Fluency means reading faster, smoother, more expressively, or more quietly with goal of reading silently. Fluent reading approaches the speed of speech. Beginning readers usually do not read fluently; reading is often a word-by-word struggle.

How do we help children struggling with slow, painstaking sounding out and blending? Support and encourage them. Effortful decoding is a necessary step to sight recognition. “I know reading is tough right now, but this is how you learn new words.” Ask them to reread each sentence that requires unusual decoding effort.

In general, the fluency formula is: Read and reread decodable words in connected text. Decode unknown words rather than guessing from context. Reread to master texts. Use text with words children can decode using known correspondences. Use whole texts to sustain interest.

There are two general approaches to improving fluency. The direct approach involves modeling and practice with repeated reading under time pressure. The indirect approach involves encouraging children to read voluntarily in their free time.

The direct approach: Repeated readings

We often restrict reading lessons to “sight reading.” Who could learn a musical instrument by only sight-reading music and never repeating pieces until they could be played in rhythm, up to tempo, with musical expression?

In repeated reading, children work on reading as they would work at making music: They continue working with each text until it is fluent. Repeated reading works best with readers who have reached at least a primer instructional level. Use a passage of 100 words or so at the instructional level. The text should be decodable, not predictable. The reader might select a favorite from among familiar books.

Two ways to frame repeated reading:

- Graph how fast students read with a “1 Minute Read.” Graphing is motivating because it makes progress evident. Emphasize speed rather than accuracy. Set a reachable but challenging goal, e.g., 85 words per minute. Have the student read for 1 minute. Count the number of words read and graph the result with an easily understood chart, e.g., move a basketball player closer to slam dunk.

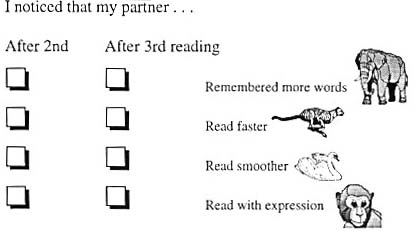

- Use check sheets for partner readings. With a class of children, pair up readers to respond to one another.

Begin by explaining what you’ll be listening for; model fluent and non-fluent reading. For example, show the difference between smooth and choppy reading. Show how expressive readers make their voices go higher and lower, faster and slower, louder and softer.

In each pair, students take turns being the reader and the listener. The reader reads a selection three times. The listener gives a report after the 2nd and 3rd readings. All reports are complimentary. No criticism or advice is allowed.

The indirect approach: Voluntary reading

Sustained silent reading (SSR, a.k.a. DEAR, “drop everything and read”) gives children a daily opportunity to read and discover the pleasure of reading. Each student chooses a book or magazine, and the entire class reads for a set period of time each day.

SSR has been shown to lead to more positive attitudes toward reading. In addition, the use of peer discussion groups with SSR leads to gains in reading achievement. When students share their reactions to books with classmates, they get recommendations from peers they take seriously.

Tierney, Readence, and Dishner, in Reading Strategies and Practices (Allyn & Bacon, 1990, pp. 461-462) list three “cardinal rules” for SSR:

- Everybody reads. Both students and teacher will read something of their own choosing. Completing homework assignments, grading papers, and similar activities are discouraged. The reading should be for the pleasure of the reader.

- There are to be no interruptions during USSR. The word uninterrupted is an essential part of the technique. Interruptions result in loss of comprehension and loss of interest by many students; therefore, questions and comments should be held until the silent reading period has concluded.

- No one will be asked to report what they have read. It is essential that students feel that this is a period of free reading, with the emphasis on reading for enjoyment.

Other essentials for encouraging voluntary reading include a plentiful library of books and frequent opportunities to choose. Children should be allowed and encouraged to read page turners (e.g., easy series books) rather than the classics for their independent reading. For gaining fluency, quantity is more important than quality.

Book introductions help children make informed decisions about what they want to read. For an effective booktalk, choose a book you like. Show the illustrations to the students. Give a brief talk, hitting the high points: the setting, characters, and the inciting incident leading to the problem or goal. Do not get into the plot, and especially not the resolution. If there is no clear plot, ask a have-you-ever question (e.g., Have you ever been afraid of the dark?) and relate the question to the book. Good booktalks often feature some oral reading, e.g., of a suspenseful part.

Excerpted from: Murray, B. (1999). Developing Reading Fluency. The Reading Genie, www.auburn.edu/~murraba/. Auburn University.