Introduction

Children’s literature plays an essential role in the literacy development of children. This article focuses on the teaching and use of children’s literature and provides educators with information about a wide range of books across multiple genres that are representative of the diverse world in which we live.

A strong emphasis is placed on the importance of having diverse library collections that take into account numerous factors, such as race, class, disability, and religion. This article also offers innovative approaches for bringing children and books together, as well as content analyses and rich descriptions of titles that share common features (e.g., endpapers, the blending of poetry and nonfiction).

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.” (Rudine Sims Bishop, 1990, p. ix)

Bishop’s analogy of mirrors and windows is an important one for educators to think about, no matter the demographics of the schools in which we teach. Books have the potential to entertain, foster a love of reading, and inform while also affirming the multiple aspects of students’ identities and exposing them to the values, viewpoints, and historical legacies of others. The mission of the We Need Diverse Books grassroots movement, which began in 2014, is to put “more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children.”

Although this movement may have recently led to a renewed focus on the importance of diverse books, it should be noted that this issue has been an important one for many years, especially for librarians and educators of color such as Charlemae Rollins, Pura Belpré, Effie Lee Newsome, and Rudine Sims Bishop. They all recognize the importance of children being exposed to diverse reading material.

In this column, I provide suggestions for educators on how to develop diverse classroom libraries. These ideas and suggestions are also applicable for school and public librarians. I focus on diversity using a two-pronged approach, the first of which is cultural diversity with attention to factors such as race, class, and disability. The second focus is diversity in regards to genres and subgenres.

Cultural diversity

The main types of cultural diversity that I reference are race, class, and disability. Other important cultural markers, such as language, sexual orientation, and religion, are equally important; books related to these additional markers are included in a recommended sample listing (see Table 1).

Table 1. A Sampling of Recommended Diverse Literature, Alphabetized by Author

The books listed here include recently published titles as well as older titles and a few classics — with an emphasis on culturally diverse literature — that I believe belong in K–6 classroom libraries. There are other titles (e.g., Pink Is for Blobfish) included that are not necessarily culturally diverse but that I believe children will enjoy reading. In short, this sampling of books is a microcosm of what I would consider to be an exemplary classroom library that is inclusive in regards to cultural identity markers (e.g., race, class, gender), as well as genres and subgenres.

|

|

Racial diversity

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison collects statistics about the number of books published annually that are written by and about people of color. Although the numbers are bleak, when one goes back several years looking for notable books written by and about people of color, there are enough available and in print for teachers to have an adequate supply of books in their libraries. This is not to say that there is not a need for more children’s books written by and about people of color; rather, there are books available for now to begin sharing and using with students.

One way for teachers to be aware of notable books written by and about people of color is to become familiar with race-based awards such as the Coretta Scott King Book Award , the Pura Belpré Award , the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature , and the American Indian Youth Literature Award .

It should be noted that these race-based awards were created because, for many years, authors and illustrators of color have not received the most prestigious awards, such as the Newbery and Caldecott medals and honors awarded by the American Library Association (ALA). For example, the Newbery Medal has been given annually since 1922, but as of the 2016 awards, only four books by African Americans had received it: M.C. Higgins, the Great by Virginia Hamilton, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor, The Watsons Go to Birmingham — 1963 by Christopher Paul Curtis, and The Crossover by Kwame Alexander.

Giving race-based awards brings attention to some titles that might not receive as much attention otherwise. For example, in 2015 and 2016, there were several outstanding books that received a race-based award, including Gone Crazy in Alabama by Rita Williams-Garcia (see Figure 1), I Lived on Butterfly Hill by Marjorie Agosín, Blackbird Fly by Erin Entrada Kelly (see Figure 2), and In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse by Joseph Marshall III (see Figure 3). Were it not for race-based awards, these titles would not have received major prizes.

Figure 1: Cover of Gone Crazy in Alabama by Rita Williams-Garcia

Note: From Gone Crazy in Alabama, by R. Williams-Garcia, 2015, New York, NY: Amistad. Copyright 2015 by HarperCollins. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 2: Cover of Blackbird Fly by Erin Entrada Kelly

Note: From Blackbird Fly, by E.E. Kelly, 2015, New York, NY: Greenwillow. Copyright 2015 by HarperCollins. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 3: Cover of In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse by Joseph Marshall III

Note: From In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, by J. Marshall III,2015, New York, NY: Abrams. Copyright 2015 by Abrams. Reprinted with permission.

The Coretta Scott King Book Award is given to African Americans who write exceptional books about the black experience. The award, which has been in existence since 1970, has created a canon of high-quality books for teachers to choose from.

The Pura Belpré Award , named after the first Latina librarian in the New York Public Library, is given to “a Latino/Latina writer and illustrator whose work best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience in an outstanding work of literature for children and youth” (Association for Library Service to Children).

The American Indian Youth Literature Award honors exceptional writing by and about American Indians, and the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature honors books about Asian/Pacific Americans.

In addition to shining a light on particular award-winning titles each year, the awards introduce authors and illustrators to the children’s book world. Although authors and illustrators are unlikely to win an award each year, learning about them when they do win can lead educators to seek out other titles that the winning authors and illustrators may produce over the course of their careers.

Class

Aunt Flossie’s Hats (and Crab Cakes Later) and other family stories by Elizabeth Fitzgerald Howard feature middle and upper class African Americans who were teachers and medical doctors in the early 1900s. The depiction of African Americans as professionals is important for children to see and recognize that African Americans can be members of various socioeconomic groups.

However, not all children are middle or upper class, and they too should see their experiences reflected in books. Although there are certainly challenges directly related to poverty, there are books that show poor people in positive and realistic ways as caring about the communities in which they live and members of those communities.

One example of such a book is Something Beautiful by Sharon Dennis Wyeth (see Figure 4), about a girl who lives in a neighborhood that has many low-income families. After learning about the word beautiful in class, she goes in search of “something beautiful” in her community. At first, she only sees a homeless woman and some graffiti, but with the help of people who live in her community, she soon sees that there is beauty there, too, and that she is also able to make it more beautiful by removing the graffiti, for instance.

DeShawn Days by Tony Medina is a collection of poems about a boy who lives in the projects, and then there is My Very Own Room/Mi Propio Cuartito by Amada Irma Perez, about a girl who lives with a large family in a small, crowded house and dreams of having her own quiet space. Barbara O’Connor has written a number of notable middle-grade novels (e.g., How to Steal a Dog, The Fantastic Secret of Owen Jester; see Figure 5) with characters who are a part of poor or working-class families.

Reading widely and paying attention to issues of class as they appear in books is one way for teachers to select and include in their classroom libraries children’s books that depict a range of socioeconomic groups.

Figure 4: Cover of Something Beautiful by Sharon Dennis Wyeth

Note: From Something Beautiful, by S.D. Wyeth, 1998, New York, NY: Dragonfly. Copyright 1998 by Random House. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 5: Cover of The Fantastic Secret of Owen Jester by Barbara O’Connor

Note: From The Fantastic Secret of Owen Jester, by B. O’Connor, 2010, New York, NY: Square Fish. Copyright 2010 by Macmillan. Reprinted with permission.

Disability

The Schneider Family Book Awards , given annually by the ALA, “honor an author or illustrator for a book that embodies an artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences.” The award is given to books in three categories: picture books, middle-grade novels, and young adult novels.

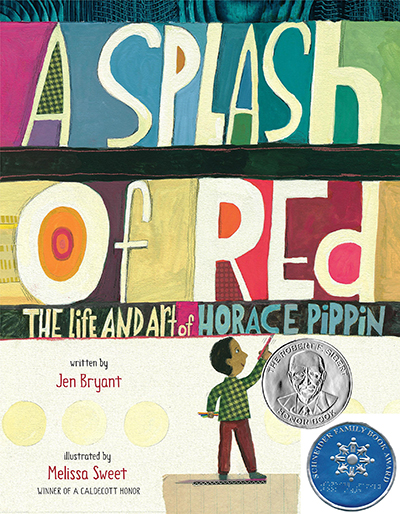

One picture book exemplar is A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin by Jen Bryant (see Figure 6), documenting the artist’s ability and determination to continue painting after he was shot in one arm during World War I.

Figure 6: Cover of A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin by Jen Bryant

Note: From A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin, by J. Bryant, 2013, New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. Copyright 2013 by Random House. Reprinted with permission.

As there are multiple aspects to our identities, there are also a number of ways in which we can see ourselves reflected. For instance, a Latina/o child and an African American child could both be autistic.

Reading a book like Rain Reign by Ann M. Martin, about a fifth grader with autism, could be a mirror in regards to disability but not necessarily race because the main character seems to be white. This is one example of why it is no easy task to fill classroom libraries with books that will function as both mirrors and windows for as many students as possible.

Schneider Family Book Award winners over the years have featured characters with a range of disabilities, including autism, dyslexia, blindness, an inability to speak, and clubfeet. An awareness of this award might make teachers more conscious about sharing books about characters with disabilities.

Thinking about genres and subgenres

Just as it is important to think about cultural diversity, it is also important to think about exposing children to multiple genres (e.g., poetry, nonfiction, historical fiction, fantasy) as well as subgenres such as wordless picture books and graphic novels. There are a few awards given specifically for certain genres; reading award winners in specific genres is one way to expose students to different types of texts and their characteristics.

For example, the Robert F. Sibert Award is given annually to outstanding informational books. Given for the first time in 2001, this award honors the work of Robert F. Sibert, a longtime president of Bound to Stay Bound Books.

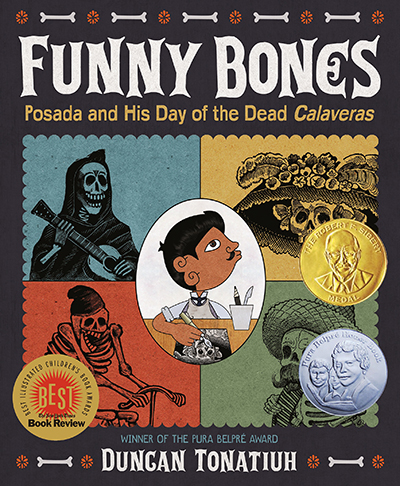

The 2016 Robert F. Sibert Award winner is Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras by Duncan Tonatiuh (see Figure 7), a biography of celebrated Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada.

Other notable winners/honors of this award over the past few years include Parrots Over Puerto Rico by Susan L. Roth and Cindy Trumbore, The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus by Jen Bryant, and Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement by Carole Boston Weatherford, which blends genres by telling about Hamer’s life through poetry.

There are also other awards for specific genres, such as poetry, nonfiction, and historical fiction, including the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award , the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children , the NCTE Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children , and the Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction .

Figure 7: Cover of Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras by Duncan Tonatiuh

Note: From Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras, by D. Tonatiuh, 2015, New York, NY: Abrams. Copyright 2015 by Abrams. Reprinted with permission.

How to stay informed

Although maintaining a diverse library may seem like a daunting task, there are several steps that you can take to accomplish this goal. The first step might be to take a close look at your existing classroom library to see if a good selection of books written by people of color is included in the library all year long, not just at certain times such as Black History Month.

Second, it is also important to consider where your books are purchased, because at times, our selections are influenced by what is readily available. Note that the Scholastic Reading Club, for example, offers cheaply priced titles, but a close analysis of book club order forms over time (McNair, 2008) revealed a lack of books written by and about people of color. Not surprisingly, one of the authors who appeared most often in the book club order forms was Eric Carle.

Ordering from book clubs is certainly appropriate, but it is necessary to supplement books by authors like Carle by purchasing racially diverse titles from other sources such as Amazon or Book Outlet , a discount outlet that has a good selection of racially diverse books across genres. Book Outlet regularly features books by authors and illustrators such as Kadir Nelson, Nikki Grimes, Yuyi Morales, Gary Soto, Angela Johnson, Yumi Heo, and Eloise Greenfield.

A third step, as mentioned earlier, is to learn about awards, some of which are race-based as well as others, such as the Schneider Family Book Award, that are not. Numerous professional organizations, such as the International Literacy Association, NCTE, and ALA, give awards.

Consider tuning in to watch the ALA’s annual Youth Media Awards announcement. It’s an exhilarating experience for those of us with a passion for children’s literature. Thousands of librarians attend the ALA midwinter conference and are able to be present at the press conference while others across the country watch a live webcast of the proceedings.

The press conference usually lasts about an hour, with the Newbery and Caldecott medals — considered the organization’s oldest and most prestigious — saved for last to build excitement. Learning about the various awards presented and each year’s winners serves as one important way in which we can make sure that our collections of books — whether we are educators, teacher educators, or librarians — are diverse in a number of ways.

Finally, to stay informed about notable titles being published, consider subscribing to reputable magazines that review books, such as The Horn Book Magazine and The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books . Reading reviews will allow for consideration of race, class, disability, religion, genre, and other factors.

Conclusion

Although it may be challenging to take on this task, the benefits are worthwhile. It is also important to remember that simply putting these books in our libraries is not enough. Reading them and sharing our enthusiasm with students is essential so they will seek out these books in the libraries.

Having a diverse collection can support all students in finding titles that they can read and connect with on some level while affirming their own cultural identities and hopefully developing important positive insights about others. We all need mirrors and windows in the books that we read.

About the author

Jonda C. McNair is a professor of literacy education at Clemson University, SC, USA; e-mail [email protected].

Jonda C. McNair, #WeNeedMirrorsAndWindows: Diverse Classroom Libraries for K–6 Students. The Reading Teacher Volume70, Issue3, November/December 2016, pages 375-381.