n.p.) | “Frogs are interesting creatures.” (Natalie) |

| Descriptive attributes describe characteristics of the topic. | “Clouds come in all shapes and sizes. There are three main kinds of clouds. Cumulus clouds are puffy.” (n.p.) | “Earth is the planet we live on. It is 75% water and 25% land.” (Antoine) |

| Characteristic events describe typical actions, processes, or events engaged in by the topic (what the topic does). | “Moisture makes clouds, too. When water evaporates from rivers, lakes and oceans, it is called vapor. It moves up with the warm air and forms little drops of water or ice crystals. A cloud is formed.” (n.p.) | “Monkeys climb on trees.” (Cionna) |

| Comparisons compare and contrast different types of the topic. | “Rain comes down in different ways. Drizzle is when raindrops are very small. A shower is a brief rainfall. A normal rain lasts longer. A rainstorm is when there are strong winds and lots of rain.” (n.p.) | “And like a lion, it [a cheetah] is also a cat.” (Kim) |

| Final summary summarizes information presented in the book related to the topic. | “The weather is hardly ever the same from day to day. That’s why it is so interesting.” (n.p.) | “There are so many animals, I hope you like the ones I talked about.” (Hannah) |

Adapted from “The Information Book Genre: Its Role in Integrated Science Literacy Research and Practice,” by C.C. Pappas, 2006, in Reading Research Quarterly, 41(2), 226-250. From Weather Words and What They Mean, by G. Gibbons, 1990, New York: Holiday House. Reprinted with permission.

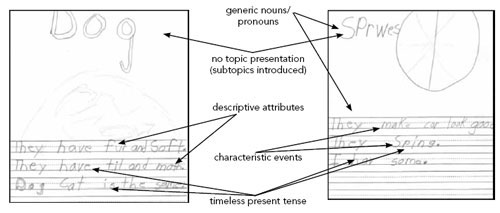

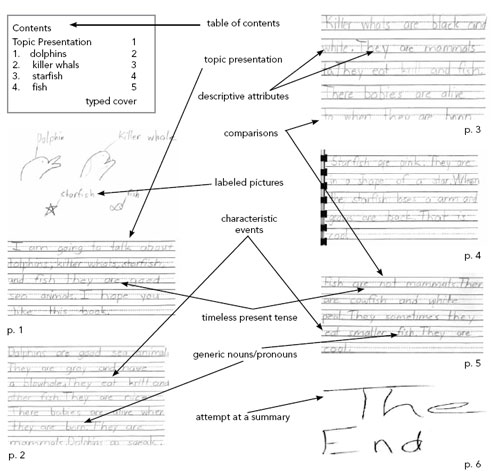

In addition, we wanted to see how students would include typical features of information books (i.e., table of contents, headings, index, pictures and photographs, diagrams, captions, technical vocabulary, generic nouns, timeless present tense). The language we used to code elements and features in student compositions matched the language we used with students during instruction (see Table 1). Our figure arrows in student compositions point to specific words, clauses, or illustrations that provide examples of how students used information book elements and features. For example, in Figure 1, arrows point from the “generic nouns/pronouns” label to “sprwes” [spinner wheels] and “they” in the student’s text.

Figure 1: Isaiah’s first informational composition in second grade

These are two representative pages of Isaiah’s six-page composition. He also included a cover and other pages with facts on unrelated topics.

In these first compositions, students demonstrated awareness of elements and features that differentiate information books from other school genres. No student wrote a fictional story or personal recount, and all students included facts about the topic and subtopics they chose. Most students used some generic nouns (e.g., “Comets are space rocks.” by Antoine), timeless present tense (e.g., “Dogs have sharp teeth. They can bite you.” by Fred), and technical vocabulary (e.g., “They [dolphins] have a blowhole to breathe with. They are a mammal.” by Dana) in their first compositions. This supports earlier work showing that by second grade, students have a sense of the different language structures appropriate for different purposes (Donovan, 2001; Kamberelis, 1999).

The students’ compositions varied greatly, though, in their inclusion of elements and the ways they selected and organized information. Two pages of Isaiah’s first composition are shown in Figure 1. He has written on five different topics, one for each page of the text. He includes three typical information book elements: descriptive attributes (“They have fur and soft.”), characteristic events (“They make car look good.”), and a simple comparison (“Dog cat is the same.”). Isaiah has headings on each page and includes a labeled picture for “sprwes” [spinner wheels]. He mixes the stance between third person (“They spins.”) and first person (“I have some.”). Thus, he demonstrates knowledge that information books provide facts on topics, usually in third person. Isaiah’s book is similar to four others, in which students produced compositions on several different topics.

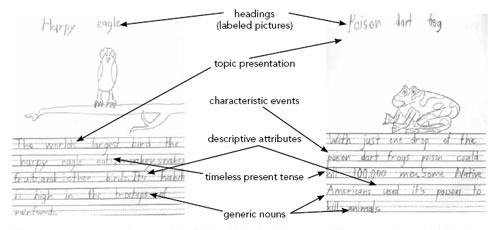

In comparison, Michael’s first composition (see Figure 2) demonstrates more sophisticated use of language, elements, and features. He identifies his overarching topic, animals, and then introduces a new animal on each page. His clauses that represent typical information book elements, specifically descriptive attributes (“Some Native Americans used it’s poison to kill animals.”) and characteristic events (“With just one drop of the poison dart frog’s poison could kill 100,000 men.”), are more complex. Three labeled pictures serve as headings for his entire composition, and he uses third person throughout. Michael’s book is similar to the first books of six other students, who demonstrated that typical information books focus on a single general topic with specific, detailed subtopics.

Figure 2: Michael’s first informational composition in second grade

These are two representative pages from Michael’s book of four pages. The arrows point to the following representative examples of elements and features: topic presentation: “The world’s largest bird [is] the harpy eagle”; characteristic event: “…the poison dart frog’s poison could kill 100,000 men”; descriptive attributes: “It’s habitat is high in the treetops of rainforests”; timeless present tense: “eats,” “is,” “could kill”; generic nouns: “treetops,” “Native Americans,” “animals.”

This initial assessment of students’ information book writing provided Linda and Mrs. Strickland an opportunity to consider the continuum of compositions in terms of genre element use, feature use, and organization. Most students used generic nouns, timeless present tense, and pictures in these first compositions. Many included descriptive attributes and characteristic events. Like Isaiah, some students’ initial sense of information book organization seems to have been a collection of facts, which is a consistent organizational pattern for students’ informational writing (Donovan, 2001; Newkirk, 1987), but others like Michael demonstrated more sophisticated organization. Six of the students’ compositions did not include headings, while seven incorporated headings within illustrations. Approximately half of the students included the optional element comparisons in some way; however, very few students included topic presentations or final summaries, which is reasonable based on the students’ lack of prior experience composing an entire information book.

Therefore, along with Mrs. Strickland, we explored possibilities for increasing the students’ competence with informational writing. Given that the work of those examining the reading-writing connection (e.g., Kletzien & Dreher, 2004; Ray, 1999) and use of mentor texts (e.g., Dorfman & Cappelli, 2007, 2009) have suggested the read-aloud with explicit teaching of the genre elements as a promising instructional tool, we believed that this minimal instructional enhancement might provide insights into what genre elements, features, and organizational patterns are easily taken up by students. Mrs. Strickland was enthusiastic to examine the students’ writing for evidence of growth in their content and genre knowledge.

Teaching about the information book genre

Linda served as a visiting science and writing teacher for three weeks with Mrs. Strickland’s class during a unit on weather. In addition to providing content about weather, we designed this instructional unit to build knowledge of information book organization, genre elements, and text features. We selected typical information books (Pappas, 2006) based on students’ interests in weather. We made notes about genre-specific elements and features to introduce to students as well as interesting ways authors decided to organize information. These objectives were woven together during nine 45-minute instructional sessions (see chart below) that included focused readalouds of five information books, discussions to introduce and provide students with language for how information books work, and class activities in which students could explore the information book genre.

Description of a second-grade instructional unit on weather

Session 1: Read aloud Weather Words and What They Mean by Gail Gibbons

- Introduce reading like writers.

- Explore genre features (e.g., speech bubbles, technical vocabulary, clear organizational structure).

Session 2: Revisit Weather Words and What They Mean for genre element identification

- Introduce information book elements: topic presentation, descriptive attributes, characteristic events, comparisons, and final summary.

- Review use of speech bubbles, illustrations, and technical vocabulary.

Session 3: Read aloud Clouds, Rain, and Fog by Fred Biddulph and Jeanne Biddulph

- Compare with Weather Words and What They Mean.

- Explore text features (e.g., table of contents, headings, pictures, diagrams, and captions).

- Identify elements from each text.

Session 4: Read aloud Tornadoes by Seymour Simon

- Examine technical vocabulary from each book.

- Discuss the research that information book writers must do.

- Explore specific text features (e.g., captions, diagrams).

- Identify elements.

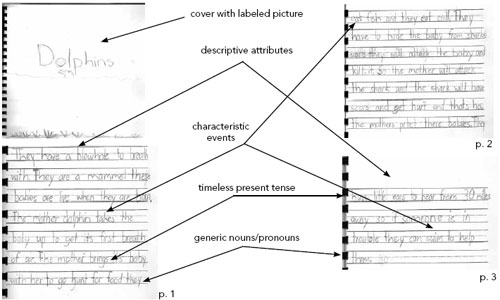

Session 5: Introduce the genre element comparison chart

- Create a comparison chart of elements included in the three books previously discussed.

Session 6: Read aloud Super Storms by Seymour Simon

- Identify elements.

- Begin planning for students’ information books.

Session 7: Read aloud Lightning by Seymour Simon

- Identify elements and features.

- Through shared writing, identify and compare elements and features in the five informational books previously discussed.

Session 8: Have a genre scavenger hunt

- Identify elements and features.

- Explore a variety of information books.

Session 9: Read aloud Wind and Storms by Fred Biddulph and Jeanne Biddulph

- Review the K-W-L chart strategy and complete the “L” column on what the students have learned in the unit.

- Discuss genre features and elements.

- Plan for students’ information book compositions.

Building knowledge regarding how authors make decisions about organization began during the first session. Linda suggested that students “read and think like a writer.” Similar to the way Beck and McKeown (2002) discuss questioning the author, Linda asked students to consider authors’ decisions:

I want you to think like a writer for a minute. What did Gail Gibbons do to organize her thoughts?”

As the class read additional books, they compared and contrasted the authors’ decisions. During the reading of Clouds, Rain, and Fog by Fred Biddulph and Jeanne Biddulph (1993), Linda noted,

As we read, I want you to think like a writer about how these authors made decisions for the book. I notice something that is different from the very beginning of this book.”

For example, students quickly identified the following differences between the first and second information book read-alouds:

Dana: There’s a table of contents.

Linda: Yes, I didn’t see that in the Gail Gibbons book.

Eddie: It looks real.

Linda: I think that’s a really good observation. It is different from Gail Gibbons’s book. This book has photographs.

Brad: It has real pictures.

Hannah: It has clouds in the other book, and the other book has a sun and two and three [words] and stuff like that.

Fred: The words ain’t written in bubbles …

Linda: I am noticing a pattern that these authors use on every page. What do these authors do to tell us they are about to start a new topic?

Leon: A question.

Linda: Yes, they use a question as a heading to let us know each topic is beginning. Then, they answer their question in a paragraph.

In connection with our content focus on weather, we chose to emphasize the information book elements topic presentation, descriptive attributes, characteristic events, final summary, and comparisons (Pappas, 2006). Linda introduced each information book element during the second instructional session, and she and the class created an elements chart (i.e., a large chart listing an example of each genre element as found in the book). The following transcription shows how the genre element comparisons was discussed during this exercise:

Linda: What is this word?

Eddie: Comparison.

Linda: Yes, comparison. Now listen to this page to see if you can point out the comparison. “Clouds come in all shapes and sizes. There are three main kinds of clouds. Cumulus clouds are puffy. They are fair weather clouds. Cirrus clouds are the highest clouds. They mean fair weather, too. Stratus clouds are low, gray clouds. Sometimes, they bring rain or snow” [Gibbons, 1990, n.p.; reprinted with permission]. What was Gail Gibbons comparing?

Juanita: The clouds.

Linda: Right, Gail Gibbons compared different types of clouds. This elements chart helps us to learn about how information books work. Authors introduce the topic, describe the topic, and tell us what the topic does. Sometimes they compare things about the topic. Then, they give us a final summary.

Linda named every element, and the class found and discussed an example from the book to reinforce the specific ways that information books convey information. A similar activity in session 5 used a comparison chart to look at examples of each element in the three books the class had read to that point (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison chart of information book genre elements

As focused read-alouds continued, students had opportunities to identify where authors incorporated information book elements. The following exchange occurred as students discussed Seymour Simon’s (1997) Lightning during session 6:

Linda: What is one thing that Seymour Simon described?

Brad: He described lightning and how hot it is.

Gene: I was going to say the size of hail.

Linda: Right, what is another thing he described?

Cionna: Rain.

Kim: Wind.

Linda: What are some characteristic events where he told us what a storm does?

Michael: Lightning can make a fire.

Fred: Fire or bad stuff.

Linda: Yes, a storm can do damage.

Leon: He told us that hurricanes wash away beaches.

Isaiah: It [a storm] can snap trees in two.

Given this new language for identifying elements of information books, Linda guided discussions to help students build knowledge of weather and genre elements that might be applied in their own writing.

Linda also introduced and asked students to notice the following text features throughout the instructional unit: tables of contents, headings, indexes, pictures and photographs, diagrams, captions, technical vocabulary, generic nouns, and timeless present tense. As we learned from their first compositions, the students already had some prior knowledge of these elements, so focused read-alouds were used to draw students’ attention to features and to give them language for discussing each.

For example, during the reading of Tornadoes, Linda highlighted his use of specialized weather vocabulary, such as downdraft, funnel, and meteorologist. She supported students as they began to notice captions, features like tables of contents and indexes that help organize information books, and differences between illustrations and photographs. One student shared the following insight during the reading of Clouds, Rain, and Fog:

Linda: They use captions on this page to tell us exactly what kind of weather each picture shows. A lot of information books will use captions. What else do you notice?

Leon: An index that helps us know where stuff is and where to look, it tells us where to find something you want to look at.

Linda also led students in a text feature scavenger hunt. This activity provided students an opportunity to apply understandings about information book features in a scaffolded setting. Students drew a sticky note from a bag with the name of a feature, located the feature in a book, and placed the sticky in the book to share with others. Later, students had opportunities to identify information book elements and features in new texts while working at their tables.

Assessing students' second information books

The short unit seems to have supported student gains in all objectives: organization, genre elements, and genre features. Not all students composed second books that differed dramatically from their first in terms of the types of information book elements included, but all provided evidence of new knowledge of information book elements, features, and organization.

Students’ attention to elements, features, and craft

Students included more clauses categorized as typical information book elements from their first books to their second. Yet, descriptive attributes and characteristic events were the elements that represented the greatest increase across samples. Students included more consistent use of generic nouns and timeless present verbs in their second books. Also, the number of labeled pictures doubled following instruction. Several students added tables of contents, with two students incorporating the language of elements by listing “Topic Presentation” in the contents. This particularly interesting insight demonstrates how students learned about an important element in information books and named it for their readers.

While their second information books demonstrated increasing facility with elements and features, the students continued to reflect the voices and interests of second-grade writers. Dana’s and Leon’s compositions provide examples of the complexity that Kamberelis (1998) described regarding the ways that students learn and apply genre knowledge. Dana’s first book (Figure 4) demonstrates a great deal of knowledge about dolphins and includes descriptive attributes and characteristic events about one animal and several information book features. However, her second composition (Figure 5) shows how she systematically attempted to organize more elements and features when writing on a similar topic.

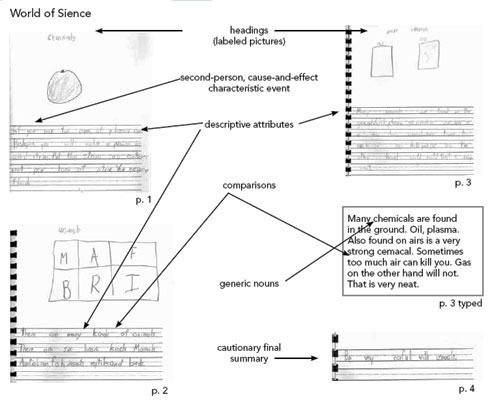

Figure 4: Dana’s first informational composition in second grade

Figure 5: Dana’s second informational composition in second grade

While Dana’s use of elements and features increased and her organization improved, her second composition still included statements like “They are cool” and “I hope you like this book,” which differ from the information books we read together. As the opening conversation suggests, Dana had learned from the weather books in the unit that information books often contain a table of contents and index, two important features she had not included in her first book. Her page numbers for each subtopic matched her table of contents. Interestingly, Dana and one other student wrote “Topic Presentation” as the first item in their table of contents, a clear example of how students inserted language about information book elements. In addition to her topic presentation, she included descriptive attributes, characteristic events, and simple comparisons. Her second book also includes one labeled picture on the first page. Each subsequent page focuses on a different sea animal.

Leon’s compositions both reflect strong content knowledge. His first book (Figure 6), titled “World of Sience” [sic], describes chemicals and animals. He wrote mostly descriptive attributes with a characteristic event related to cause and effect. He used technical vocabulary in this four-page composition, which primarily describes two subtopics within science. He also included a final summary.

Figure 6: Leon’s First informational composition in second grade

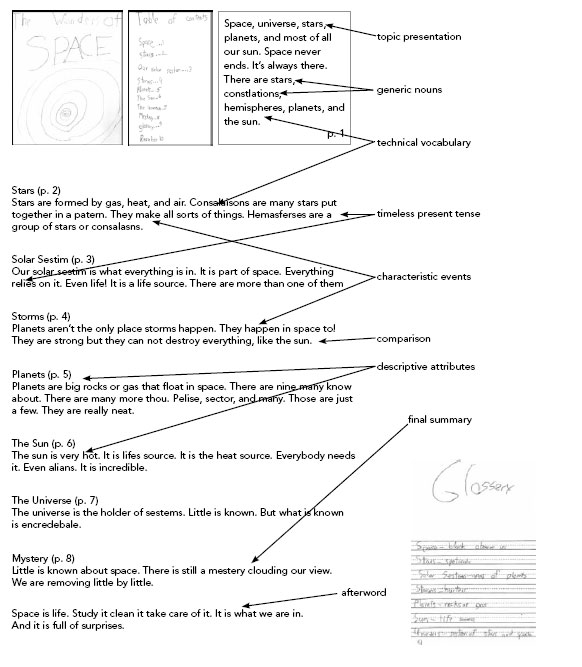

Following instruction, Leon’s second composition is an example of one with very sophisticated use of elements and features (see Figure 7). He asked to add additional pages to this book, and he also included a table of contents, which he discussed with Dana. On each page, he introduced a new subtopic related to space with a labeled picture. Leon’s 10-page composition is a good example of a text that includes all information book elements: topic presentation, descriptive attributes, a characteristic event, comparisons, and a final summary. He also added an afterword, an optional information book element, similar to the one in Tornadoes. Leon’s glossary, similar to the one from Clouds, Rain, and Fog, appeared near the end of his composition. Most of the text is written in third person; however, he uses second person in his afterword, which is similar to those in the information books used during instructional sessions.

Figure 7: Leon’s second informational composition in second grade

The central change for Leon following instruction was his ability to focus the book and organize elements and features in ways that connected the information he chose to express as an author. Organization of information was a noticeable shift that occurred for many students following the unit.

Students’ attention to organization

Students organized their second books more like the ones read during instruction. Following instruction, seven students wrote information books on a single topic, four wrote on a central topic with subtopics, and two wrote on related subtopics with an inferred general topic. This differed from the first books, in which four students wrote about unrelated topics on each page. For example, in his first book, Fred wrote the following, with each subtopic on a new page:

Dogs

Dogs have sharp teeth. They can bit [bite] you. Some are mean. Some are nice. They could be both. But I like them. My favoit [favorite] one is a pick [pit] bull. It could fight bad. It bites other people.

Rims inversion [conversion]

Rims are silver. Some are gold. But I like silver. They make your car tight. Some never stop when you stop at a red light. Those are called rims never stop.

X-Box

X-Box are fun. They got tight games like NBA Drive 2003. It got Master P songs. They can shout good, really good. 76ers are my favoit [favorite] team.

Horse

Horses are fun. You get to ride them. They got long hair. They live in a farm or a field. They are fun running.

#1 [Nike Air Force 1 sneakers]

They are green and white, but I like the GO Air Force 6. They are tight to me and my friends.

In his second two-page composition, Fred wrote,

Basketball

The rule is to not try to foul people. You have to dribble the ball. You dunk. You can shoot a 3. Iverson play 76ers is a good player. Kobe for the Lakers is too. Jordan is too for the Wizards. McGrady is too for Magics. Cater is too for Rapters. [page break]

Every player must play. Cause some get tired. So that’s why you should let everybody play. Some are not good. Some are good. But my favorite player is Allen Iverson. The end.

Fred’s second book still incorporates loosely connected facts on each page, but the two pages are related to the topic, basketball, whereas subtopics in his first piece were unrelated.

This greater attention to organization occurred for all 13 students. Class discussions during the readalouds about how authors organize their books, stay on topic, and choose subtopics may have contributed to this change:

Linda: I want us to keep thinking about how authors make decisions about their books.

Gene: They organize their ideas.

Linda: Authors organize into topics and subtopics.

Kim: They tell what our topic does.

These focused conversations, as well as the books read aloud and discussed, seem to have impacted the students’ abilities to organize their second information books more effectively.

Final thoughts

Students’ use of genre elements was greater and their writing more focused following the simple inclusion of information book read-alouds that included discussion of genre elements, features, and organization. Students’ first compositions indicated knowledge of the information book genre. However, they seemed to know less about how to organize the information by using the structure of typical elements and features.

For example, Leon, Michael and Dana all wrote first information books that were interesting and included technical vocabulary, genre elements, and illustrations, but after the instructional unit on weather, the compositions of these students looked and read more like “real” information books.

Like Read (2005), we found that students were able to generalize genre knowledge to their own topics. Thus, this project supports the use of model texts as important scaffolds for writing instruction (Donovan et al., 2003; Dorfman & Cappelli, 2009; Hillocks, 1986; Kamberelis, 1998; Lancia, 1997) and the repeated exploration of model texts to discuss the elements and features of typical information books. We believe Kamberelis’s (1998) notions, that children’s literacy diets impact their writing and that genre knowledge develops in complex ways, are exemplified in this examination of instruction and information book writing.

In this short unit, many of the students demonstrated more sophisticated organization of genre elements and features of the information book genre as well as efforts to craft more realistic information books. Students’ books reflected our class discussions regarding authors’ decision-making processes. These changes suggest that the simple curriculum addition of focused read-alouds may be a valuable method for scaffolding genre knowledge.

A teacher knowledgeable of genre elements, features, and organizational patterns will be able to routinely direct young students’ attention to them during read-alouds within meaningful contexts, to assess student compositions for the ways in which the students apply these insights, and to invite students to examine their own texts for elements, features, and organization as well.

This link between instruction and assessment has potential to improve instruction and writing, thus broadening and supporting young students’ informational genre knowledge in important ways, especially given the challenge that many students and teachers face when seeking to organize content knowledge within informational writing.

Bradley, L. G. and Donovan, C. A. (2010), Information Book Read-Alouds as Models for Second-Grade Authors. The Reading Teacher, 64: 246–260. doi: 10.1598/RT.64.4.3