Abstract

Inferential comprehension requires both emotional intelligence and cognitive skills, however instructional comprehension strategies typically underemphasize the emotional contribution. This article documents an intervention used by diverse third grade students which centers on teaching story comprehension through character perspective-taking (i.e., Theory of Mind).

The intervention guides readers to identify the feelings and thoughts of two characters engaged in a conflict, and then analyze how their internal state drive their actions. As an alternative to a traditional story map, the authors created the graphic organizer, CHAMP: Chart for Multiple Perspectives.

Additional topics include selecting authentic children’s literature to support perspective-taking, employing the use of text evidence, and strategies for teaching emotional vocabulary. Implications for academic and social-emotional learning (e.g., empathy), cross-curricular extensions, and alignment to curricular standards are noted.

“How do you guide students to enter the world of a story, empathize with characters, and understand opposing viewpoints? Approaching comprehension from characters’ perspectives puts a new lens on instruction.”

Pause and Ponder

- What type of characters (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age) do your students connect with most easily? How can you support students to identify with characters who differ from them?

- How would it impact students’ social development to “take the perspective” of spiteful or pathological characters? How can you minimize any potentially negative effects?

- Under what conditions are your students able to consider the perspectives of teachers and peers?

- How can you support transferring social skills gained in reading to “real-life” conflicts?

Why read literature? Inspiration… Escape… Class assignment? While all are valid reasons, literary researcher Miall (2006) contends that literature has staying power because it “invites us to consider frames for understanding and feeling about the world that are likely to be novel” (p. 3). In other words, stories help us understand the social world in new ways. Miall (2006) labels this process of adopting new perspectives as “to dishabituate.” In the opening conversation of this article, Belinda (all names are pseudonyms) recognized that Max—who, despite his brothers’ teasing, continued to collect words (instead of “normal” things like stamps or coins)—was, in fact, brave. Then, through her recognition of Max’s bravery, Belinda reframed her experiences and defined herself as brave. This empathy with Max, which transcended gender, ethnicity, and reality, was likely affirming for her self-concept. She also gained understanding about how her teacher experienced a similar situation. It is important to note, due to the tone of Belinda’s voice, that she obviously drew upon her emotions as much as logic.

We advocate that, in the way informational texts teach readers about science or politics, literature teaches readers about the social world and how to navigate through difficult emotions and inevitable conflicts. Emerging evidence from cognitive psychology indicates that “just as computer simulations have helped us understand perception, learning, and thinking, stories are simulations of a kind that can help readers understand not just the characters in books but human character in general” (Oatley, 2011, p. 63). Returning to the idea of dishabituation, through stories readers can also try out, without personal risk, new reactions and social decisions. Young readers can then use that learning to navigate their current world of peer friendships and classroom conflicts.

However, to gain social understanding from fiction, we must consider characters’ internal experiences in addition to plot because “just as in real life, the worlds of literary fiction are replete with complicated individuals whose inner lives are rarely easily discerned but warrant exploration” (Kidd & Castano, 2013, p. 377). Unfortunately, because they must guide their students’ comprehension while keeping within time constraints, teachers may feel pressured to overemphasize plot events and spend little time exploring complex characters. Additionally, the most common instructional tool for story comprehension, the story map, depicts comprehension as a sequence of escalating plot events with little attention to characters’ thoughts and feelings (Smolkin & McTigue, 2015).

Therefore, it is essential that we provide students with comprehension strategies for stories that emphasize both the structural elements (setting, plot, climax) and the characters’ internal experiences. To date, there are limited teaching tools for such a goal. Our contribution is the Chart for Multiple Perspectives (CHAMP), an alternate graphic organizer for the traditional story map, which promotes inferential comprehension through the consideration of stories via the lenses of opposing characters.

Chart for Multiple Perspectives (CHAMP)

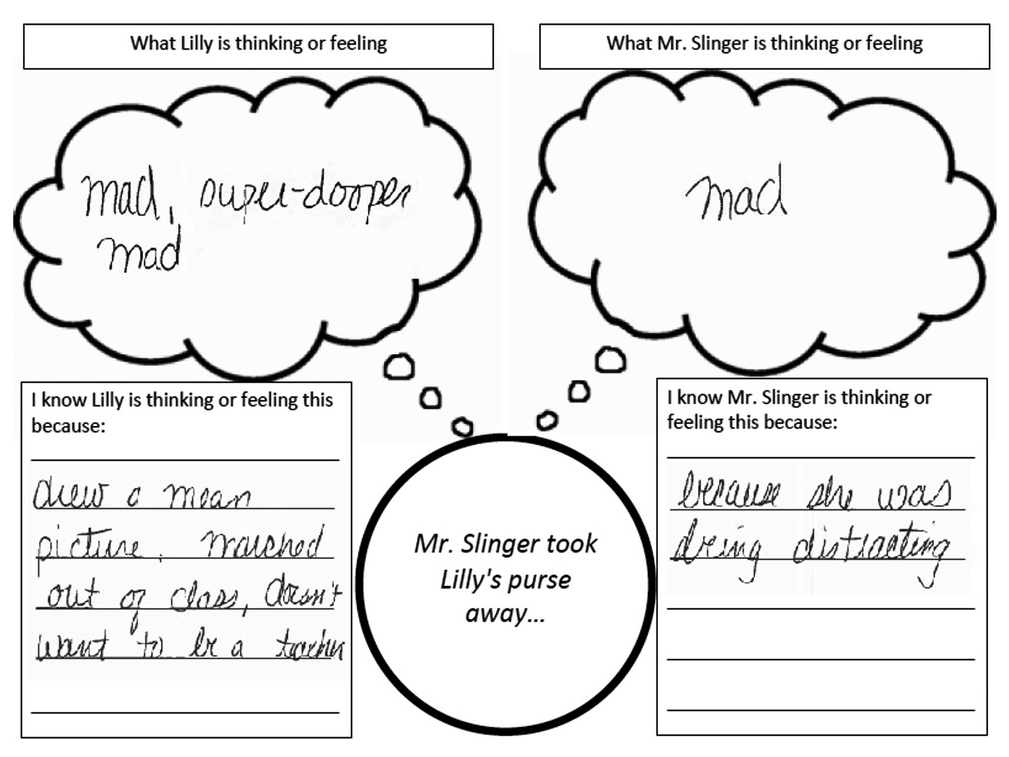

To create a graphic organizer that more clearly highlights the connection between what characters think and how they feel (i.e., their internal states) and their actions (i.e., their external choices), we started with Emery’s (1996) Story Maps with Character Perspectives and Shanahan and Shanahan’s (1997) Character Perspective Chart. Then, to place more attention on internal states, we borrowed “thought bubbles” from comprehension interventions designed for children on the autism spectrum (Gately, 2008). Each CHAMP graphic organizer focuses on one significant plot event in a story. The CHAMP graphic organizer is shown in Figure 1 documents a scene from Henkes’s Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse (1996). Although both characters are labeled as being mad, the evidence selected is unique to each character. Certain evidence came directly from the character’s behavior (e.g., Lilly drew a mean picture), while other information was inferred from the situation and likely based on experience (e.g., teachers can get mad when a student is distracting others).

Figure 1. CHAMP Graphic Organizer Completed From Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse

The target event is written in the center circle, to which two thought bubbles are connected. The student describes in the thought bubbles what each character is thinking or feeling. Next, in the boxes, the student provides evidence from either text or illustrations to explain these inferences. By completing a sequence of CHAMP graphic organizers while reading, not only do students construct a sequence of plot events, they simultaneously focus on the deeper understanding of the characters driving the plot. In our instruction, the intervention teacher selected three key plot events that roughly (1) introduced the main conflict, (2) escalated the conflict, and (3) resolved the conflict.

The CHAMP graphic organizer can also be used for various levels of learners. For students who are still learning about basic story structure, these graphic organizers can supplement a traditional story map. Additionally, as students’ skills develop, CHAMP graphic organizers can be distributed without the plot events identified. Students themselves can determine which plot events are most critical.

Why the current focus on literature and perspective-taking?

Before proceeding further, we briefly present the status of literature in elementary classes and build a case for increased attention on literature.

Literature in elementary classrooms: thriving or endangered species?

According to Shanahan (2012), a well-circulated urban legend regarding the Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010) is that schools must abandon literature in favor of informational texts. As written, the standards advocate for an even balance of informational text and literature in the elementary grades. Specific standards reveal a close match between our instructional recommendations and the English language arts CCSS. For example, in grade 2, students are expected to “describe how characters in a story respond to major events and challenges” (RL.2.3). The analogous expectation in grade 3 links internal states to the plot: “Describe characters in a story…and explain how their actions contribute to the sequence of events” (RL.3.3). Then, in grade 4, students must provide evidence: “Describe in depth a character, setting, or event in a story or drama, drawing on specific details in the text” (RL.4.3).

However, prior to the CCSS, the picture storybook had lost privileged status in many elementary classrooms. Since the report of the National Reading Panel (NRP) in 2000, the recommended reading curriculum emphasized that students are reading within a precise instructional range. In practice, this often resulted in selections from leveled anthologies or bins filled with decodable readers classified as “easy,” “just right,” and “too hard.” Unfortunately, such overly structured reading curricula left limited time for picture book reading (Serafini, 2011) because picture books’ quantitative readability levels are generally not “just right” for elementary readers. For example, due to rich (i.e., nondecodable) vocabulary and complex sentences, 50 years of Caldecott winners have an average readability score of approximately fifth grade (Chamberlain & Leal, 1999). However, as Allington (2005) and others have clarified, the NRP report did not recommend exclusive use of decodable texts because “basically no studies existed in which decodable texts had been isolated as a variable to estimate their impact on reading acquisition. None” (p. 465). As a potential correction, the CCSS recommend that students should not be frequently frustrated but should have regular opportunities to experience more sophisticated reading (Shanahan, 2012). Although dependent on interpretation and local implementation, the CCSS may provide more room for authentic literature.

However, adding to the problem of literature’s declining status in the elementary reading curriculum is the fact that the empirical work on comprehending children’s literature has typically been restricted to traditional plot elements rather than layered interpretation (Sipe, 2000; Smolkin & McTigue, 2015). Meanwhile, in English departments, scholars focus on how an idealized reader interprets literature rather than how regular readers experience fiction (Miall, 2006). Additionally, both groups have not incorporated recent findings from psychology regarding the connection between fiction and readers’ emotional development (see Oatley, 2011, for an overview). Therefore, empirically establishing that literature has essential roles in the elementary classroom—and in child development—can help reassert its status.

Why is comprehension instruction via perspective-taking important?

Understanding literature and understanding people draw from many of the same skills, particularly due to perspective-taking, more precisely termed as theory of mind (Pelletier & Astington, 2004). Consequently, readers both use real-life experiences to understand story characters and use insight from the imagined world of story characters to better navigate their real world. For example, adults who frequently read fiction show stronger empathy than readers of nonfiction (Mar, Oatley, & Peterson, 2009). Even more surprisingly, interventions requiring adults to read literature can improve empathy skills (Djikic, Oatley, & Moldoveanu, 2013). In short, the stereotype of the antisocial bookworm is being debunked (Mar, Oatley, Hirsh, dela Paz, & Peterson, 2006).

Unfortunately, limited research has explored how literature can help develop children’s social skills, although Lobron and Selman (2007) advocate that perspective-coordination taught through literature provides a foundation for social awareness. This idea shares features with bibliotherapy (e.g., Pehrsson, 2005), when stories are used to help children cope during traumatic events such as losing a parent. Bibliotherapy usually addresses a crisis, however. In contrast, we advocate that fiction can also be used proactively as a training ground to practice perspective-taking and conflict analysis. Ideally, students can use insight from fiction to build interpersonal skills that allow them to resolve, rather than escalate, conflicts.

Perspective-taking skills also directly support literacy development, particularly higher order comprehension and motivation. Accordingly, Chall’s (1983) Stage Four of literacy development is reading for multiple viewpoints in literature and informational texts. Inferential comprehension clearly demands using knowledge beyond the text to understand characters’ actions and motives. Beyond that, critical literacy then requires readers to consider questions such as “What view of the world is put forth by the ideas in this text? What views are not?” (Cervetti, Pardales, & Damico, 2001). Such challenging questions demand that readers consider others’ goals, particularly the author’s. A recent meta-analysis shows that even simply instructing readers to take alternate perspectives while reading narratives can improve comprehension (Yeh & McTigue, 2013).

Finally, because engagement for reading is an emotional state, reading instruction should consider both cognitive skills and emotions to build motivation (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Therefore, if we can help students connect with characters through perspective-taking and empathy, it provides motivation to persist. Simply put, students will want to know what happens in the end!

What theories support this intervention?

While many theories influence this work, primarily we drew from Miall and Kuiken’s (2002) reader response theory, which argues that prevalent cognitive models of comprehension (e.g., construction-integration theories) do not fully explain the role of emotion in fiction comprehension. However, as this theory has been predominantly applied to adults, we consulted stage models of development — specifically, Selman’s (2003) Developmental Model of Perspective-Taking — to create appropriate expectations.

How do we teach comprehension via perspective-taking with literary texts?

Selecting the literature for perspective-taking

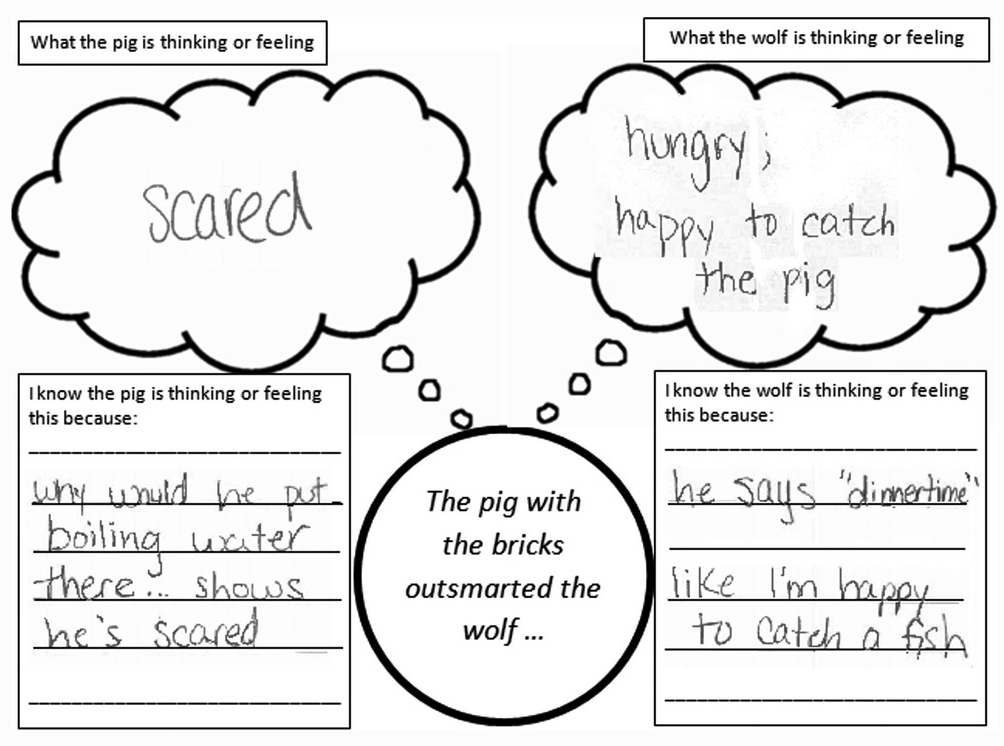

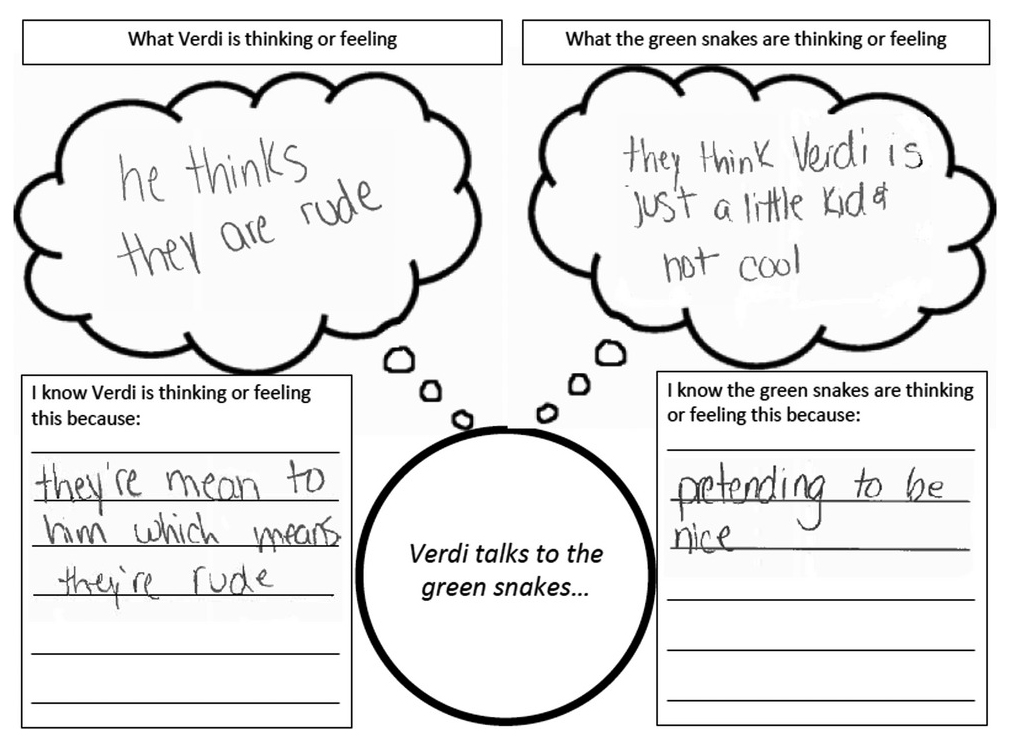

As this intervention’s success is fully contingent on the texts, we reviewed hundreds of books and ultimately developed five guiding questions for literature selection (see Table 1) that work well with the CHAMP graphic organizer. Toward the goal of scaffolding, we sequenced the lessons to start with more simplistic stories, such as the traditional fable The Three Little Pigs (Marshall, 1989), then transition to more sophisticated texts such as Verdi (Cannon, 2006). As can be seen in Belinda’s two CHAMP graphic organizers (Figures 2 and 3), the simpler tales were easier to deconstruct. In The Three Little Pigs, the evidence was often physical, such as the boiling water. In Verdi, the evidence provided was more subtle. While Belinda’s inferences about the characters’ feelings are accurate to the story, she has more difficulty identifying clear evidence in Verdi.

Table 1. Guiding Questions for Book Selection

| Guiding Question | Explanation | Example or Nonexample |

|---|---|---|

| Is the plot driven by an interpersonal conflict? | The main conflict must be between two characters, and the plot events must derive directly from that conflict. We started with traditional tales and moved to more complex plots. | The plot of Tortoise and the Hare surrounds the conflict of Tortoise and Hare both intending to win a race. |

| Are characters relatable and well developed? | Based on Horning (2010), we looked for a range of emotions and for each major character having a few consistent personality traits. | Lilly in Henkes’s Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse expressed many emotions and even demonstrated slightly contradictory behaviors. |

| Is inferential reasoning required for determining character motives? | The text provides multiple clues about characters’ motivations but does not explicitly state their feelings. | A nonexample is Judith Viorst’s Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, Very Bad Day because Alexander says exactly how he feels. |

| Does the book contain quality illustrations that support comprehension? | Based on interventions with children on the autism spectrum (Gately, 2008), we primarily analyzed the extent that characters’ facial features and bodies revealed information about their thoughts and feelings. | Students particularly appreciated Leonardo the Terrible Monster by Mo Willems for the characters’ expressions and the way that the words’ colors and shapes reflected the characters’ moods. |

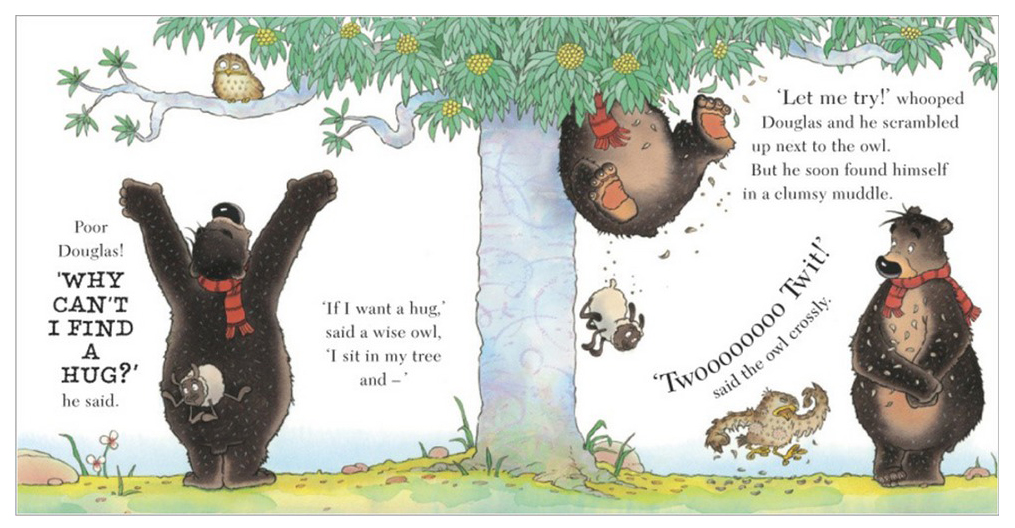

| Is the story engaging and appropriate for the grade level? | While this criteria is highly subjective, we looked for texts that evoke a major theme about life that students could relate to (e.g., acceptance into a group, fear of trying something new). Additionally, we sought out humorous texts. | Hugless Douglas by David Melling was a favorite for the humor, the illustration style, and the relatable theme that Douglas only wanted a hug! |

Figure 2. CHAMP Graphic Organizer Completed from The Three Little Pigs

Figure 3. CHAMP Graphic Organizer Completed from Verdi

Additionally, we used one text with a deliberate perspective switch: The True Story of the Three Little Pigs (Scieszka, 1989), which is told from the Wolf’s point of view. This book was interesting because the Wolf is a compelling yet potentially unreliable narrator. However, students tended to be fully convinced of his version of the story. For example, when we asked David if he believed the Wolf, he confidently said, “Yes, because he seems nicer than the pigs.”

Following the intervention, we asked the participating students to revisit the whole set of texts and provide input as to which books we should continue to use or not. We also conducted interviews about their favorite texts. Based on students’ input, we compiled a Top 10 list and summarized their rationales (see Table 2).

Table 2. Top 10 Student-Rated Books for Perspective-Taking

| Title | Conflicts | Engagement Factors Reported in Student Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Chrysanthemum by Kevin Henkes | Chrysanthemum vs. Classmates | Students engaged deeply, and they easily related to Chrysanthemum as she coped with being teased for her unique name. |

| Hugless Douglas by David Melling | Douglas vs. secondary characters | Students enjoyed the interplay between the text and the illustrations. The text worked as an additional visual support for communicating the main themes of the story. |

| Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse by Kevin Henkes | Lilly vs. Mr. Slinger | Students related to Lilly’s interaction with her teacher, first by getting into trouble, then by acting out, and finally by accepting responsibility. |

| Ruby the Copycat by Peggy Rathmunn | Ruby vs. AngelaRuby vs. Miss Hart | Students found that the behavior of one friend mimicking another in order to be “cool” was highly relatable. |

| Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type by Doreen Cronin | Cows vs. Farmer Brown | Students found the plot and cartoonlike pictures entertaining, and they enjoyed the onomatopoeia-type vocabulary and the interplay between text and illustrations. |

| Leonardo the Terrible Monster by Mo Willems | Leonardo vs. Sam | Students noticed and were interested in how the author presented the text with different fonts and sizes to match how Leonardo and Sam were feeling. |

| The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Pinkwater | Mr. Plumbean vs. his neighbors | Students appreciated the psychedelic illustrations and inferred how the colors matched the story (darker colors when Mr. Plumbean was fighting with neighbors and brighter colors when they got along). |

| Verdi by Janell Cannon | Verdi vs. the older snakes | Students related to the courageousness of Verdi, who stood up to the older snakes when they teased him. |

| Max’s Words by Kate Banks | Max vs. his brothers | Students related to Max, who wanted to be like his older siblings. They were intrigued by his collection of words and enjoyed searching for new vocabulary words throughout. |

| Duck & Goose by Tad Hills | Duck vs. Goose | Students enjoyed the appealing illustrations and the absurdity of both Duck and Goose, who believed a beach ball was an egg. |

Why so many animal characters?

As is evident in our Top 10 list, the majority of the texts feature animal characters. This was not our original intent. We purposefully worked to locate books with diverse people characters. For example, we prioritized Juanita Havill’s Jamaica Tag-Along (1990) and John Steptoe’s Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters: An African Tale (1987) because both texts feature strong female protagonists who are ethnically underrepresented. However, our search proved difficult because many multicultural texts, appropriate for the other requirements of this intervention, were chapter books. This issue was also noted by Lobron and Selman (2007). They used the chapter book Felita by Nicholasa Mohr (1991), an immigration story, for developing social awareness; however, to adapt the intervention to younger children, they observed that appropriate texts for younger children were frequently written with animal characters.

The prevalence of animals as characters can be explained by two key points. First, animal characters allow for the most readers to be able to connect similarly to the characters. Secondly, people characters are not commonly used for children’s books reflecting interpersonal conflict because the use of animals allows the author to “eliminate or circumvent several important issues that are otherwise essential in our assessment of character: those of age, gender, and social status” (Nikolajeva & Scott, 2001, p. 92). We suggest that race and ethnicity should be added to this list. For our intervention, the animal characters worked well; the students focused less on surface characteristics and more on the underlying conflict. However, we would recommend using a range of books that ideally has both animal characters and realistic diverse, complex people characters to help transfer readers’ learning to the real world.

Lesson framework and evidence of impact

We view the CHAMP graphic organizer as a tool to foster interaction about literature. The organizer served as a during-reading activity in a larger lesson cycle: (a) introduce key vocabulary (including emotion vocabulary); (b) read the text and complete the graphic organizer; (c) discuss the text during and after reading; and (d) complete a formative assessment, in the form of a summary/retelling and comprehension questions. As the very goal of this type of instruction is to gain insight and coordinate multiple perspectives, teacher and peer sharing represent the core mode of learning. While we worked in a one-on-one tutoring situation, this framework would be even better suited for small-group instruction, which would allow for richer discussion. (See Take Action! sidebar for examples.)

Using a gradual release approach, in the first lesson, we modeled how to complete the CHAMP graphic organizer. Then, for three weeks (15 lessons), we had the students complete the CHAMP graphic organizer on their own, but we used sticky notes to designate stopping points throughout each story. The discussions were frequently teacher-directed, although we encouraged more student leading as the lesson progressed. After three weeks, we stopped requiring the CHAMP graphic organizer and let the students read books independently, and we continued to measure their comprehension.

Removing this support let us observe whether the students had internalized the thinking strategies facilitated by the graphic organizer. Using Afflerbach, Pearson, and Paris’s (2008) skill versus strategy definitions, we aimed to introduce the CHAMP graphic organizer (and the approach of reading for multiple perspectives) as a strategy, but our longer-term goal was for this approach to become an internalized skill.

Based on Emery’s work (1996), we prompted discussion after reading by using general, open-ended question stems that emphasize characters’ thoughts and feelings. By varying the underlined components, the same questions can be adapted to most stories (see Table 3). Using consistent question stems helps students internalize the questions; it also makes planning easy and allows teachers to track students’ growth over time. Additionally, the subjective questions encourage multiple interpretations and ensure that the discussions are not simple summaries. Rather than focusing on correctness, we aimed for students to use text evidence, make text-to-self or text-to-text connections, and demonstrate clear communication of ideas, particularly emotions. We tracked progress with a holistic rubric that gave scores of 0–3 points per question.

Table 3. Rubric for Inferential Comprehension of Characters’ Thoughts and Feelings

Substitute story specifics for the underlined words in question stems

- Why did the character do an action?

- How did the character feel about an event?

- What did the character think when the event occurred?

- What did the character want from the event?

- In this story, what did the character want most of all?

| Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 0 | The answer is inconsistent with the story. |

| 1 | The answer is potentially correct, but the student does not demonstrate perspective-taking (of internal states), provide relevant connections to his or her own life (i.e., text-to-self connections), OR suppoly text evidence (including from illustrations). |

| 2 | The student correctly answers the question, demonstrating or providing ONE of the following: (a) perspective-taking, (b) connection to his or her own life, (c) text evidence. |

| 3 | The student correctly answers the question, demonstrating or providing MORE THAN ONE of the following: (a) perspective-taking, (b) connection to his or her own life, (c) text evidence. |

Through daily monitoring, we observed regular, incremental growth in students’ inferential comprehension and greater sophistication of understanding characters’ thoughts and feelings (see Hodges et al., 2014). While students’ performance varied by story (and by their interest in the story), the overall trend persisted. After 15 lessons, this intervention showed modest evidence of skill development through the comprehension question scores. From qualitative evidence, by the end of the intervention, students approached new texts with a greater focus on characters’ motivations (instead of plot events) and were more excited to read stories.

Differentiating perspective-taking instruction

As we worked with each of our students, we adapted instruction for their needs. Supporting strategies emerged: teaching emotional vocabulary, using text evidence, and using picture evidence.

Teaching emotional vocabulary

We soon realized the need to nurture students’ emotional vocabulary beyond the primary feelings of sad, mad, and happy. After we began explicitly teaching emotional vocabulary, students were able to discuss their inferences about characters’ internal states with greater precision and fluency—particularly Belinda, an English learner. Belinda was performing modestly well in comprehension but was not showing growth. However, her intervention teacher observed that Belinda was limited by her vocabulary to describe emotions and would often present a scenario rather than an emotion. For instance, instead of saying annoyed, she said, “I’d feel like that if someone was just, like…just throwing things at me on purpose.” Rather than saying surprised or shocked, she described the character as “feeling like a big bomb went off.” While Belinda was able to convey feelings creatively, her work-around descriptions were also rather effortful. Therefore, we inferred that Belinda’s emotional intelligence was much higher than her emotional vocabulary.

Our instruction took minimal time. We used Feelings Flash Cards created by children’s author/illustrator Todd Parr (2010; see Figure 4). Before reading, Belinda’s intervention teacher presented four new emotions and provided a student-friendly definition. Then, as recommended by Nikolajeva (2013), Belinda and her teacher observed the pictures’ facial cues and body language. Next, the teacher reviewed previously learned emotion words in the manner of Kucan’s (2012) Generating Situations game, in which teacher and student both created scenarios to evoke various words, such as “How would you feel if the principal hung your painting in her office?” and “When do you feel peaceful?”

Figure 4. Sample of Todd Parr’s Feelings Flash Cards

An excerpt from a conversation about Leonardo the Terrible Monster by Mo Willems (2005) shows an example of how Belinda began trying out diverse and specific emotion words, including shocked, frightened, and brave.

Using text evidence

David, an African American boy, struggled with both fluency and comprehension but displayed a vivid imagination and demonstrated great insights during the reading process. However, he frequently had difficulty answering comprehension questions at the end of the story and usually provided a single-word answer. After a few lessons, his teacher noted his strengths and explained that, as a next step, David would now be responsible for proving each answer with text evidence (including from illustrations). The intervention teacher indicated that even a “correct” answer was incomplete without evidence to back it up. She modeled how to do this in multiple ways, then prompted David after reading. This proved useful right away and helped David expand from one-word answers to multiple sentences.

Using picture evidence

Illustrations were central to discerning characters’ thoughts and feelings, and we used illustrations in multiple ways. First, we always cued students to find evidence by asking, “Is there anything in these pictures or words that tells you how the character is feeling?” Additionally, because we taught emotional vocabulary through analyzing the pictures on Feelings Flash Cards (Parr, 2010), students were primed to examine the illustrations in a similar manner.

We observed students regularly doing this. Most commonly, students frequently used facial clues as evidence. For example, while reading Too Many Toys (Shannon, 2008), Belinda observed how the boy felt: “I know because on the picture, he is shocked ‘cause his mouth is so big and eyes popping OUT. Like, ‘What are you saying, woman?’ He is shocked!” Then she used body language to give evidence for his mom feeling tired: “She’s kind of flopped down on the floor all flat. Like, sometimes when I am exhausted, I just fall down and go to sleep sometimes like that. She is tired and just wants to go to sleep and not deal with toys.”

The students also noted aspects of the illustration design that gave more indirect clues about characters’ states of mind. For example, in Leonardo the Terrible Monster (Willems, 2005), the boy Leonardo targets is already the nervous sort. Ariel (also an English learner) explained that the boy looked scared because he was presented so small. She said, “They should have drawn him bigger. Not hiding in the corner.”

One less expected aspect of illustrations that the students cued into was what we called integrated word art, meaning when the font and arrangement of the words also communicated meaning and emotion. David was the first student to point this out to us, referring to why he liked Hugless Douglas (Melling, 2010). He told his teacher, “Because I like big words and silly words!” and then pointed out examples of how the text and pictures were mixed together in the page (see Figure 5). For example, the owl’s anger can be seen in how his loud words jump up the page.

Figure 5. Sample of Integrated Illustration and Text from Hugless Douglas

Extensions

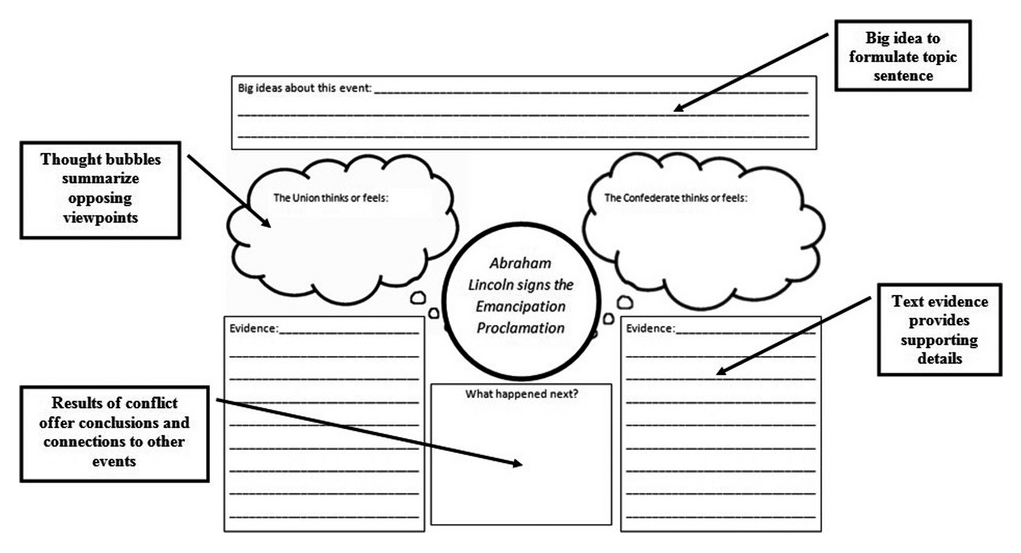

While perspective-taking for comprehension is uniquely suited to stories, the benefits of understanding multiple perspectives and critical literacy is not limited to fiction. Reading in content area classes frequently requires readers to consider opposing arguments and motivations, and the CHAMP graphic organizer is easily adapted to this purpose. For example, history frequently uses timelines and flow charts to organize classroom content. Incorporating perspective-taking graphic organizers facilitates connections between historical figures. A graphic organizer structured like a character thinking map helps students to describe two sides of a debate and provide evidence for both arguments, such as Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Sample CHAMP Graphic Organizer Used in History

Final thoughts

We encourage teachers to approach narrative comprehension instruction from the perspective of multiple characters. Having students consider how opposing characters are feeling and what they are thinking can result in lively and productive discussions. Then, teachers should challenge students to make connections between the characters’ internal states and their actions in the plot. This approach can be integrated into an ongoing reading curriculum, introduced through class read-alouds, or incorporated into select content area reading. Graphic organizers, specifically CHAMP, can help make the process more visible.

While challenging for elementary students, this pathway helps students to become emotionally engaged and invested in the fate of characters in the texts they read. Additionally, the skills honed by perspective-taking practice transcend story reading and support reading in other areas of school. The positive impacts can be both social (e.g., fostering perspective-taking to resolve peer conflicts) and academic (e.g., helping students understand multiple sides of a scientific debate).

Take action!

| Step | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Identify appropriate picture books. | Select engaging picture books with plots driven by interpersonal conflicts. | Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse by Kevin Henkes (1996) |

| Step 2: Identify stopping points. | Prior to instruction, identify two to three conflicts in the text that can serve as stopping points for discussion of character perspective. | Lilly ignores her teacher’s instructions to not play with her new purse during class. |

| Step 3: While reading, pause at stopping points and ask probing questions about characters’ feelings. | Pause at the stopping points and ask students what they believe characters are thinking or feeling at that moment. Be sure to discuss both sides of the conflict and have children justify their responses with evidence from the text and illustrations. | What is Mr. Slinger thinking or feeling when Lilly doesn’t follow his instructions? How do you know?What is Lilly thinking or feeling when Mr. Slinger takes her purse away? How do you know? |

| Step 4: Fill in CHAMP graphic organizer. | Transcribe character thoughts or feelings into thought bubbles and text evidence into boxes. | |

| Step 5: Allow for further discussion between the students and teacher as necessary. | During or after completing the graphic organizer, students may want to engage in additional conversations about the characters, their motives, and the sequence of plot events. Teachers can encourage these discussions to promote deeper comprehension and further perspective-taking. | The students may relate the incident of Lilly and Mr. Slinger to a time they got in trouble during class. Help students use this analysis to make predictions. |

Mctigue, E., Douglass, A., Wright, K. L., Hodges, T. S., & Franks, A. D. (2015). Beyond the Story Map. The Reading Teacher, 69(1), 91-101. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1377