The discussion in class about the impact of rising sea levels on coastal communities was electric. Students passionately discussed the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina and debated whether cities situated below sea level would survive the threat of climate change. They eagerly supported their opinions with facts they had learned about flood prevention strategies used in Venice, Italy, and Holland.

Now the class is ready to write summary reports comparing coastal flood defense strategies used in the past and today. You’ve taught them how to develop a main idea, organize supporting ideas and facts into paragraphs, and add descriptive detail. So why is your class finding this writing assignment so difficult? Why are students who were so engaged and articulate during the discussion finding it so hard to write?

Young writers are often able to discuss content, take notes, or create semantic maps to prepare for writing. Translating this information into a cohesive organized text, however, is difficult for many of them. The texts they create may lack “writers’ voices” and often do not include the new vocabulary or concepts introduced in class. In the worst-case scenario, the students may have writer’s block.

Authoring with Video (AWV) enables students to get started writing in a medium they know and love: video. It is similar to writing text for a wordless picture book. The videos, like the pictures in a wordless book, serve as the trigger for an organized text. Finding their voices as writers is less of a challenge for students because they are comfortable with messages and visual images working together to communicate meaning. AWV encourages students to formally recognize this ability as a skill that has its roots in writing. It capitalizes on the sophisticated video-viewing and comprehension abilities of children and casts them as writers, publishers, and producers of content.

Motivate students

We know that students revise more and spend more time on task when they are engaged in a project that has an audience beyond their teacher. Students’ motivation to fully engage in writing and revising text is sparked by their desire to communicate with the reader and by their individual pride of authorship. We also know that students regularly watch short video clips on websites, cell phones, and other hand-held media devices, and teachers have been using more and more video clips from curriculum-focused websites in their lesson plans.

AWV builds on these factors by providing a video-based platform for writing. Students are given short digital video clips with no audio and are asked to create a text narration in response to a writing prompt or task. By using software that enters their text as open captions beneath the video, students can focus on the craft of writing and revising.

With some initial guidance, students intuitively understand how visual images can be made meaningful with narration. One easy example is the narrative sequence of a televised baseball game. We all learn far more from an announcer than just a description of the game. We hear about the statistics and health of each player, controversial information about their personal lives, and predictions of their performance in the upcoming season. Students are very comfortable discussing television programs and movies and consider it routine to critique what they see and hear. AWV provides young writers with a platform to extend this critical assessment to their own writing and that of their classmates. This approach encourages students to revise their work while paying attention to structure and organization and not just to low-level editing. Over and over, students tell us that AWV helps them to be more creative and to write more. Writing with video literally helps them see the need for more detail and elaboration in their texts.

All of these factors can increase student engagement with written language and increase the quantity of writing produced. AWV also has the added incentive of producing completed movies to share with classmates, friends, and family. The finished product looks professional and can be easily posted to a website or blog.

The technology

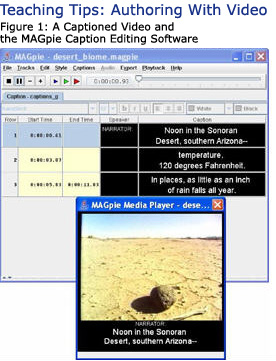

Students create captions for video and other images using MAGpie, free student- and teacher-friendly software developed by the WGBH National Center for Accessible Media. Unlike most digital movie software, MAGpie allows a user to easily produce and edit multiple lines of text. Students can author their narrative directly into the MAGpie interface, adding up to three lines of text in each caption, or they can use their word-processing program to author a narrative and then import it into MAGpie. Students can time and place the text transitions automatically or manually. As they create or edit captions, they can automatically preview the result and adjust the length and line breaks of their text as needed. The length of the final narrative is influenced by the length of the video clip provided and the amount of time that students choose to leave text on the screen. Step-by-step directions for downloading MAGpie and for using the software are on the AWV website . Figure 1 shows a screenshot of a captioned video and the MAGpie caption editing software.

Building on the writers' workshop approach

Students can often tell us more sophisticated things than they can write about. They write to get assignments done, not to affect readers. In order to do the latter, students need to write for readers they care about. They also need to be readers to understand how text can influence, convince, or entrance the reader. The work of Calkins (1986), Elbow (1981), Ray (2002), and many others suggested that good writing stems from hearing and reading good writing. Students familiar with good writing can more easily identify a style they like and want to emulate.

Instead of exposing children to good writing by listening to literature, AWV uses video to model effective writing. In Ray and Cleaveland’s (2004) approach to writing workshops, even the youngest authors “make stuff with writing” by having children write entire books. In their words,

One of the reasons students write only a sentence when asked to write is because the medium itself-often a journal page or a single piece of paper with lines at the bottom and space for a picture at the top-suggests this to them. The book medium is a whole different suggestion entirely, and it causes them to do a very different thing with writing.

Using video as an inspiration for writing offers upper elementary and middle school students a similar freedom that can begin for them an entirely new and creative relationship to text. Students are more motivated to envision the effect of their work on a viewer. The process makes explicit the role of good writing and revision in weaving multiple visual images into an interesting presentation or persuasive point of view.

As Calkins noted (1986), “Revision means just that: re-vision, seeing again. The words become like a lens (Murray), helping us see our emerging subjects and our developing meanings.” AWV supports this process of discovery as students realize that the video is only made meaningful by their text. Revising and rewriting their texts to make a compelling documentary encourages students to truly understand that the process of exploring ideas in text is iterative and not linear.

Teaching ideas

AWV can motivate students to apply knowledge in any content area to a writing task. Teachers can introduce students to the concept by showing them examples of videos with good writing. A wide range of writing styles can be found on public television programming. For example, many NOVA programs are available as streaming video on their website and can be watched without audio and with captions — just like the videos students will create using MAGpie. Consider using Storm That Drowned a City — a look at New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina — or Dying to Be Thin — a documentary about life-threatening eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia.

Also, hundreds of short, captioned, curriculum-matched clips are available on WGBH’s Teachers’ Domain , which can serve as a quick introduction to AWV. Watch the Teachers’ Domain video Unhinged without audio or captions and collect students’ ideas about the theme of the segment. The images in the video illustrate and supplement a narrative theme in the text that cannot be easily guessed by viewing the video alone. Chances are everyone will be surprised to find that the theme is evolutionary change in response to the pressure of finding food. This exercise drives home the power of text and the critical role of the writer.

To integrate AWV into any part of your curriculum, choose or make a video clip that corresponds to a theme or unit of study and develop one or more writing prompts or tasks. Consecutive AWV assignments can help measure writing gains while covering content objectives. Social studies teachers can use footage of current events or travel clips, or they can make a video using pictures and newspaper clippings. Language arts teachers at all levels will quickly see the possibilities for video-inspired creative writing assignments, including poems, first-person narratives, or journal entries. And there are many natural history and science video clips that lend themselves to the AWV process. For example, students can write text to accompany videos of science experiments, such as the popular Coca-Cola and Mentos explosion or the reliable baking soda and vinegar eruption. Your students should be able to craft a highly descriptive narration of the results. Have them share their finished videos in peer conference groups and critique one another’s ability to communicate both the lesson and the excitement of the experiment. You can also videotape your next class science experiment and then ask students to use the video to create multimedia lab reports.

A curriculum unit on endangered species could begin by showing a documentary of an endangered animal. A search on video sites for endangered animals will find many short downloadable videos of various animals that you can use with your class. The assignment could include a research component resulting in a traditional report or a persuasive piece that encourages increased protection of endangered species’ habitats. Students could also write a poem about the animal they choose, using the video as a backdrop.

The AWV approach is most effective when teachers identify, download, and distribute the clips for students to use in class. Using teacher-provided video clips forces students to focus on writing rather than the creative assembly of images. This also avoids the problems that arise when students search for video clips on their own. Some video sites may offer clips with inappropriate or overly complex content, or students may select videos with insufficient content or length to fit the assignment.

Students can, however, film their own content or create a slide show of images and then write a narrative to accompany them. Older students can assemble videos illustrating current events using images and photographs, or they can shoot footage of classroom activities or sporting events and then create commentary. Younger students, with the help of their families, could make a short video of a family pet or their neighborhood. This footage could be used in developing descriptive writing such as the use of adjectives or adverbials. Younger students will be challenged by writing text to accompany a 3-minute clip. Older students may be motivated to craft an entire narration for a 30-minute program.

Sources for video clips

Many schools subscribe to digital video library services that provide classrooms with access to video clips. There are also many education-focused websites that allow teachers to search for video clips by topic. Much of this content, however, is only offered as streaming media, although many sites are beginning to offer downloadable versions. AWV requires video clips that can be downloaded to your computer. Some downloadable video clips are on the AWV website. Other sources include Moving Image Archive , The Open Video Project , and The Library of Congress’s American Memory collection.

Keep in mind that using copyrighted works for nonprofit or educational purposes is generally considered to be fair use but policies and practices related to digital video are evolving. There are usually restrictions on the number of copies that can be made and on posting materials on the Web so make sure you review each distributor’s copyright information.

Strassman, B. K., and O’Connell, T. (2007). Authoring With Video. The Reading Teacher, 61(4), pp. 330-333