Many of our most vulnerable children attend the lowest quality programs, and children who are at risk for school failure are more strongly influenced by the quality of preschool. Many children from middle-class families also attend preschools that are not of good quality. Momentum is building across the country to develop more preschool programs. Therefore, it’s crucial to have a clear vision of what high-quality preschool programs look like.

Rating preschool quality

Preschool programs are typically rated on two dimensions of quality — process and structure. The interactions, activities, materials, learning opportunities, and health and safety routines are observed and rated as a measure of process quality. The second dimension, structural quality, includes the size of each group of children, the adult-child ratio, and the education and training of the teachers and staff.

The most widely used instrument for measuring process quality in early education programs shows that fewer than half the programs measured enjoy a “good” to “excellent” rating.

Dimensions of a high-quality preschool program

This brief uses the latest research findings and best practices recommended by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC)to describe the features of a high-quality preschool program in terms of what’s critical for the child, family, teacher, curriculum, and classroom.

It is commonly accepted that children who attend preschool are more likely to succeed in kindergarten than those who do not. Participating in early education can also provide academic and social benefits that last well beyond kindergarten. However, researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that for children — particularly children from low-income backgrounds — to benefit from preschool, it must be of high quality.

Two influential studies on the effects of intensive, high-quality early childhood programs have demonstrated that these programs benefit disadvantaged children academically and socially into adulthood. Unfortunately, research indicates most of America’s young children are not attending high-quality preschool programs. Most programs for which researchers have studied quality were rated below the minimum for a preschool program to be judged “good.”

Additionally, children from the lowest income families are found more likely to attend lower-quality programs. Children who are at risk for school failure benefit the most from good early education, but they are the least likely to get it. Furthermore, many children from middle-class families also attend preschool programs of mediocre quality.

It is imperative that policy makers work to raise the overall quality of preschool education, targeting America’s most vulnerable children first.

The research is clear that investing in high-quality preschool education will benefit children and is worth the cost. But before we make this investment, we must have a clear vision of what high-quality preschool programs look like.

How do we define and measure quality in early education?

This brief defines preschool as center-based programs that provide educational experiences for children during the year or years preceding kindergarten. They can be located in a child-care center, state pre-kindergarten, private preschool, or Head Start center.

In the United States, 76% of children ages three and four receive education and care from someone other than a parent. The majority (58%) attend a center-based program defined as preschool, child care, or Head Start. What do we know about the level of quality in these programs?

Two generally accepted approaches to measuring the quality of early childhood programs focus on process and structure.

Process quality

Process quality emphasizes the actual experiences that occur in educational settings, such as child-teacher interactionsand the types of activities in which children are engaged. Process measures can also include health and safety provisions as well as materials available and relationships with parents.

Process quality is typically measured by observing the experiences in the center and classrooms and rating the multiple dimensions of the program, such as teacher-child interactions, type of instruction, room environment, materials, relationships with parents, and health and safety routines. The Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS) has been widely used in early education research to measure process quality. The revised edition includes 43 items organized into seven areas of center-based care for children aged 2.5 through 5 years. The areas are: personal care routines, space and furnishings, language-reasoning, interaction, activities, program structure, and parents and staff. Each item has detailed descriptors and can be rated from 1-7, with (1) inadequate, (3) minimal, (5) good, and (7) excellent.

When the activities and interactions are rated higher, children develop more advanced language and math abilities, as well as social skills. Conversely, poorer process quality has been linked to increased behavior problems.

Furthermore, these benefits in cognitive and social development last well into the elementary years. A longitudinal study of the short- and long-term effects of center-based care on children’s development concluded: “High-quality child care experiences, in terms of both classroom practices and teacher-child relationships, enhance children’s abilities to take advantage of the educational opportunities in school.”

Structural quality

The second way to measure quality is to review the structural and teacher characteristics of the program, such as teacher-child ratios, class size, qualifications and compensation of teachers and staff, and square footage. The structural features of a program are thought to contribute to quality in more indirect ways than process features. Structural features are frequently regulated through state licensing requirements.

Researchers have consistently found that these two sets of indicators — process and structure — are related, and influence the quality of the educational experiences for children. For example, when groups are smaller, teachers tend to have more positive, supportive, and stimulating interactions with children. Warm and nurturing interactions are directly linked to children’s social competence and future academic success, and such interactions are essential to high quality. Early childhood teachers who are more highly qualified and have smaller groups can more effectively provide individualized, responsive learning opportunities. Finally, higher teacher wages have consistently been linked to higher process quality.

Ratios, an indicator of structural quality, are also associated with process quality. That is, higher ECERS scores are more likely in programs with lower child-teacher ratios.

What is the current quality of early education programs?

Although there are no nationally representative studies on the process quality of the average early childhood program, two multi-state studies and numerous smaller studies using the ECERS provide good estimates.

A 1998 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development study 15 of early care in nine states concluded that in early childhood settings for children through age three, 8% were rated “poor,” 53% “fair,” 30% “good,” and 9% “excellent” in process quality.

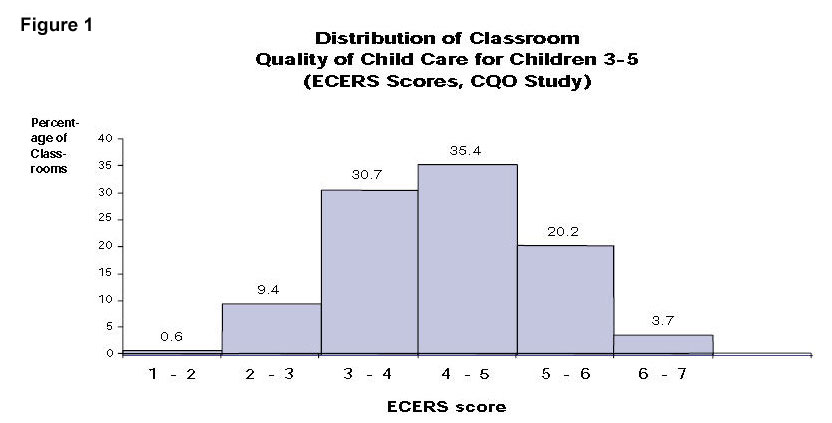

The Cost, Quality, and Outcomes Study (1999) examined full-day child-care centers in four states and found the average quality as rated on the ECERS to be 4.26 (on the 1-7 scale). In this large-scale study of typical programs, only 24% had total average scores in the “good” to “excellent” range. (See Figure 1 for distribution of scores.)

The essential indicators of quality preschool

Aspects of Process

- There are positive relationships between teachers and children.

- The room is well-equipped, with sufficient materials and toys.

- Communication occurs throughout the day, with mutual listening, talking/responding, and encouragement to use reasoning and problem-solving.

- Opportunities for art, music/movement, science, math, block play, sand, water, and dramatic play are provided daily.

- There are materials and activities to promote understanding and acceptance of diversity.

- Parents are encouraged to be involved in all aspects of the program.

Aspects of Structure

- Adult-child ratios do not exceed NAEYC recommendations.

- Group sizes are small.

- Teachers and staff are qualified and compensated accordingly.

- All staff are supervised and evaluated, and have opportunities for professional growth.

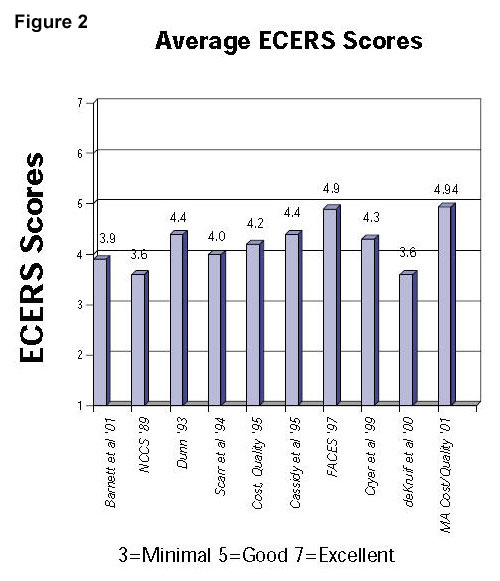

Other studies using the ECERS to measure process quality confirm these findings. In 10 studies across multiple states, the average overall ECERS score did not reach 5.0. (See Figure 2) The Massachusetts Cost and Quality Study (2001), which described the quality of community-based programs serving preschool-aged children, and the FACES study of a nationally representative sample of Head Start programs, reported average scores of “almost good” (just below 5.0), but most were in the “minimally adequate” range. While these findings create concern about the quality of experiences provided to most young children in typical programs, the Massachusetts report and FACES study of Head Start offer hope that large-scale programs can achieve good quality.

Critical for children

Children are respected, nurtured, and challenged. They enjoy close, warm relationships with the adults and other children in their classroom. They frequently interact and communicate with peers and adults; they do not spend long periods of time waiting, being ignored, or isolated. Children enjoy and look forward to school.

Children have ongoing opportunities to learn important skills, knowledge, and dispositions. Classrooms are busy with conversations, projects, experiments, reading and building activities. The materials and activities are individualized and challenge children’s intellectual development. Children do not wander aimlessly and they are not expected to sit quietly for long periods of time.

Children are able to make meaningful decisions throughout the day. They can choose from a variety of activities, decide what type of products they want to create, engage in important conversations with friends and exercise their curiosity.

The children’s home language and culture are respected, appreciated, and incorporated into the curriculum and the classroom.

Children participate in individual, small-group, and large-group activities. They learn important social and self-regulation skills through adult guidance and appropriate discipline. All children are not expected to develop at the same rate; individual needs and abilities are accommodated in all learning activities.

Children learn the skills necessary for future academic success. Language and literacy activities include frequent interactive book reading, expanded conversations with adults, opportunities to read and write throughout the day and a positive, joyful climate for learning. They have opportunities to learn the language of school — how to listen, follow directions, respond to teacher questions and initiate problem solving.

Children have the opportunity to learn basic school readiness skills. They learn expanded vocabulary, alphabetic principles, phonological awareness; concepts of numbers, shapes, measurement and spatial relations; task persistence; early scientific thinking; and information about the world and how it works.

Children’s natural curiosity is used as a powerful motivator. Their interest in everything in their environment as well as ideas and concepts contribute to the design of activities and curriculum.

Children are given variety in their daily schedule. A child’s day should allow for active and quiet time, indoor and outdoor time, short activities and longer ones to increase attention spans, and careful planning to address all aspects of development for all children.

Critical for families

Family members are included as partners in all aspects of the educational program. Families are routinely consulted about the interests, abilities, and preferences of their children.

Family members are welcomed into the program and allowed to observe and participate in the activities.

Parents have opportunities to improve their educational and/or parenting skills.

Information about each child’s progress is routinely shared with parents.

Parents have opportunities to contribute to the policies and program of the preschool. They also actively contribute to the educational goals of their children.

The family’s home culture and language are respected, appreciated, and incorporated into all communications. The program understands the values, beliefs and customs of the families in order to design meaningful curricula.

All families are viewed as having strengths. The strong bond of care between parents and children is supported.

Critical for teachers, curriculum, and classrooms

Teachers have, at a minimum, a four-year college degree and specific training in early childhood education. They have a deep understanding of child development, teaching methods, and curriculum, allowing them to skillfully promote children’s social and cognitive development.

Teachers have frequent, meaningful interactions with children. They frequently engage children in meaningful conversation, expand their knowledge and vocabulary, use open-ended questioning, and encourage problem-solving skills.

Teachers teach important concepts such as mathematics and early literacy through projects, everyday experiences, collaborative activities, and active curriculum.

Teachers regularly assess each child’s progress and make adjustments as necessary. They carefully document the emerging abilities of each child and plan activities that promote increased achievement. They also collaborate with other staff and parents about the meaning of the assessments.

Teachers refer children who may have special learning needs for comprehensive evaluation and diagnosis.

Teachers are paid a professional salary with benefits. All staff are compensated according to their professional preparation, experience, and specialized skills. Career advancement opportunities are available.

Teachers and other staff are provided with ongoing professional development. There is active supervision, mentoring and feedback for all staff. There is a climate of trust, respect and cooperation among all the employees.

Teachers communicate respect for the families and warmth for the children. They are knowledgeable about the languages and cultures of the children and families.

Teachers are able to have respectful, collaborative relationships with other staff, parents, and other professionals. Each classroom has at least one teacher and a second adult who work as a team throughout the day. Standards should reflect, at a minimum, the recommended ratios from the National Association of Education for Young Children for program accreditation. (One staff member to 10 children and group size of no more than 20 for children ages 3-5.)

Teachers use a curriculum with specified goals, approach toward learning, expected outcomes and assessment procedures. Teachers should be able to describe their curriculum, why it was chosen and what they are accomplishing with it.

Children have opportunities to learn in spacious, well-equipped classrooms that have a variety of age-appropriate materials including art, music, science, language, mathematics, puzzles, dramatic play and building materials.

Summary

Before setting policy, it’s important to review what research into early education has documented. We know:

- The quality of early education and care significantly influences academic and social development.

- Children who are at risk for school failure are more strongly influenced by the quality of preschool.

- The average quality of care is less than good.

- Many vulnerable children attend the lowest quality programs.

- Many children from middle-class families also attend preschool programs of mediocre quality.

Taken together, these findings should lead policy makers to a sense of urgency about the need to improve the quality of preschool education in the United States. Since preschool program quality includes both structural and process features, they must be addressed together to achieve quality improvements. Accordingly, the regulations governing child-care licensing, as well as the educational requirements for preschool programs, are included in these policy recommendations.

Policy recommendations

Develop state standards that address preschool teacher qualifications, group size, and class ratios, in addition to the process features of programs such as teacher-child interactions, learning opportunities, assessment procedures, daily routines, materials, classroom environment, and health and safety routines. One route to higher quality is to support national (National Association for the Education of Young Children) or state accreditation for all preschool programs.

Raise teacher salaries and benefits to the levels of comparably qualified K-12 teachers.

Develop valid measures of early educational quality that incorporate the recent research on early literacy, mathematical, scientific and social-emotional learning.

Provide continuous training and quality improvement efforts to all preschool teachers and programs.

Work together at federal, state, and local levels of government to establish a coordinated system of high-quality education and care for all 3- and 4-year-olds.

Espinosa, L.M. (Nov., 2002). High-Quality Preschool: Why We Need It and What it Looks Like [Policy Brief]. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/resources/policybriefs/1.pdf.